Three years ago, Meredith Phillips’ mother, Georgia Svolos, fell and broke her kneecap, setting off a downward spiral that landed her in nursing homes on and off for a year. In one facility, she fell and broke her knee again, necessitating more surgery. All of the facilities were noisy and chaotic, and one smelled of feces.

So, when Phillips learned recently about moves by the Trump administration to ease regulations and fines on nursing homes, she was alarmed. “I’m horrified and frightened,” says Phillips, who lives in Westbrook. Her mother, now 78 years old, is living independently again—but her future is uncertain.

“These vulnerable people are at the mercy of the nursing homes,” Phillips says. “The homes need strong oversight. They don’t have enough, and this is going to make it even worse.”

After Donald Trump was elected president, the American Health Care Association, representing the nursing home industry, sent letters to him and Thomas Price, who was then his Health & Human Services secretary, calling for modifications of Obama-era regulations. Since then, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which oversees the nursing home industry, has published a series of new guidelines that address issues raised in the letters.

After Donald Trump was elected president, the American Health Care Association, representing the nursing home industry, sent letters to him and Thomas Price, who was then his Health & Human Services secretary, calling for modifications of Obama-era regulations. Since then, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which oversees the nursing home industry, has published a series of new guidelines that address issues raised in the letters.

Leaders in the Connecticut’s nursing home industry say the changes are justified and will improve outcomes for nursing home residents. “The previous rules were overreaching, burdensome and punitive. They diverted scarce nursing home staffing resources away from hands-on care,” says Matthew Barrett, CEO of the Connecticut Association of Health Care Facilities, which represents more than 150 of the 224 skilled nursing facilities in the state and is affiliated with the American Health Care Association.

Barrett describes the recent CMS revisions as “a modest response to issues raised but not addressed to the industry’s satisfaction in the 2016 rule revisions.” He hopes more changes will come.

Advocates for seniors and nursing home residents are skeptical of the Trump administration’s motivations. “CMS is dismantling the enforcement system and making it more difficult and less likely for any enforcement against facilities with serious deficiencies,” says Toby Edelman, a senior attorney at the Center for Medicare Advocacy. “They’re not seeing their responsibility as helping to assure the health and welfare of residents. They’re working to please their customers, the nursing homes.”

Meanwhile, Connecticut has its own nursing home laws and regulations, and assesses fines against facilities that violate them. Under legislation passed last year, the upper limit for fines for each violation quadrupled to $20,000.

“Fortunately, we do not rely solely on federal regulations for our oversight of nursing homes, and our state laws and regulations protecting nursing home residents remain in place and will continue to be enforced,” says Maura Downes, director of communications for the Connecticut Department of Public Health (DPH).

Connecticut issued 73 citations against nursing homes last year, down from 96 the previous year, according to the DPH. The fines typically ranged from a few hundred dollars to $3,000.

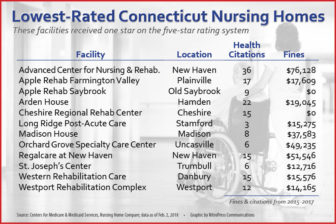

The federal government processed fines for 128 Connecticut nursing homes over the past three years, according to the CMS website. The remedies included more than $160,000 in fines to Apple Rehab Rocky Hill, more than $75,000 to Advanced Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation in New Haven, and nearly $50,000 for Orchard Grove Specialty Care Center in Uncasville.

A spokesman for Advanced Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation said the facility came under new ownership in 2016, and they are committed to improved performance by investing in facilities and staffing. The other nursing facilities did not respond to inquiries.

CMS’ revisions to nursing home regulations have trickled out over a number of months—barely attracting notice among the general public. They include:

• Ending an Obama-administration prohibition on pre-dispute agreements to binding arbitration. You can’t sue nursing homes if you sign the agreements.

• Advising monitors to consider the extent to which noncompliance is a one-time mistake or accident, rather than evidence of a systemic problem.

• Freezing changes in the ratings for facilities for one year while the five-star system is revised.

• Imposing an 18-month moratorium on certain violation remedies.

• Discouraging daily fines, which can quickly mount up.

Steve Hamm Photo.

Advanced Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation, New Haven, has paid over $75,000 in fines to CMS.

CMS insists that most of the changes are aimed at improving care and safety for residents, partly because they are expected to improve compliance with the law. The moratorium on certain remedies, for instance, is designed to enable facilities to train their staffs in the intricacies of the 2016 regulatory changes, according to an agency spokesman. He believes the changes won’t reduce fines when strict penalties are warranted. “CMS has not sent guidelines to states that discourage regulators from levying fines. In fact, our memo specifically calls for per-day civil money penalties when abuse is identified,” said the spokesman, who said his name could not be used.

The guidance concerning arbitration, which resulted from a court decision in the industry’s favor, requires nursing homes to make it clear to people they won’t be able to sue the facility if they sign the agreements, the spokesman said.

Lisa Freeman, head of the Connecticut Center for Patient Safety, says the rule changes make it even more important for the families of elderly people to do extensive research before they choose a nursing home. The federal government’s Nursing Home Compare website enables people to look up compliance records of every facility in the country that accepts Medicare or Medicaid payments. Even though the star ratings will be frozen, detailed reports of deficiencies found during inspections will still be available.

Freeman advises people to talk to family members of patients, and always tour the place before you commit. “If you see a lot of patients sitting in wheelchairs in the hallways, that’s a signal that there may be problems,” she says.

The $130 billion-a-year nursing home industry is under intense economic pressure these days. Many facilities have seen their patient populations decline as more people choose assisted living facilities or receive care in their homes, and hundreds of homes nationwide have closed their doors. Meanwhile, Medicaid funding, which pays the bills for about 70 percent of nursing home patients, hasn’t kept up with cost increases.

In spite of the decline in nursing home populations, the aging of the Baby Boomer generation means there will be rising demand for all sorts of elder care in the coming years.

Many people will seek care in nursing facilities eventually. And they won’t just be poor people. The average cost of a stay in an assisted living in Connecticut is $5,000 per month, according to The Elder American Care Research Organization. And most assisted living facilities don’t accept Medicaid. So many middle-class people quickly spend down their savings and, soon, they’re relying on nursing homes and Medicaid.

Pat Endel, who cares for her 96-year-old mother, Louise Endel, in their North Haven home, points out that her mother was a civic leader in the New Haven area for much of her life, and now has no financial resources. If Pat can no longer care for her, she will have to go into a nursing home and depend on federal assistance. That worries Pat Endel. If regulatory changes lower standards of care, “there will be no real safety net for people on Medicaid,” she says.