One thing that everyone agrees on: the Quinnipiac River is a lot healthier than it used to be.

“It really was a cesspool,” said Mary Mushinsky, a state legislator from Wallingford and former science educator for the Quinnipiac River Watershed Association. Mushinsky remembers a river full of old tires, shopping carts and untreated sewage. “In the old days parents would warn their children to stay away from the river,” she said. “It’s come back in a big way.”

Not far enough, though.

State environmentalists have now taken aim at phosphorous. The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) released new limits on phosphorous in 2011, triggering an uproar in some towns along the river that will have to spend millions to meet the new mandates.

Phosphorous, unlike the PCBs, heavy metals and sewage that have historically contaminated the Quinnipiac, is not a public health threat, although it occasionally spurs the growth of toxin-producing blue-green algae.

So why is the state pouring so much time and energy into cleaning it up?

“It’s been an evolution,” said Betsey Wingfield, DEEP’s Bureau Chief, Water Protection and Land Re-use. “First we got the solids out. Then we worked on dissolved oxygen and bacteria and heavy metals. Then it was nitrogen, and now it’s phosphorous.”

DEEP environmental analyst Mary Becker insists that the new focus on phosphorous doesn’t mean that the state is neglecting Quinnipiac’s other pollution problems. While industrial chemicals remain an issue, tougher regulations, closing factories and remediation have reduced their levels.

Copper levels, for instance, which serve as a marker of industrial processes, have decreased from an average of 9.6 parts per billion (PPB) in 1982 to an average 3.18 PPB in 2011, according to the United States Geological Survey. Companies, such as Solvents Recovery Services of New England in Southington, which sat 500 feet from the Quinnipiac and discharged lead, mercury, PCBs and other toxic chemicals into the river, have shut down.

Toxins remain in the soil and sediment – some PCBs, especially, do not decompose easily and can linger for decades – but state and federal programs are slowly cleaning them up.

“There are still remaining remediation sites along the Quinnipiac, but we have established programs to handle the toxics,” said Becker, who says that these cleanup programs will continue as before, despite the new focus on phosphorous. “If we want a healthy river, we have to focus on nutrients as well.”

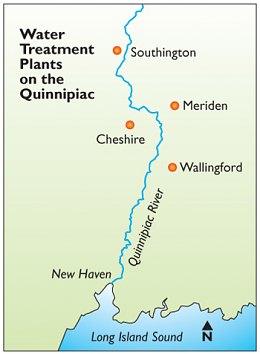

One of the key differences between historical pollutants on the Quinnipiac and phosphorous is their source. Historically, toxins leaked into the river from hundreds specific “point” sources and more diffuse “non-point” sources alike. Phosphorous is different. According to DEEP, 93.5 percent of the river’s phosphorus comes from just four sources: water treatment plants in Southington, Cheshire, Meriden and Wallingford.

While other sources, such as fertilizer runoff, likely contribute to the Quinnipiac’s phosphorous burden as well, it’s clear that the water treatment plants pack the biggest punch, so the new rules hit them hard. Each of the four facilities must reduce their daily phosphorous discharge to .2 PPM per day, except for Meriden, which must get down to .1 PPM per day.

“We want to be good stewards of the Quinnipiac,” said Southington Town Manager Garry Brumback. “But to go from 2.8 parts per million of phosphorous to .2 parts per million is a $18 million proposition, and we don’t even know if it will fix the problem.”

DEEP scientists argue that their science is sound. Plants need phosphorous to grow, but excess causes an overgrowth of plants and algae. By late summer, algae blooms cover the surface of the Quinnipiac like a blanket, making it impossible to canoe or kayak through certain parts of the river. In the fall, when the algae die and sink to the bottom, they consume dissolved oxygen in the water, making it unhealthy for fish, frogs and other river species.

According to DEEP calculations, when a freshwater river reaches an “enrichment factor” of 8.4 – that’s 8.4 times the natural level of phosphorous – algae blooms are triggered. The Quinnipiac, at about 38 miles long, is one of the worst affected rivers in the state, with an enrichment factor of 31 to 68, depending on sampling time and location. Getting the Quinnipiac to 8.4 will require a four-to-eightfold reduction in phosphorous.

Meeting the new limits will be expensive. Reducing phosphorous to .3 or .4 PPM can usually be done with lower-cost chemical or biological methods. But getting it lower than that requires large, expensive filters usually housed in a separate building. For the town of Southington, for instance, lowering phosphorous output to .7 PPM would cost about $50,000, according to town manager Brumback, but getting down to the required .2 PPM would cost an estimated $18 million, leading to a 20-23 percent rate increase for consumers.

“Below .2 is where it gets into major money,” said Frank Russo, superintendent at the Meriden Water Pollution Control Facility. Russo noted that adding phosphorous filters will cost his town $13 million, leading to a 22 percent rate increase for customers. This would be an especially painful financial burden for Meriden, which just completed a full plant upgrade in 2010, leading to a 27 percent rate increase for customers.

“It’s not like the phosphorous in the water is a health hazard or anything,” said Russo, who noted that their new system has already dropped phosphorous levels in the plant’s effluent by 70 percent. “Right by the outfall pipe we have 24-inch trout swimming around, the water’s so clear.”

Russo noted that in May, the state passed a law limiting the amount of phosphorous fertilizer that homeowners can use on their lawns. He and others argue that these new regulations, along with some water treatment control of phosphorous, might fix the river.

Scientists and advocates say this reasoning is faulty, however.

“Partway isn’t good enough,” said Mushinsky. “If the goal is to stop the algae blooms, then we need to respect the science. And what the science says is that the blooms are triggered by an enrichment factor of 8.4. There’s no reason to think that the science is not accurate.”

The new rules will be imposed when facilities renew their water permits, though the state will offer them extra time to comply with the new phosphorous rules. Currently the permits for all four plants are awaiting renewal. The affected municipalities have formed a coalition to oppose the new phosphorus limits.

DEEP’s Wingfield is sympathetic to the towns’ plight, but noted that the Connecticut limits are generally less strict than those imposed by the EPA in states like Massachusetts and New Hampshire. She also pointed out that the sewage treatment plants could get financial assistance through the Connecticut Clean Water Fund. In fact, the town of Cheshire dropped out of the coalition after receiving Clean Water Fund support for their upcoming $32 million treatment plant upgrade, $7 million of which will be for phosphorous reduction.

Even with the new limits, the Quinnipiac has a long way to go before it’s truly clean.

“It’s not like you get the phosphorous turned off and it’ll be perfect. It’s a long-term project,” said Becker, who calls the Quinnipiac watershed a “challenging” one.

“Someday it would be nice to think about kids going down to the Quinnipiac for fishing and boating, and not being grossed out by algae coming after them like the blob from the deep,” she said.

Indeed, in the 1890s, tourists traveled from across the region to swim at Dossin Beach and enjoy the park at Hanover Pond.

“I’m probably being idealistic,” said Becker, “but I’d like to think that people might be able to use the river in that way again.”

Sounds like a great initiative. The cleanup may be expensive but totally worthwhile.