Iasiah Brown, 25, of New Haven, said he does not see a need for a primary care doctor for himself and his daughter, opting to visit clinics in the area instead of waiting up to two weeks for an appointment at a doctor’s office.

Brown is among the 83 people who said they didn’t have a primary care doctor in response to a health-care usage survey by the Conn. Health I-Team and Southern Connecticut State University. The team surveyed 500 people and interviewed dozens statewide between January and March.

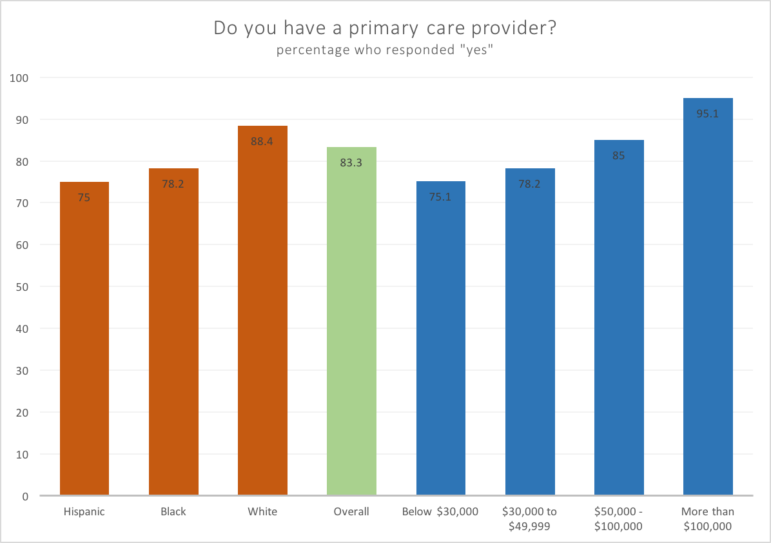

About 83 percent of respondents said they had a primary care doctor, but the rate was lower for African American (78 percent) and Hispanic respondents (75 percent). Meanwhile, white respondents were more likely than the average—at 88 percent—to have a primary care doctor. These numbers have decreased since 2015, when C-HIT conducted a similar survey. In 2015, 93 percent of whites, 84 percent of African Americans, and 86 percent of Hispanics had a primary care doctor.

What residents had to say about their health care, hosted by SCSU student Michael Riccio.

The survey results highlight health care disparities between wealthier residents and those in lower income brackets, and between white respondents and minorities—findings that mirror those of the 2015 study.

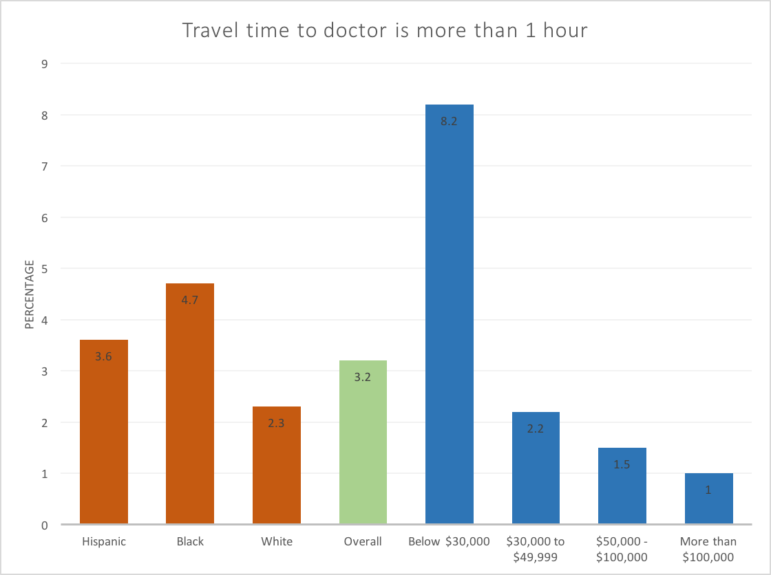

In general, white residents and those making more than $50,000 a year were more likely to have health insurance and use it. Those over 50 years old in both groups were more likely to have undergone a colonoscopy. The wealthier respondents more often lived close to their primary care doctor.

But in some cases, those making below $50,000, and people of color, were more likely to have had some preventive care screenings, such as chest X-rays for smokers, screenings for depression, and interventions from doctors regarding their weight.

About 110 people said even though they had insurance, there were barriers preventing them from accessing health care. Of those, 54 cited co-pays, 39 said time or travel expenses, and 17 said there was a language barrier to accessing health care.

For Natasha Gerasimopoulos, 36, of Milford, the problem is finding a doctor covered by insurance. Gerasimopoulos, who is insured through Husky Health along with her son, doesn’t have co-pays for her office visits, but she said it’s hard to find specialists who take Husky.

“The doctors’ offices will say ‘Oh, we don’t take that insurance,’ or ‘We stopped taking it a long time ago’,” Gerasimopoulos said. Or, she said, if she can find a doctor who takes her insurance, the office is far from her home.

Most people, at 92.6 percent, reported having health insurance for 2018. But Hispanics and blacks were less likely to have health insurance, at 80.2 percent and 89.2 percent, than whites, at 97.7 percent.

More people reported being uninsured than in the 2015 survey, when 3.6 percent said they had no medical insurance. Connecticut’s uninsured rate for 2016, the most recent numbers available from the National Center for Health Statistics, was 5.8 percent.

Recent changes to the Affordable Care Act, first enacted in 2010, have negatively impacted health care access, according to Pat Baker, president of the Connecticut Health Foundation.

An example, she said, is a change in the number of state residents who qualify for Medicaid.

An example, she said, is a change in the number of state residents who qualify for Medicaid.

“Originally Medicaid in Connecticut covered individuals up to 185 percent of poverty,” Baker said. “What we saw happening since 2015 is that has been reduced to 155 percent of poverty, with the rationale that all those [excluded], about 18,000 people, could go get coverage through the exchange, Access Health CT.”

Instead, Baker said, only 20 percent of those dropped by Medicaid were able to purchase insurance through the exchange. The Connecticut Health Foundation and Access Health CT believe cost was a major factor, as survey respondent Beverly Malerba of Ansonia said. “I can’t afford it, really,” she said. “I wish [health care] was universal, like they have in Canada.”

“What remains consistent is the disparate rate between the connection to care between the majority population and people of color, particularly African Americans,” Baker said.

Of those with insurance surveyed by C-HIT:

• 57 percent said they receive insurance through an employer plan;

• 17 percent of respondents are insured through Medicaid;

• 12 percent through Medicare;

• about 8 percent purchased insurance through the Access Health CT exchange;

• 3 percent said they had private insurance, but didn’t indicate how they received it; and

• 1 percent are insured through both Medicaid and Medicare;

One of the barriers to care is travel time to a doctor, especially for those earning less than $30,000 annually.

Half of the respondents made more than $50,000 a year, and 56 percent were women. The respondents skewed younger, with 65 percent responding they were in their 40s or younger, and 29 percent in their 20s. About 53 percent of respondents were white, 20.7 percent were African American and 19.5 percent were Hispanic.

Women’s preventive care results were mixed. Overall, 87.7 percent of women over 40 had received a recommended mammogram in the last year, and 77.4 percent of women over 20 had received a recommended Pap test.

Women making more than $50,000 were more likely to have received Pap tests. But the results for women over 40 who had received mammograms in the last year were split on income levels. Those making $100,000 or more were most likely to have had a mammogram in the last two years (93 percent), but those making less than $30,000 were close behind (89 percent).

Black women were the most likely to have received a mammogram (93 percent) and Pap tests (91 percent). White respondents stated they had received recommended mammograms at 89 percent, and Pap tests at 76 percent. For Hispanic women, the results were 75 percent and 71 percent, respectively.

In dozens of interviews, Connecticut residents spoke of the challenges with their health care.

Like Steven S. Siebold, 44, of Trumbull, who said he pays a high premium for his healthcare—about $1,400 a month.

“It’s terribly expensive for what I get,” Siebold said.

Maria Zhumi, of New Haven, said while she has health care through the exchange, she hasn’t been able to get her 9-year-old daughter on the plan because she doesn’t have a Social Security number. Zhumi said she has been paying for her daughter’s health care out of pocket.

Confusion over her citizenship status is preventing Mayelin Jimenez of New Haven from obtaining health care, she said. When she lived in New York, she paid for private insurance, she said, but canceled that policy when she moved to New Haven in November. When she tried to obtain HUSKY insurance, she was told she had to have been living in the U.S. for five years to meet Connecticut’s eligibility requirements. Jimenez said she must wait until July before she qualifies for HUSKY benefits.

“What if I have an accident?” she asked. “I have no insurance.”

Laurinda Bernardo, 65, of New Britain, said rising deductibles have caused stress for her family. Her 2-year-old granddaughter has mitochondria depletion syndrome and requires constant care. Bernardo’s daughter had good insurance, but it still came with a $5,000 deductible. The next year, the deductible increased to $6,000.

“So that year she ended up paying $16,000 just to have the bills paid,” Bernardo said. “Who has that kind of money just sitting around?”

Barbara Collado, a mother of three from New Haven, has had HUSKY A insurance for around 10 years, ever since she moved to Connecticut from Puerto Rico.

In an interview conducted in both Spanish and English, Collado said her HUSKY coverage helped as she and her children have undergone evaluations for health issues. Collado said HUSKY paid for everything. The experience, she said, changed how she viewed her health, and she began seeking health care regularly at her primary clinic, the Cornell Scott-Hill Health Center.

Collado said, however, that it takes her two buses to get to the Hill Center. When the bus is late, she’s late for her appointments. But it’s worth it to Collado.

“I have a good relationship with them,” she said.

Kaitlyn Regan is a senior at Southern Connecticut State University.

This project was reported by the students in the Multimedia Journalism course at Southern Connecticut State University, taught by Assistant Professor Jodie Mozdzer Gil. The students are: Ryan Conchado, Kevin Crompton, Jailene Cuevas, Melanie Espinal, Jonathan Gonzalez, Ethan Goodrich, Andrew Hans, Megan Hill, Quinn O’Neill, August Pelliccio, Michael Riccio, Alyssa Rice and Regan.

Lisa Massicotte, Jeniece Roman and Matt Wynn, C-HIT data specialist, contributed reporting.

Vern Williams Photo.

Southern Connecticut State University students who worked on this project, under the supervision of Assistant Professor Jodie M. Gil