Getting to the hospital quickly after suffering a stroke improves your chances of survival, but in Connecticut there are areas where access to the top level of stroke care is limited, health experts say.

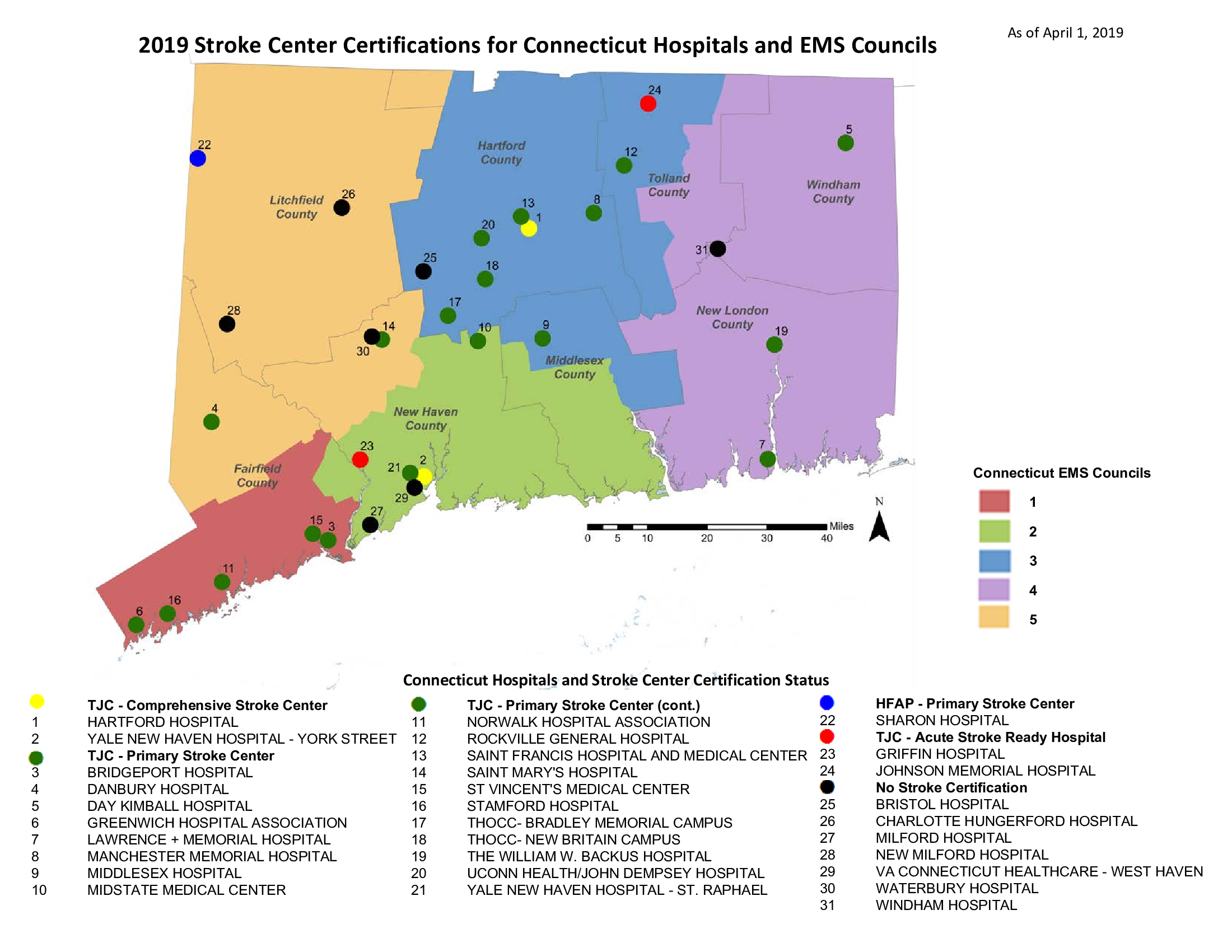

Two hospitals, Yale New Haven Hospital’s main campus and Hartford Hospital, are nationally certified as Comprehensive Stroke Care Centers, providing the highest level of stroke care available, which includes 24-hour access to neurological practitioners and the ability to perform complex endovascular therapies, including thrombectomies and endovascular coiling of an aneurysm, among other surgeries.

Yale and Hartford hospitals are two of only 178 certified nationally as comprehensive stroke centers, according to The Joint Commission, which certifies hospitals.

But when time is critical, traveling to New Haven or Hartford can be a risky commute from the northwestern and northeastern parts and other parts of the state, where hospitals certified in stroke care are sparse.

In all, the state has 23 hospitals that are certified in some level of stroke care, up from 16 in 2013.

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Dr. Joseph L. Schindler heads Yale’s Acute Stroke and TeleStroke Services.

Nineteen hospitals—including Norwalk Hospital, Stamford Hospital, St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Bridgeport, Bridgeport Hospital, Danbury Hospital, Greenwich Hospital, Middlesex Hospital in Middletown —are certified as primary stroke centers, and are equipped to do brain scans, administer clot-busting drugs (IV-tPA) and provide neurosurgical services.

In addition to Yale and Hartford Hospital, UConn Health John Dempsey Hospital in Farmington, St. Francis Hospital & Medical Center in Hartford, Stamford Hospital, Danbury Hospital are among the facilities that perform thrombectomies, according to a member of the state’s Stroke Advisory Committee. A complete list was not available. The Joint Commission does not require primary stroke centers to perform thrombectomies.

Griffin Hospital in Derby and Johnson Memorial Hospital in Stafford Springs are certified as acute stroke-ready hospitals, providing basic care, including administering drugs to break up a clot and evaluating whether a patient needs to be transferred to a primary or comprehensive stroke center.

Seven facilities — Charlotte Hungerford Hospital in Torrington, Bristol Hospital, Waterbury Hospital, Milford Hospital, New Milford Hospital, Windham Hospital in Willimantic, and the West Haven VA — have no stroke certification.

Even with more hospitals nationally certified, Connecticut is lagging in some areas of care, said Dr. Joseph Schindler, an associate professor neurology and neurosurgery, director of Acute Stroke and TeleStroke Services and director of the Vascular Neurology Fellowship Program at Yale New Haven.

“It’s left up to the hospitals to make investment in providing stroke care,” Schindler said. “Connecticut is a couple of states behind more progressive states like Rhode Island or Massachusetts when it comes to stroke care.”

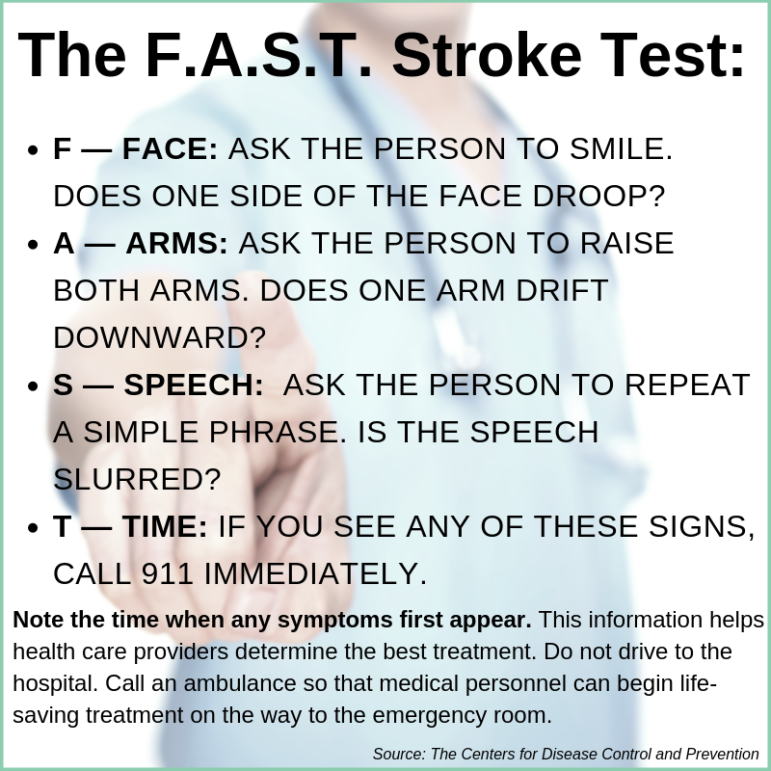

Connecticut’s EMS protocols, updated in 2017, delineate the steps emergency responders should take to transport a stroke patient to a hospital quickly. The steps include notifying a hospital immediately that a stroke patient is on the way and getting witness information on when symptoms started. But the protocols don’t specify where EMTs should transport a stroke patient.

Rhode Island, Virginia and Colorado are among a handful of states that require EMTs to transport a person suffering from a stroke to a hospital designated as a comprehensive stroke center. Massachusetts legislators are considering implementing similar protocols. Current Massachusetts law requires EMTs to take patients directly to a primary stroke center.

Nationally, about 140,000 people die of a stroke annually, and more than 795,000 people will have a stroke, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports.

In 2017, 1,403 people died in Connecticut from strokes, a death rate of 27.8 per 100,000 residents — the third lowest rate in the country, the CDC reports. Connecticut’s stroke death rate has remained below the national average of 37.3 per 100,000 people since 2015, the CDC said.

By comparison, states in the “stroke belt”— such as Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee — have a death rate 10% higher than the national average, according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Stroke Care

In addition to providing top-level stroke care, Yale and Hartford offer telestroke services to some hospitals, which provides quick access to neurological experts by video screen.

Lisa Backus Photo.

Dr. Richard Kamin, EMS director and associate professor at UConn Health.

Yale’s telestroke services are provided to nearly a dozen hospitals, including Sharon Hospital, St. Francis Hospital & Medical Center, Griffin Hospital, and Yale’s St. Raphael’s campus, Schindler said. Greenwich Hospital is expected to join the telestroke program with Yale in the coming months.

Hartford Hospital’s Telehealth Network includes Windham Hospital, Charlotte Hungerford Hospital, MidState Medical Center in Meriden and Backus Hospital in Norwich, all of which are under the umbrella of Hartford Healthcare.

The immediate video conferences allow physicians to receive expert consultations on the appropriate use of an intravenous drug to break up clots. The drug must be administered within 4½ hours of the onset of stroke symptoms. The video conferencing assists in patient evaluation to determine if a transfer to a higher level of stroke care facility is needed.

“An acute stroke-ready hospital is probably not going to have all the fancy tools, but they do have a team trained to immediately deal with stroke patients and get them where they need to go,” said Rommie Duckworth, an emergency responder in Ridgefield and the founder of the New England Center for Rescue and Emergency Medicine.

Stroke Policy Changes Under Review

Connecticut officials are continually reviewing stroke care through the state Stroke Advisory Committee, which is working with EMS officials to examine protocols for emergency responders.

One concept being discussed is whether it’s quicker and more effective to bring patients to the closest hospital, no matter what the certification level, to have the patient evaluated to see if they are a candidate for a thrombectomy, said Raffaella Coler, the director of the Office of Emergency Medical Services at the state Department of Public Health (DPH).

One concept being discussed is whether it’s quicker and more effective to bring patients to the closest hospital, no matter what the certification level, to have the patient evaluated to see if they are a candidate for a thrombectomy, said Raffaella Coler, the director of the Office of Emergency Medical Services at the state Department of Public Health (DPH).

“The need for interventional treatment (thrombectomy) is what would prompt transfer to a higher level of care,” Coler said. “This way the patient would get the treatment needed if appropriate in the shortest amount of time but still have the needed evaluation to see if they would benefit from transfer.”

About 80 percent of stroke victims have ischemic strokes, which are caused by blockages in the arteries leading to the brain, according to Dr. Richard Kamin, the EMS director and an associate professor at UConn Health, who is also an advisory committee member.

Another 10-15% have hemorrhagic strokes, which are caused by aneurisms or bleeding on the brain. Both types of strokes can cause death or severe disability if not treated quickly and properly. About 10% of ischemic stroke victims are appropriate for evaluation for a thrombectomy, with about 5% of those receiving the procedure, Kamin said.

Kamin said that bypassing a hospital that is close in order to transport a patient directly to a comprehensive stroke center could also have negative impact. “There is a sacrifice you make when you go past one hospital to another,” he said. “We know that if you have certain types of injuries you are taken to trauma center. Patients who are taken there have a better survival rate with less complications. It’s also true with certain types of heart attacks. We’re in the process of trying to figure that out for stroke.”

Officials have been working since 2014 to make legislators aware that the state needs updated stroke policies after funding for a DPH state stroke care hospital designation program ran out.

In a medical crisis where “time is brain,” every minute counts, which is why the state needed a system of care after the state’s designation program expired, said Dawn Beland, a registered nurse and coordinator of Hartford Hospital’s stroke center, who sits on the advisory committee.

“It helps us make sure that we are being the most efficient in passing that patient from EMS to the emergency department to the next level of care,” Beland said.

As part of the advisory committee’s continued work, every hospital in the state is now being assessed for its stroke care capabilities, Kamin and Coler said. Hospitals that don’t have the capability for stroke treatment should be transparent about what they can and can’t do, Kamin said.

“I think we owe the people of Connecticut, regardless of where they live, an understanding of what’s available to them in their local community,” Kamin said.

At the same time, the committee is trying to determine how to make sure everyone in the state has access to timely and effective stroke care, Kamin said.

“We have gaps,” Kamin said. “Those gaps are being looked at and hopefully we’re coming up with ways to address them.”