Jennifer Lortie is accustomed to facing obstacles to health care.

The 37-year-old assistive technology specialist for United Cerebral Palsy of Eastern Connecticut has cerebral palsy. As she describes it, her condition, which resulted in quadriplegia, means “pretty decent use of my left arm, very limited [use] of right arm, and no use of my legs.”

Lortie has worn glasses since she was a young girl; when she was smaller, her father would carry her up the steps of the eye doctor’s office, which wasn’t handicap accessible. When that became unfeasible, she had to find another eye doctor.

Jennifer Lortie/UCPEC Photo.

Jennifer Lortie, who has cerebral palsy, is accustomed to facing obstacles to health care.

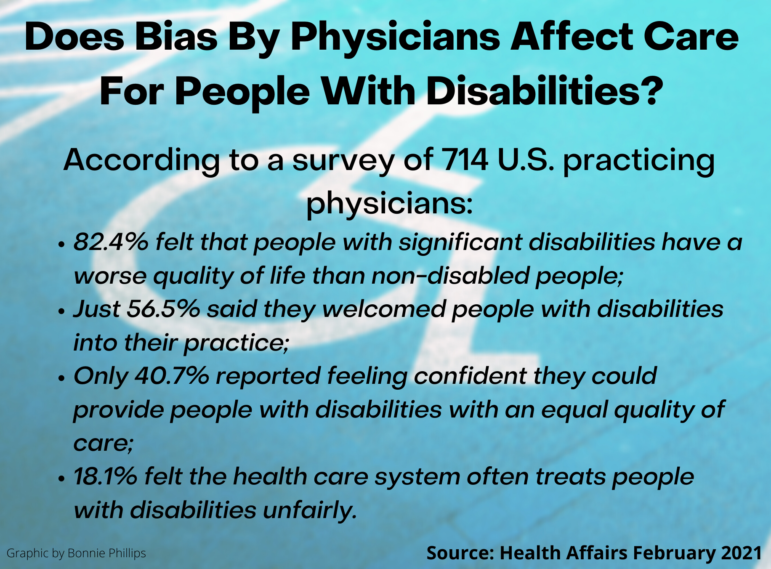

People with disabilities have long experienced inadequate access to health care. Now, a new study published in Health Affairs suggests that physicians’ attitudes and lack of knowledge about how to care for this demographic may be partly to blame for the health care disparities they endure.

Lack Of Preparedness

New research offers insight into why people with disabilities struggle to get adequate care. According to the Health Affairs survey, less than half of 714 physicians polled said they were “very confident” in their ability to provide care of equal quality to patients with disabilities. Just over half strongly agreed that they welcomed patients with disabilities into their practices. Almost 20 percent strongly agreed that the health care system often treats patients with disabilities unfairly. Advocates note that some segments of this demographic seem to struggle disproportionately.

Consider the experience of people who have Down syndrome. They are now living to an average age of 60, up from the mid-20s in the early ’80s, thanks to factors that include early medical interventions for heart defects, better overall care, and living at home as opposed to being institutionalized.

“The life expectancy [of people with Down syndrome] has grown immensely, but the health care system hasn’t caught up,” said Shanon McCormick, executive director of the Down Syndrome Association of Connecticut.

That could explain why Lisa Weisinger and her husband, both of whom are physicians, struggled to find satisfactory medical care for their 26-year-old son Jamie, who has Down syndrome, once he transitioned from the pediatric health care system. Eventually, they settled on the Down Syndrome Adult Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, a five-hour round trip from their home in Bloomfield.

Inclusive Medical Education

“Moving into the adult care world, I feel like we don’t do a good enough job in medical schools and residencies educating upcoming health care providers about individuals with developmental disabilities,” Weisinger said. An internist at St. Francis Hospital & Medical Center, she says she relishes her role in the hospital’s teaching clinic, which includes training medical students and residents on issues specific to individuals with disabilities.

The push to increase this type of training tends to be piecemeal rather than system-wide. Lacey Gowdy, a medical student at Quinnipiac University’s Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine, learned that patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) tend to get substandard care compared with other populations. Partnering with faculty mentor Traci Marquis-Eydman, MD, and Connecticut-based private service provider Oak Hill, Gowdy developed an elective course to help medical students better understand how to improve care for patients with disabilities. A $25,000 grant from the National Curriculum Initiative in Developmental Medicine allowed the course to continue past its launch date of August 2019.

The push to increase this type of training tends to be piecemeal rather than system-wide. Lacey Gowdy, a medical student at Quinnipiac University’s Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine, learned that patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) tend to get substandard care compared with other populations. Partnering with faculty mentor Traci Marquis-Eydman, MD, and Connecticut-based private service provider Oak Hill, Gowdy developed an elective course to help medical students better understand how to improve care for patients with disabilities. A $25,000 grant from the National Curriculum Initiative in Developmental Medicine allowed the course to continue past its launch date of August 2019.

Student and alumni feedback also has been a strong catalyst for change at the University of Connecticut School of Dental Medicine, said Steven M. Lepowsky, DDS, the school’s dean. In the early ’90s, approximately 16 hours of coursework was dedicated to instruction on caring for patients with disabilities. In 2020, it exceeded 60 hours. The goal, explained Lepowsky, is to ensure that all graduates have the same baseline competence and confidence to treat individuals with disabilities.

Some of that competence isn’t necessarily skill-based. Weisinger said, “It just takes that extra second to treat all patients like human beings, with the respect that they so rightly deserve.”

Advocating For Change

The pandemic has compounded health care-related challenges for people with disabilities. Some initiatives intended to minimize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have inadvertently excluded or otherwise negatively affected people with disabilities, explained Marissa Rivera, an advocate at Disability Rights Connecticut. Drive-through vaccine sites don’t work if you can’t drive, she said. Wearing a mask means people who normally read lips can’t. “There are so many layers we forget to think about,” Rivera said.

Stephen Byers

Rivera’s colleague, Stephen M. Byers, an attorney at Disability Rights Connecticut, described another pandemic-related regulation with unintended negative consequences for adults with disabilities. In June 2020, the state Department of Public Health (DPH) established restrictive visitation rules for hospitals and medical facilities, which meant that sometimes a caregiver or support person could not accompany a person with a disability into hospital rooms or the ER.

In response, Disability Rights Connecticut, along with more than 20 advocacy organizations and individuals, advocated for the DPH to lift the restrictions and allow caregivers and support staff to accompany patients.

Perhaps circumstances like these have imbued Lortie with patience as she waits—longer than originally anticipated—to receive the COVID-19 vaccine after Gov. Ned Lamont chose an age-based approach for vaccine eligibility, deprioritizing people with disabilities.

“I don’t have to go anywhere. But I’d like to go places,” said Lortie, who is working remotely rather than risking exposure to COVID-19 through the close contact that comes from taking two forms of public transportation to get to work: a van that is equipped to support people with disabilities and a bus.

But advocacy doesn’t always result in change. McCormick, of the Down syndrome association, said the state refused to reverse its decision to deprioritize the COVID-19 vaccine for individuals with disabilities even after being presented with new research showing that adults with Down syndrome were three times more likely to die from COVID-19 than the general adult population of the same age, gender and ethnicity.

“It’s been extremely frustrating,” McCormick said. “We have taken that information to people inside the administration. It’s clear. It’s documented. And it has just fallen on deaf ears.”

Thanks for covering this. The term “disability” goes further than most readers might assume. My child with Asperger’s Syndrome has had a difficult time finding medical care from sensitive providers. Aspies often have difficulty in describing their medical problems and talking comfortably with care givers, and, as many know, they often have trouble looking people in the eyes. One specialist to whom we were recommended called me and said that we were not welcome to come back because he and his nurse thought my son was frightening because he wouldn’t look the nurse in the eyes. Another doctor told me his nurse had complained about the same problem and that I needed to have a serious talk to my son. We were treated as if my son had done something wrong. He’s actually the sweetest kid in the world. Please consider doing some reporting on this aspect of medicine, and thanks for the article.

I wouldn’t recommend Dr Lisa Weisinger for anyone with disabilities. Speaking from personal experience, she doesn’t listen to or believe her patients or her patients’ other providers.