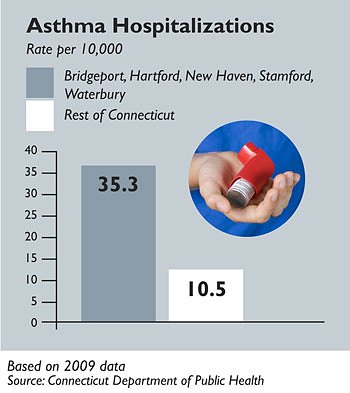

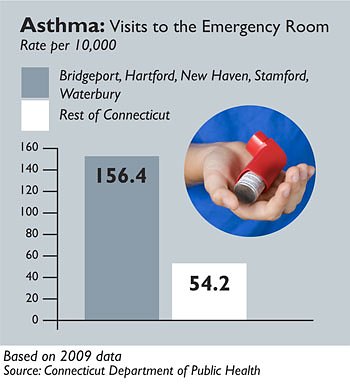

Residents in Connecticut’s five largest cities are nearly three times more likely to be hospitalized for asthma – and twice as likely to die from it—as residents in the rest of the state, according to new data from the state Department of Public Health.

The prevalence of state adults reporting asthma has increased from 7.8 percent in 2000 to 9.4 percent in 2009, the most-recent data shows, but it is residents in the five cities—Bridgeport, Hartford, New Haven, Stamford and Waterbury – who bear the brunt of it.

The five largest cities had asthma hospitalization and emergency department rates that were about three times higher than the rest of the state.

This costs more than $17 million in hospitalization charges and $6 million in emergency department visits a year, most of which, according to the state health department, is paid for with public funds, Medicare and Medicaid.

The disparities persist despite an effort launched by the state in 2000 to level and reduce the disease burden. The State Asthma Program works with local health departments to help people with asthma manage their disease, mainly by sending asthma specialists into homes to do environmental assessments and identify asthma triggers.

State public health experts say disparities in asthma are hard to combat because they stem from socioeconomic differences, including access to medical care, health insurance and the condition of housing.

People with low incomes often live in substandard housing in neighborhoods where the air quality is poor. Typically, they don’t have health insurance, which leaves them with limited access to medical care and the professional information they need to manage their asthma.

What frustrates caregivers the most, according to Michael Corjulo, a pediatric nurse practitioner at the Children’s Medical Group, in Hamden, and a certified asthma educator, is that asthma is the single most avoidable cause of hospitalization in Connecticut and other parts of the country, yet it’s the second most common reason for admission.

“That’s it right there. That sums up the entire disparity,” he said. “There’s no excuse for asthma to go uncontrolled. We have the knowledge and skills to avoid those hospitalizations.”

So what’s the big obstacle? Corjulo said that’s easy. The health care system is not structured to support chronic disease management. He said chronic disease management requires two basic components: patient education and care coordination, neither of which is reimbursed by Medicaid or many private carriers. “That, in a nutshell,” he said, “is the missing link toward sustainable progress.”

He added that while lip service is paid to the importance of preventive medicine, “nobody wants to pay for it.” In the case of asthma, that means that most insurance companies and Medicaid don’t cover patient education for the purpose of disease management. This is a shortsighted answer to budgetary constraints, Corjulo said, because those savings are more than offset by the cost of the acute care that inevitably results when patients don’t know how to manage their illness. “There’s a lot of research clearly showing that we can decrease hospitalizations and emergency room usage through education,” he said. “Those things make a big difference when you look at asthma outcomes.”

Corjulo acknowledged that some patient education happens in the context of an asthma-related medical appointment, but when patients are in an acute state, they aren’t in the best condition to absorb a lesson on long-term disease management. “In an ideal system, which we know works, you do a follow-up visit with the patient when he or she is calmer and feeling better,” Corjulo said. “That way you can spend a bit of time, sort it out and figure out what the patient needs to understand to manage their illness.”

The other problem, according to Corjulo, is that people on the health care team who provide educational services aren’t typically reimbursed for that work. As it now stands, he said, only providers with prescriptive authority (physicians) may be reimbursed directly for those services. “Part of the solution is for nurses, asthma educators, community health workers and other trained professionals to be reimbursed for their work,” he said. “But there’s no recognition of that type of care in any payer source for health care in Connecticut.”

WebKazoo Graphic

Shift To Chronic Care Management

Mark Schaefer, the state Department of Social Services’ director of medical care administration, pointed out that one reason the state’s asthma prevalence numbers aren’t improving is because asthma is a chronic condition. One doesn’t get “cured” of asthma; one’s asthma is either managed or it’s not, he said.

That said, he agrees with Corjulo that the state has to change its reimbursement structure to support chronic care management. But he said that’s exactly what’s happening. “We’re focused on a fairly sweeping transformation of the way we administer health care services with one of the main points being to focus on certain significant chronic conditions, such as asthma.”

The term they use for this new health care model is “patient-centered medical home,” and Schaefer said the transition in Connecticut is set to be up and running by January of 2012. “The provider will be compensated for meeting a more advanced standard of primary care, emphasizing things like educating patients in the management of chronic illnesses.”

Schaefer said he’s “quite enthusiastic” about the medical home model. “It’s a major break in how we’ve administered Medicaid benefits. It has enormous potential.” He added that private insurers set their own reimbursement policies, but he’s optimistic they’ll fall in line with the state’s new system for reimbursing practices that provide chronic care management.

A key element of the new plan will be having an asthma educator on the primary care team, and that person should be reimbursed at a reasonable level. He said DSS is exploring ways to compensate those providers appropriately.

While asthma experts welcome these changes as a move in the right direction, they know it will take time before it is fully operational. In the meantime state and local health officials are partnering on several fronts to combat the prevalence of asthma.

•The Statewide Asthma Program, unveiled in 2004 and revised in 2009, is a comprehensive plan for combating asthma in Connecticut, including implementation of interventions and initiatives that address clinical management, professional education, parent education, the environment, surveillance, and public awareness.

•Putting on Airs (AIRS) sends trained specialists into homes to make environmental assessments and look for asthma triggers. Follow-up visits are made after two weeks and again after three months. Referrals come from family, emergency department physicians, local health departments and school nurses.

•Easy Breathing is a clinically proven national program developed by Dr. Michelle Cloutier of the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center. It provides primary care physicians with a system to quickly and easily assess, treat and re-evaluate children’s asthma. One study found a 91 percent decrease in emergency room visits among Connecticut children who were treated using the Easy Breathing program.

•Healthy Homes is a national program that addresses the housing conditions, such as dust mites, cockroaches, pets and rodents, molds, tobacco and other indoor air pollutants, that are asthma triggers.

New Training

Eradicating the disparity in the prevalence of asthma is also a priority for state health care providers. “They’ve built asthma disparities into the State Asthma Plan,” said Dr. Stephen Updegrove, a medical advisor for the New Haven public schools. They’re also arming school nurses with better training and supplies to respond to students who have attacks and a best practices educational effort for families.

According to the state’s 2010 school-based asthma surveillance report, asthma prevalence among public school students remained virtually unchanged – at about 13 percent – from the fall 2006 to the spring 2009. Students in New Haven, Hartford, Waterbury and Bridgeport (municipalities with the lowest socioeconomic classification) had the highest asthma rate, at 19.2 percent, while students from communities such as Darien, Madison and Greenwich, with the highest socioeconomic classification had the lowest, at 7.4 percent.

Katie Ruane, a nurse and certified asthma educator at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, knows firsthand how, when armed with the right information, patients can manage their asthma. While helping her son learn to live with the illness, Ruane developed a passion for educating others about asthma management. “So many people just don’t understand how to treat it; they think it’s something you just have to live with,” she said.

“But I know it doesn’t have to control your life. It should be the other way around; you can control your asthma.”

Just as no single factor causes asthma, the war against asthma can’t be fought by health care providers alone. Jennifer Kertanis, executive director of the Ledge Light Health District, in southeastern Connecticut, said they are now partnering with experts from housing, environment, education the transportation sectors to combat the issue in a more multi-factorial way.

Corjulo said he takes it personally if a patient is hospitalized with asthma. “I feel like we failed.” It is the rare child who has asthma that is so persistent it can’t be managed, he said. “In the vast majority of situations, there is simply no excuse for it not to be controlled.”

Excellent article Jennifer. Thanks for doing such in-depth investigation. Also some great comments from the readers. Although I am quite concerned about indoor air quality, especially in public housing (I have seen mushrooms growing from bathroom walls) I believe that outdoor air is critical. Although indoor air is often more contaminated than outdoor air, it is difficult to get indoor air cleaner than outdoor air. I tested the air for particulates in my office and they were directly proportionate to the particulates in the outside air. People who have the wherewithal to hire private consultants for air quality should feel privileged. People shouldn’t have to buy personal clean air. Clean air is a human right. I believe that the increasing rates of asthma are due in large part to exposure to some of the 70,000 or so chemicals that are untested for health effects before being released into the environment or used in consumer products. We have the ability to regulate the chemicals in the air that probably contribute to asthma. We should do so.