Stamford Hospital is treating most of its critically ill coronavirus patients with blood plasma from people who have recovered, after stunning turnarounds in several patients who were gravely ill.

“We started with only the sickest patients on respirators. Then we offered it to all of the patients on respirators, then all the patients in the ICU, and now all the COVID patients in the hospital on 40 percent oxygen, not with a ventilator,” said Dr. Paul Sachs, director of pulmonary medicine. “So far, there has been cautious enthusiasm.”

Contributed Photo.

Amy Harel of Fairfield donated her plasma at Norwalk Hospital, after recovering from COVID-19.

Plasma transfusions are gaining traction at other hospitals throughout Connecticut and nationally as well, as doctors wait for a breakthrough treatment. Nuvance Health, which includes Danbury and Norwalk hospitals, reports more than 200 patients system-wide treated with plasma so far. The network opened its COVID-19 plasma donation centers recently and already counts about 1,750 donors in its database.

Trinity Health of New England, which includes Saint Mary’s Hospital in Waterbury and Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center in Hartford, is running a plasma transfusion trial. Hartford HealthCare and Yale New Haven Health are transfusing patients who fit the protocol established in a national plasma transfusion clinical trial overseen by The Mayo Clinic, which began last month. As of Monday, Hartford HealthCare has transfused more than 215 patients across its network.

As the number of survivors grows, more plasma will become available, and the number of transfusions will increase, said Dr. Mahalia S. Desruisseaux, an infectious disease expert at Yale.

While it’s too early to cite data from trials, “there’s clearly a benefit” to the transfusions, she said. “Anecdotally, the earlier you administer it, the better you do. Are you giving it to someone who’s going to get better anyway? We don’t know that yet.”

In Stamford, Henry Woerz, 76, of New Canaan, continues to recover after he received the first plasma transfusion in Connecticut on April 10. Before the procedure, he had spent 21 days on a ventilator, with his condition going from bad to worse. The hospital had called his sons Craig, Jeff and Jason “basically, to come in to say goodbye,” Craig Woerz recalled.

The Woerz brothers learned about plasma transfusions from their father’s primary doctor, Remi Rosenberg, and they recruited potential donors online. Then the brothers and Rosenberg appealed to Stamford Hospital to try a transfusion. Craig Woerz said he “appreciated the hospital’s collaborative spirit. There was never a push out of the hospital, and we never gave up.”

Stamford Hospital is one of the few independent hospitals left in Connecticut. “Because we are an independent, medium-sized hospital, we are maybe more nimble,” Sachs said. He and his team wrote up a protocol for a transfusion trial and submitted it to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Woerz became the first recipient.

“We were overwhelmed with patients coming in and had absolutely no treatment. We were just throwing things off the wall to see if it stuck,” Sachs said. “The first rule is do no harm, and we hadn’t heard of any adverse effects with convalescent plasma. This appeared to be an experimental, compassionate, possibly plausible remedy with a good safety record.”

When a virus or infection strikes, the body’s immune system makes cells and proteins to fight it. In many patients who have recovered from COVID-19, their plasma remains rich with these antibodies for at least a month afterward. A transfusion can put the little antibody soldiers to work in another critically ill patient. For more than a century, doctors have used convalescent blood plasma to combat diseases, from the Spanish flu to measles to polio to Ebola. Following the COVID-19 outbreak in China, two small studies showed that convalescent plasma was used there to treat 15 patients who ultimately survived.

Carl Jordan Castro Photo.

Dr. Paul Sachs and his team wrote up a protocol for a transfusion trial and submitted it to the FDA.

Woerz received two small baggies of antibodies over five hours. Two units of plasma are now the standard protocol at Stamford Hospital for all appropriate COVID-19 patients. (The Mayo Clinic trial recently changed its national protocol to one or two units, so Stamford has joined that trial as well.)

“He had such a dramatic change the day after he got the plasma, and within a week he was off the respirator with high levels of oxygen,” Sachs said. “The rate at which he survived and the time point at which he pivoted his progression are hard to ignore, but I would emphasize this is not a randomized trial, and it is difficult to impossible to make firm conclusions.”

Since the plasma transfusions began in Stamford, about 40% of patients have been extubated, 45% remain on ventilators and 15% have died.

From Survivor To Donor

Amy Harel, an orthodontist in Fairfield who survived COVID-19, said she regrets not bringing her father to a Connecticut hospital for treatment. On a trip to Disney World in March, a stomach bug kept her father, Ron Panzok, in the family’s suite at the hotel. Days after they returned, Panzok headed to the emergency room near his Long Island, N.Y., home, and learned he had COVID-19. Everything deteriorated from there. The entire family got COVID-19: both Harels, their 18-month-old daughter, and the aunt and uncle who drove everyone to the airport.

Panzok, 66, had been “a healthy, hardworking man who biked and had a physical job,” Harel said. Now he was sedated with paralytics, spending week after week on a ventilator, resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome and complete kidney failure. “The hospital was so insane they called it the Wild West. All day every day, I spent researching treatments and trying to get someone to pay attention to my dad.”

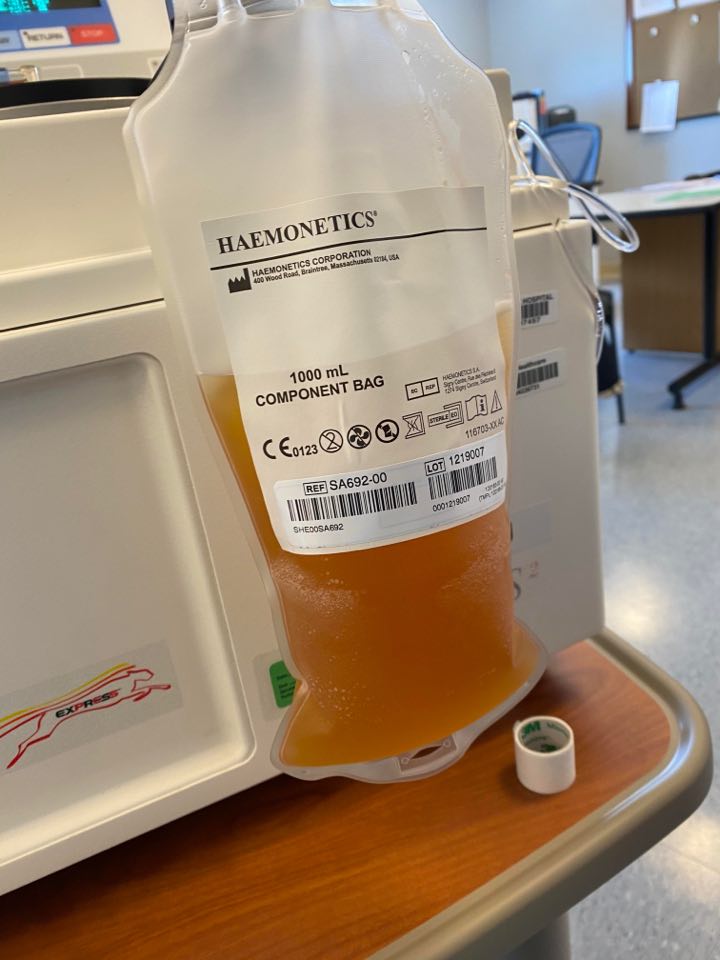

Contributed Photo.

Amy Harel’s donated plasma.

No sooner did Harel connect with one doctor, she’d discover her father had been transferred to a different ICU. Finally, she tracked down the ICU chief. She pleaded with him to try a plasma transfusion. “Every time I asked, he said, ‘We’re waiting [for approval].’ It was a nightmare.”

Eventually, the hospital sidestepped administrative red tape and received emergency approval from the FDA for Panzok’s transfusion. But the wait took its toll. Though he is finally breathing on his own, her father needs dialysis and falls asleep after saying a sentence. “He’s alive, thank God. It’s a miracle,” his daughter said, “though now I’m worried about his quality of life.” Panzok will need six to nine months of rehabilitation.

Harel is convinced that recovered plasma saved her father, and she hopes to save others with her plasma. When she received a call from the Fairfield health department, which has been checking up on her regularly after her positive diagnosis, they encouraged her to donate at Norwalk Hospital’s new plasma center.

Harel spent two hours there recently, watching her blood cycle through a machine that separated her red and white blood cells, saline, and plasma, spinning out the yellowish plasma, and returning the rest of the blood to her. “Seeing the plasma going into the bag was shocking to me because I didn’t expect to see it. But I donated because it helped my dad, and I want to help others,” she said.

So, if this is considered to be a realistic treatment for COVID-19, where can someone go to be tested for the antibodies? I have been fortunate and have not experienced any severe symptoms that would suggest I’ve been exposed. But then, my body seems to have a very strong immune system that facilitates speedy recovery and/or healing. If I had been exposed and did develop the antibodies, how would I know? I would like to be tested because IF my body has what it takes, I would donate in a heartbeat. Repeatedly.

Where can a healthy person go to be tested WITHOUT having to deal with the medical bureaucracy commonly experienced?