Cancers linked to the human papillomavirus (HPV) rose dramatically in a 15-year period, even as the rates of young people being vaccinated climbed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported.

The 43,371 new cases of HPV-associated cancers reported nationwide in 2015 marked a 44 percent jump from the 30,115 cases reported in 1999, according to a CDC analysis.

HPV vaccination rates have improved over the years, but not fast enough to stem the rise in cancers, the CDC said.

Oropharyngeal (throat) cancer was the most common HPV-associated cancer in 2015; accounting for 15,479 cases among males and 3,438 among females, the CDC data show.

iStock Photo.

In Connecticut, 58.4 percent of girls age 13 to 17 and 37.8 percent of boys received three doses of HPV vaccine.

HPV infects about 14 million people each year and between 1999 and 2015 rates of oropharyngeal (throat) and vulvar cancer increased, vaginal and cervical cancer rates declined, and penile cancer rates were stable, according to the CDC.

“The [overall rise] seems to be mostly driven by oropharyngeal cancers,” said Dr. Sangini Sheth, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at Yale School of Medicine.

“Vaccination is key to preventing those cancers,” said Sheth, who also is an associate medical director and director of colposcopy and cervical dysplasia at Yale New Haven Hospital’s Women’s Center.

“Oropharyngeal cancer is most common in men, and HPV vaccination rates, while they are rising in the U.S. and Connecticut, became routine for boys later [than girls]. And the rate of vaccinations among boys has definitely lagged that of girls. Hopefully, we will see vaccinating our boys have an impact on oropharyngeal cancer, but that’s going to take time.”

The push to vaccinate adolescents against HPV is a relatively recent development. The vaccination was included in the routine immunization program for females in 2006 and for males in 2011, according to CDC.

At one time, the HPV-vaccine was viewed largely to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, and some parents “resented” it and thought it was unnecessary for their children, according to Dr. Richard Brauer, section head of otolaryngology at Greenwich Hospital.

Now it’s marketed as a cancer vaccine and parents have become more receptive, said Brauer, who also has a private practice, Associates of Otolaryngology, in Greenwich.

In 2017, 65.5 percent of adolescents aged 13 to 17 nationwide had at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, up 5.1 percentage points from 2016, according to CDC data released in August.

In Connecticut, 75.4 percent of girls aged 13 to 17 had one dose of the vaccine, 67.1 percent had two doses and 58.4 percent received three doses. Among males, 67.3 percent received one dose, 58.8 percent got two and 37.8 percent got three, the 2017 data show.

But even amid overall gains, hurdles remain: gender disparity persists, and many teens received the first vaccine dose but failed to get necessary subsequent doses.

Children who are 11 or 12 years old should get two shots of HPV vaccine six to 12 months apart, according to the CDC. Adolescents who get their shots less than five months apart need a third dose of the vaccine, as do all children older than 14. Three doses also are recommended for people ages nine to 26 who have certain immunocompromised conditions.

Children who are 11 or 12 years old should get two shots of HPV vaccine six to 12 months apart, according to the CDC. Adolescents who get their shots less than five months apart need a third dose of the vaccine, as do all children older than 14. Three doses also are recommended for people ages nine to 26 who have certain immunocompromised conditions.

“It falls on the parent” whether children get vaccinated, said Dr. Bradford Whitcomb, chief of gynecologic oncology at UConn Health. “People associate HPV with female stuff. It needs to be pushed that we’re not just preventing female cancers.”

While it’s encouraging that vaccination rates are climbing, “we just may not see the benefit of that for years to come,” Whitcomb said. “It’s going to take a longer time, especially with the development of cancer, to see the effect. After the HPV infection, it can take years for a cancer to develop.”

Many people exposed to HPV will never get cancer, doctors say.

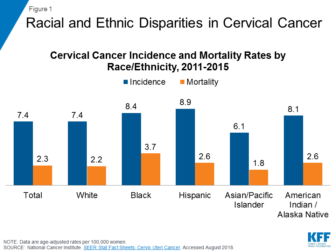

The most common HPV-associated cancer among women is cervical cancer. Data show rates of that cancer are falling, but there are racial disparities.

Between 2011 and 2015, Hispanic women had the highest incidence rates of cervical cancer at 8.9 percent, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation. That compares with 8.4 percent among black women, 7.4 percent among white women and 6.1 percent among Asian and Pacific Islander women.

Cervical cancer mortality rates also showed racial disparities during that time. Black women had the highest mortality rate at 3.7 percent, compared with 2.6 percent among Hispanics, 2.2 percent among whites and 1.8 percent among Asians and Pacific Islanders, data show.

It is crucial for doctors to talk to young patients and their parents about the HPV vaccine, even if it spurs conversations parents may feel awkward having, Sheth said.

“Clinicians need to feel comfortable normalizing the HPV vaccine and really present the HPV vaccine as a cancer prevention tool,” she said.