Betty Williams says giving up crack cocaine was easier than her ongoing struggle to quit cigarettes.

“A cigarette is a friend,” said Williams, who lives with schizophrenia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

People with mental illness account for 44% of the cigarette purchases in the United States, and they are less likely to quit than other smokers. High smoking rates among people with mental illness contribute to poorer physical health and shorter lifespans, generally 13 to 30 years shorter than the population as a whole.

About 37% of men and 30% of women with mental illness smoke. The rate of smoking among whites with mental illness is 35%; blacks, 33.6%; and Hispanics, 27.2%, according to Mental Health America. While smoking rates are dropping in the U.S., a decade-long study that began in 2000 showed no consistent decrease for people with mental illness.

Help to quit smoking can be hard to find.

In this podcast, C-HIT’s Colleen Shaddox explores the difficulties people with mental illness face in finding programs to help them quit smoking.

“The quit rates are so low that physicians are kind of weary about getting in there and fighting the fight,” said Dr. Paul Sachs, director of Stamford Health’s Division of Pulmonary Medicine. Quit rates are low for all smokers, he added, but even lower for people with mental illness. Among the general population, less than 10% of smokers will succeed in quitting for six months in any given attempt.

“We need physicians to make it a priority,” Sachs said. He noted that office visits in a typical practice may be too short to have a meaningful discussion about tobacco. He suggests that doctors either designate a nurse practitioner or physician assistant as the smoking cessation specialist in the practice or refer patients out to someone who can support them in quitting.

Sachs heads the health system’s smoking cessation program. The program is accessible in the psychiatric ward but he found few takers. “If you talk to 20 people about it and one of them stops, it’s still worth it,” Sachs said.

Jean-Marie Monroe-Lynch developed a smoking cessation program for people in Wheeler Clinic’s Adult Services Department, which serves the most seriously ill among the agency’s clients. Lynch, who directs the department, said 70% of the clients in it smoke. With support, including group counseling, nicotine gum and referrals for sessions of acupuncture and exercise, 15% of those who signed up managed to quit for a week—a high enough success rate that Lynch wants to expand it. Even for those who did not remain smoke-free, there was a benefit, as smokers typically go through multiple attempts before finally quitting. “Some people didn’t successfully quit, but it gave them that thought process,” she said.

Lynch sees potential for cessation programs embedded in mental health organizations, where people can manage the depression and anxiety that led them to smoke in the first place. “The reason that most people start smoking with mental illness is that it masks their symptoms,” she said.

Colleen Shaddox Photo.

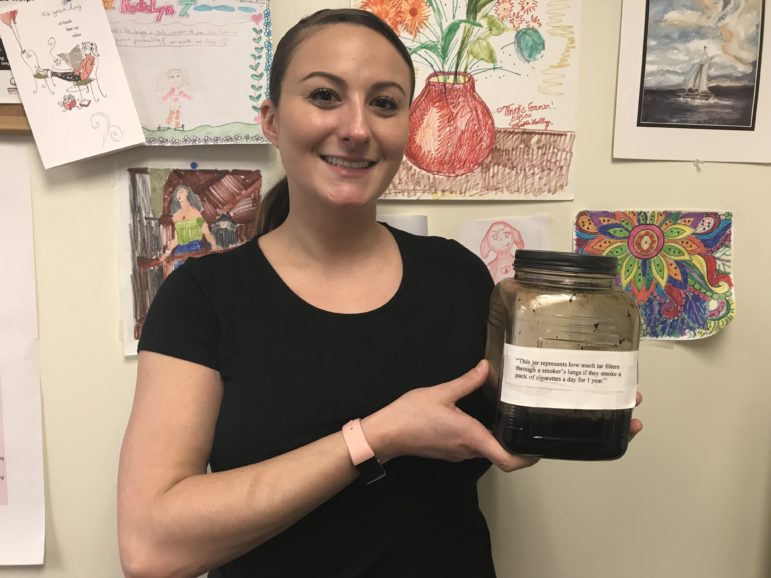

Katelyn Trauger, a social worker at Fellowship Place, holds a jar that she says represents the amount of tar a smoker’s lungs accumulate in a year.

Connecticut used to fund smoking cessation programs specifically for people with mental illness, using money from a multi-state lawsuit against cigarette companies. Now that money goes directly into the General Fund. “There has been no new funding for tobacco control outside of Medicaid since 2015,” said Bryte Johnson, government relations director in Connecticut for the American Cancer Society. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that the state spend $32 million annually on tobacco control, but Connecticut has only spent a total of $29 million cumulatively since 2003, he said.

“It’s really unfortunate,” said John O’Rourke, director of CommuniCare, a mental health service program that serves greater New Haven. O’Rourke ran smoking cessation programs for people with mental illness, until the state funding ceased. Having programs that can address the interplay of mental illness and smoking is helpful, he said. “Quitting actually benefits their recovery,” he said. Abstaining from cigarettes can boost mood and give people a sense of accomplishment, according to O’Rourke.

Katelyn Trauger, a social worker at Fellowship Place, has charts to show clients, most of whom are low-income people with mental illness, how much money they will save from quitting. She also keeps a jar of brown goop in her office that represents the amount of tar a smoker’s lungs accumulate in a year of smoking a pack a day.

“It’s really, really, really difficult. A lot of people will use smoking as their last vice,” she said. Fellowship Place used to have a formal smoking cessation group, but Trauger ended that in favor of drop-in counseling, recognizing that keeping appointments can be difficult for the people she serves.

Cessation services for people with mental illness are rare enough in Connecticut that Trauger, who works in New Haven, gets calls from places like Wethersfield and Portland.

Williams is down to two cigarettes a day. “I can breathe now without wheezing,” she said. But she quickly added, “I have to stop.” With street drugs behind her, Williams is active in her church and community. She has a job. She has finally met her grandchildren. “That was miraculous!” she said. Williams wants to stick around for more experiences like that.

“I don’t want to die. I put the crack away,” she said. “I want to put the cigarettes away. I got to get right with myself. I don’t want to die just for a cigarette.”