At the corner of Shelton Avenue and Hazel Street in Newhallville sits a green space, the Learning Corridor—a hub for educating young children and connecting families to healthy living. The Farmington Canal Heritage Trail runs through the garden, where children can stop by and browse books from a box and adults can take a spin on a bike.

Once known in the neighborhood as the “mud hole,” a crime spot for “drug trafficking and all kinds of stuff,” the Learning Corridor is now a place where neighborhood residents gather to take care of their health and well-being, said Doreen Abubakar, founder and volunteer director of the Community Placemaking and Engagement Network (CPEN).

“We held a six-month in-house training about diabetes,” Abubakar said. “My sister who had diabetes brought down her blood sugar to pre-diabetic levels after she did the training.” The participants learned the importance of exercise to manage their diabetes, and residents joined the national walking club movement Girl Trek. Last year, Abubakar and her team planted native perennials and shrubs, and this year received a grant for the nursery from the Audubon Society.

But those who live in and work to improve Newhallville—a neighborhood long associated with poverty, violence, and trauma—know more work needs to be done.

Newhallville is one of thousands of neighborhoods in the U.S. where childhood opportunity is ranked “Very Low”—a designation that impacts their health, well-being and even lifespan—new neighborhood-level data from Brandeis University show.

“All our data show that two children born just a few miles apart [in New Haven, Bridgeport, and Hartford metros] experience vastly different neighborhood conditions in childhood and have a six or more year gap in life expectancy simply based on where they were born,” said Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, director of the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy at the Heller School at Brandeis. In fact, Newhallville ranks “Very Low” for overall child opportunity across 29 indicators, including access to green spaces, walkability, and access to healthy foods.

Residents are all too aware of the disparities cited in the study. “Just drive up four blocks or so and there are millionaires,” said Rhonda Nelson Sheffield, a 56-year-old resident and manufacturing worker who has lived in the neighborhood her entire life.

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Tammy R. Chapman in her garden. In addition to vegetables she grows medicinal herbs and plants to attract pollinators.

Newhallville is an area that has been disadvantaged since the 1960s and has become “even more economically disadvantaged over time, as evidenced by the fact that it has become poorer relative to other areas—even if its absolute poverty rates or income levels have not changed or have even improved at times,” said Mark Abraham, executive director at DataHaven.

According to a 2019 DataHaven report, the average household in Newhallville earned $33,113 annually, compared with $73,781 statewide. Nearly 4,054 residents were living in households with incomes less than twice the federal poverty level. In Newhallville and nearby Dixwell combined, as much as 83% of children under 18 were considered low income, the data from 2017 show.

One mile in radius, Newhallville is situated within a metro that offers vastly different opportunities to children living just a few blocks apart from each other. The Brandeis researchers refer to this difference as the Child Opportunity Gap.

In the New Haven metro area, the Child Opportunity Gap is 90 points—the poorest scoring neighborhood had a score of 6, while the highest-scoring neighborhood scored 96.

Barriers To Healthy Food

Across the country, cost and distance are barriers to healthy food. In Newhallville, 30% of households do not possess a vehicle, compared with 9% of households statewide, according to DataHaven.

“We live in a food desert,” said Devin Avshalom-Smith, whose grandparents migrated to Newhallville from North Carolina nearly 65 years ago to find work. Avshalom-Smith is working with Gather New Haven and the New England Brewing Company to secure funding for the Big Starr Street Garden and Little Starr Street Garden and has plans to distribute fresh produce to Newhallville residents. He is also circulating petitions to qualify to run in a Democratic primary for alder in the 20th Ward.

“There’s nothing here except the corner store,” Sheffield said.

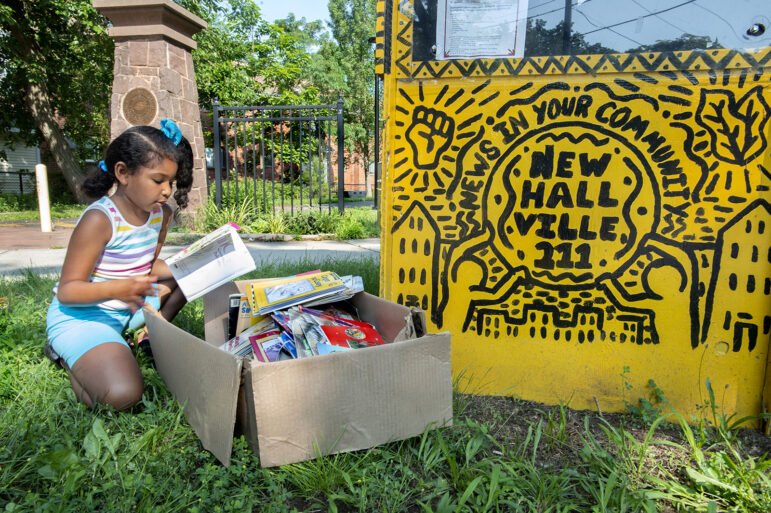

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Madison Roscoe, 6, of New Haven checks out books dropped off at the Learning Corridor.

Sheffield’s friend Jeanette Sykes, founder of the nonprofit Perfect Blend, which helps students prepare for college, also grew up in Newhallville. “We should get fresh vegetables and not have to go all the way to Hamden or the downtown New Haven Stop & Shop,” Sykes said. “It’s expensive, too. The local stores mostly carry canned things that have more sodium.”

Despite the challenges, Tammy Chapman, founder of Newhallville Community Matters, is proud to be a resident of a neighborhood that has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1988. The neighborhood was once home to the Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

“There’s deep roots here,” Chapman said. “There’s generational families. And so, there’s no shame. You’re having a tough time, you can call the neighbor down the street who may have a connection to the food pantry.”

During the height of the pandemic, neighbors quickly identified people who they thought might be in need. “At some point, we were all panicking because there was very little flour, very little milk and these types of items,” Chapman said. “But if people had extra—and the churches were wide open distributing food bags—those places made it a little bit easier. I found people working together really, really well. That’s the beauty of the community that I represent.”

Residents also began planting vegetables on porches in pots or in side and back gardens. Chapman grows tomatoes, green beans, and lettuce and is frequently bagging extra produce for neighbors.

Neighborhood Investments

Over the last few years, several community groups have made investments to help improve the quality of life in Newhallville.

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Alex Martinez helps Salamatu Mohammed get started riding one of the bicycles provided for use by the Learning Corridor. Martinez is a Newhallville resident and works for the Community Placement Engagement Network. (CPEN )

The Beulah Heights Social Integration Program provides grants of up to $15,000 for rent and utility assistance for residents in the Newhallville, Dixwell and Fair Haven neighborhoods. Only 30% of Newhallville residents own homes, Brandeis data show. “Investors are buying houses here, and they are pricing us out,” said Sheffield, who rents an apartment. Her parents own their house across the street from where she lives.

ConnCAT is responding to the lack of access to capital with a plan to disburse $600,000 to families in Newhallville and Dixwell for basic needs and to create Black-owned businesses.

The Hispanic Health Council’s office on Sherman Avenue provides support for mental health and substance use disorders. Now, caseworkers are addressing rising anxiety levels from pandemic isolation. “A lot of our families have issues with depression and anxiety,” said Carlos Rivera, director of Behavioral Health Services. “On top of it, they’re afraid to go outside [because they are unvaccinated due to fear of vaccination]. They lock themselves in.”

Now, Newhallville is attracting an influx of people. The neighborhood is “becoming very mixed,” Chapman said. “Especially last year, people from New York and New Jersey were coming into smaller areas. We’re seeing students from Albertus Magnus, Quinnipiac, Southern and Yale. People are coming in because they feel and see something that is, I would say, unique.”

C-HIT intern Ishan Rangarajan, a student of math and economics at Princeton University, compiled data for this story.