On a sunny, cool day as fall gave way to winter, a team of biologists and technicians dragged white cloths through the underbrush at Lord Creek Farm in Lyme. They were looking for blacklegged ticks, which carry Lyme disease and four other deadly illnesses.

As ticks attached to the cloth, the team counted them and put them in jars for further study at their lab at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven. Japanese barberry bushes grew thickly beneath the trees at this private horse farm that for years has cooperated with Lyme disease researchers.

As the group dragged cloths, they noticed ticks on each other’s pant legs and coats, and began to pick them off. This seemed to prove what the team leaders, biologists Scott C. Williams and Megan Linske, have found in one of their previous studies: More ticks thrive beneath tangles of Japanese barberry, with its year-round leaves and thorns, than in landscapes without barberry.

About an hour earlier, surveying The Preserve—public land in Old Saybrook—the team had found just one tick. That forest has no visible barberry and few invasive plants.

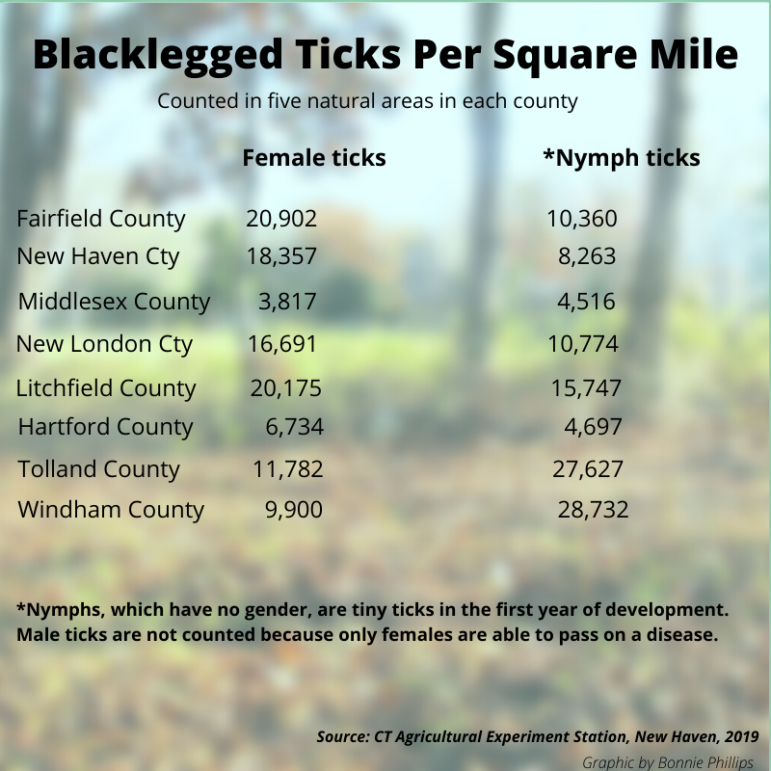

Throughout 2019, the scientists sampled 40 forested places in all corners of Connecticut. This study aims to calculate which landscapes attract ticks and which don’t. The early results, which they made public for the first time last week, reveal astonishing densities of the ticks that carry Lyme and four other diseases. In Fairfield and Litchfield counties, scientists found more than 20,000 adult biting ticks per square mile. The densities were almost as high in New Haven and New London counties, with more than 18,000 and almost 17,000 ticks per square mile respectively.

Their tick samples also reveal the grim truth of how Lyme disease increases in ticks if they survive into adulthood. Only 15% of nymphs (young ticks) that the team collected carry Lyme, but within a year of feeding on mice that carry the disease, almost half adult ticks carry Lyme disease. Nymphs are a threat to humans because they are so small and their bites often go undetected.

Their tick samples also reveal the grim truth of how Lyme disease increases in ticks if they survive into adulthood. Only 15% of nymphs (young ticks) that the team collected carry Lyme, but within a year of feeding on mice that carry the disease, almost half adult ticks carry Lyme disease. Nymphs are a threat to humans because they are so small and their bites often go undetected.

The town of Lyme, of course, is like ground zero for Lyme disease, which was discovered there in the 1970s. The blacklegged ticks carry Lyme disease and four other deadly diseases: anaplasmosis, borrelia miyamotoi disease, babesiosis, and Powassan virus.

Williams said infection with Powassan in 2019 was low, just five cases in the state. But Powassan is a dangerous illness. Former U.S. Sen. Kay Hagen of North Carolina died of Powassan in October. Congress is considering a bill called the Kay Hagan Tick Act for tickborne disease research funding.

Lyme disease has become a national health crisis. It is caused by a microscopic spirochete that enters the bloodstream and hides in the tissues. In 2018, Connecticut ranked fourth in the nation for Lyme cases, with 1,859 reported new cases that year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said. But the actual cases are probably 10 times that number (or roughly 18,500), the CDC reported.

Nationwide, the CDC estimates 300,000 cases a year. In 2015, a study at Johns Hopkins University estimated that as many as 440,000 new cases of Lyme are diagnosed each year, costing the health system $712 million to $1.3 billion a year.

The State’s Altered Forests

Lyme disease has been around for millennia. It evolved into ticks that bite humans because the landscape now favors those ticks.

Christine Woodside Photo.

Biologist Scott Williams holds one of the tiny blacklegged ticks before putting it in a jar.

Since about 1900 Connecticut has changed from mostly farmland into a land of small forest patches interrupted by grassy areas. The white-tailed deer and white-footed mouse, two important animals whose blood ticks need to survive, all thrive here.

Although 60% of Connecticut is forest, much of that forested land is cut up into narrow segments. Such fragmented woods create lots of places at the edge of woods where sunlight encourages the shrubs that deer eat—and where ticks survive.

At a forum on urban forests three months ago, Williams told a group of scientists and amateurs that deer have created landscapes that favor ticks. They eat native plants and leave behind invasive plants that tend to shelter the ticks through the winters.

Both scientists said that the time has come to understand why these forests harbor ticks. At the same forum, Linske called the life cycle of the blacklegged tick “quite the process.” It goes like this: In the ticks’ first year, as nymphs, they feed on mice. Not all ticks are infected, but those that are pass the diseases on to the mice. The mice then pass on those diseases to other uninfected ticks that bite them.

After feeding, the ticks drop off the mice. They then spend another season feeding on other animals, especially deer. Thousands of ticks can be found feeding on a single deer.

Unlike mice, deer can’t spread diseases ticks carry to other ticks from their bodies. The deer’s most important roles in spreading Lyme is they provide blood meals to ticks just before they lay their eggs.

The blacklegged tick has been called the “deer tick.” It would be truer to call Connecticut a deer landscape. Williams said deer don’t pass on Lyme disease the way mice do, but deer are pivotal to keeping ticks healthy so they can lay their eggs. Deer also disperse seeds of some plants that encourage ticks.

“This is an important study, and the hope is to have it continue every year,” Williams said last week, “but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention only gave us enough funding for this first year.” He said they need state or federal funding to continue sampling.

Their work could better define areas where people are more likely to contract dangerous tickborne diseases. And it will help Connecticut residents understand better how to avoid ticks.

TIPS

Japanese barberry.

• Homeowners should cut back Japanese barberry bushes on their property every five years.

• Change clothing after coming inside. Scientists often put their clothes right into a dryer.

• If spending extended time outdoors, people might prefer protective clothing treated with insecticide, available through outdoor outfitters.

• People can avoid tick bites by learning how to check themselves for ticks. Click here for information.

To view the locations where the team collected ticks click here.

As a resident of Unionville, I have had numerous tick bites just from gardening in my own yard. I live on a wooded cul de sac and am surrounded by the Farmington Forest and permanent open space owned by the town. I am living with residual Lyme disease and 2 other tick borne diseases. You may be able to collect sample ticks here as we have abundant wild life all year round, who carry them through our woods. White tail deer and black bear abound! Others seen regularly include bobcat, raccoons, field mice and rabbits. I live adjacent to a spring fed pond so these animals all visit for drinking and bathing. It is a special spot and I love living here……but the ticks are everywhere.

The only way to make a serious dent in tick populations is sterilization therapy. Look up the company Oxitec. There is also a tick robot invented by a VMI prof that was cited in The New Yorker some years ago.