The death rate from heart disease plummeted nationally over several decades for all racial and ethnic groups, but the rate of decline has slowed slightly and African Americans and low-income individuals are still at a higher risk of developing the disease and dying from it, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

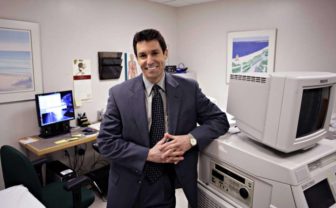

Carl Jordan Castro Photo

Dr. Edward Shuster standing in front of a stress test machine.

The report isn’t surprising to Dr. Edward Schuster, medical director, Stamford Health Cardiac Rehabilitation Program. “In the United States, there’s a lot of talk about income disparity, which is a political hotcake,” Schuster said. “But what we are seeing is a life expectancy disparity. According to a recent Journal of American Medical Association, if you’re a man in the top 1 percent of income, you can expect to live 13 years longer than someone in the 1 percent at the bottom.”

Heart disease is largely preventable by maintaining a balanced diet, a healthy weight and moderate exercise, with only 20 percent of cases involving genetics, said Dr. David L. Katz, who heads the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center, which works with communities to develop programs to control chronic diseases.

New Haven Register Photo

Dr. David L. Katz

But significant groups in lower income and urban areas don’t—or can’t—act on the message, Katz said.

“Your zip code is a better predictor of your health than your genetic code,” Katz said. “It all depends on what your neighborhood is like. Do you have access to fruit and vegetables? Do you fear walking your streets? Where you live is massively more important than your genetics.”

Schuster agreed, and said heart disease clearly is a zip code issue with more —and younger—adults facing higher rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity in lower-income communities. “In the poorer zip codes, within a block of each school, kids can walk to get junk food,” Schuster said. “It really is a cultural crisis and I’m not sure it can be fixed.”

Nationally the death rate for non-Hispanic blacks has dropped from 337.4 per 100,000 U.S. residents in 1999 to 208 per 100,000 in 2017, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. But non-Hispanic blacks are still twice as likely to die of heart disease than whites, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders or Asians, the report said.

Connecticut is following the national trend, according to figures provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 2005, 7,650 Connecticut residents died of heart disease, translating into a death rate of 180.7 per 100,000. In 2014, 7,018 Connecticut residents died of heart disease, a death rate of 145.6 per 100,000.

The heart disease death rate in Connecticut has remained fairly steady since 2015, with the annual number of deaths hovering between 7,000 and 7,200. Nationally the death rate from heart disease dropped from 216.8 deaths per 100,000 U.S. residents in 2005 to 165 deaths per 100,000 U.S. residents in 2017.

Despite the decreases, African Americans and low-income individuals in Connecticut remain at a higher risk for obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes, all chronic illnesses connected to heart disease, according to the 2017 Connecticut Cardiovascular Disease Statistics Report by the state Department of Public Health (DPH).

DPH received a $4.3 million grant to fund programs for low-income urban residents aimed at identifying and reducing chronic health problems linked to heart disease, said Elizabeth Conklin, spokeswoman for the agency. About 70 percent of the grant is spent on programming, the remainder pays DPH personnel.

But it’s a struggle to reach low-income families who are wrestling with issues such as housing and transportation while inexpensive high-fat and high-sodium foods are easily available.

“Diet and exercise are the least of your priorities if you spend two hours every day on the bus to get to work,” said Lisa McCooey, the DPH’s cancer program director and acting director of chronic disease.

Dr. Harlan Krumholz

It is unclear if the numbers are actually showing that the death rate from heart disease has stalled, according to Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a Yale University cardiologist and researcher, since it’s impossible to tell whether or not cardiac arrests from the opioid epidemic are being included in heart disease death statistics, he said.

But it is evident that people in lower income brackets don’t have the same resources to take walks in safe neighborhoods, a quality array of fruits and vegetables close by and access to good health care, which includes regular blood pressure screenings, Krumholz said.

“It is economic,” Krumholz said. “Many people live in a food desert where food is cheap but not nutritional. There are no opportunities to exercise and no access to health care.”

Advances in medicine and technology drove the sizeable decreases in deaths over the past two decades, according to Katz. Now it will likely be up to lifestyle changes to drive any further decreases, he said.

The Yale-Griffin prevention center is testing out a program that encourages doctors to issue prescriptions for fruits and vegetables that can be purchased for a low cost at farmer’s markets. The patient’s employer pays a portion of the tab, “because it’s cheaper than a bypass,” Katz said.