As scientists measure the prevalence of COVID-19 in the sludge flowing from New Haven sewage treatment plants, they’re also finding that our biological waste can tell them much more about our collective pathologies.

Between March 19 and June 30, a group of scientists tested waste that had previously been used to detect COVID-19, looking for drugs and chemicals. The researchers found significant increases in three opioids, four antidepressants, and other chemicals in sludge from New Haven.

The analysis, by scientists from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES) and Yale University, offered the first glimpses of how the pandemic’s stay-at-home orders affected people’s behavior. It also underscored how important human waste can be as a resource for understanding public health and society’s habits. Diseases, drugs and chemicals all show up in feces, providing a major tool for public health studies.

Sara L. Nason, a CAES scientist, is leading the waste analysis, which found increases in fentanyl, hydromorphone and methadone in sludge taken from primary settling tanks in New Haven.

Nason said the goal is to understand how the pandemic changed people’s habits and health.

“We hypothesize that the changes in chemical concentrations will reveal interesting trends that correlate with public health outcomes.”

— Sara L. Nason

Fentanyl’s increase in the New Haven population reflected “both increased use in hospitals for patients on ventilators, and the nationwide trend of increases in accidental overdose deaths from illegal use,” Nason said.

Five years ago, the testing of human feces for substances “was something that I would talk to other people about, funding agencies, and they would kind of roll their eyes and say, ‘Yeah…’ It was not too much on the radar back then,” said Jordan Peccia, a professor of chemical and environmental engineering at Yale University. Peccia is working with Nason on the analysis using frozen samples from another project on which Peccia is working, a COVID-19 testing effort that analyzes sludge from six Connecticut treatment plants. Peccia’s Yale laboratory collects data and publishes the information on a public website. The lab tests the concentrated substance found at the bottom of the tanks where waste entering sewage plants in New Haven, Bridgeport, Hartford, New London, Norwich and Stamford goes to settle.

Peccia and at least eight other scientists hope to expand the sludge testing “to other diseases, to other viruses, to other locations around the world where they don’t have testing,” he said. They have applied for National Institutes of Health funding.

Rising Drug Levels

Besides the opioids, the scientists found six antidepressants in the sludge, and six disinfectants. Sertraline (Zoloft) increased in March, before there were reported shortages of that drug. Three other drugs showed a clear rising trend over the spring: doxepin (Silenor), citalopram (Celeva), and amitriptyline (Elavil). Tracking these drugs during the pandemic was important, Nason said, because studies have linked psychiatric illnesses and COVID-19.

Nason explained it this way: studies have shown “people with psychiatric illnesses are at risk for being diagnosed with COVID-19, and that COVID-19 infection is associated with new diagnoses of psychiatric illnesses.”

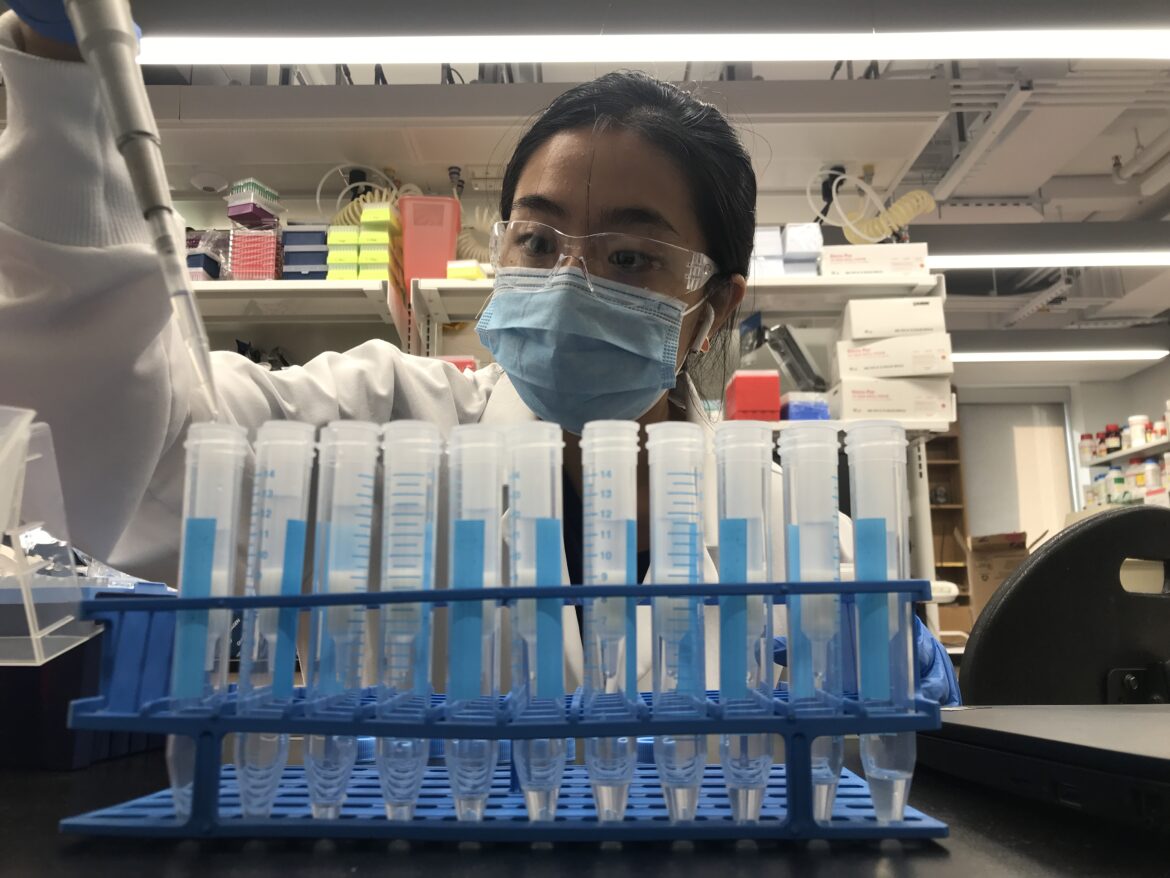

Steven Geringer/Yale University Photo

Sludge samples are placed into test tubes at Yale University.

Three of the six cleaners they found in the sludge are common wipes and sprays with quaternary ammonium disinfectants, known as quats, which scientists in the last decade have linked to reproductive and developmental problems in animals.

Nason said the CAES/Yale team’s research focused on “substances whose use we expect to be affected by the pandemic, such as antidepressants, opioids, and antiviral drugs.” They compiled their key findings in a poster presented last fall to the Society for Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. They plan to submit research papers for publication this winter.

The findings were mostly detected using a technique called suspect screening, in which a mass spectrometer collects molecular information and matches it through large databases. “Suspect screening is a very powerful technique because you don’t necessarily need to know what chemicals you are looking for ahead of time,” Nason said. “You find whatever signals in your data match the database entries. For example, we did not initially decide to look at disinfectants in the sludge, but we found several of them through our suspect screening analysis.” She added that they used other analytical standards to confirm their key findings, “so we are quite confident in our results.”

Peccia said the expansion of sludge testing could be used to study infectious diseases like norovirus; adenoviruses, which cause fevers, diarrhea, and more; all of the coronaviruses that cause colds; and bacterial diseases like tuberculosis and legionella, which causes legionnaire’s disease.

Sewage As A Resource

The long but spotty history of testing sewage for disease dates to the 1960s and a Yale study of the polio vaccine in Middletown. For at least 20 years scientists have been studying sewage, but much of their work focused on environmental issues. Human waste can reveal whether industry is following environmental regulations, and scientists can test for banned chemicals, such as fire retardants, linked to cancer.

These studies analyze the sludge left in the bottom of primary tanks after the water has settled. Scientists can also collect human waste by sampling the diluted soup of water and solid waste that flows under the streets.

Yale University Photo

Jordan Peccia

Peccia maintains that sampling the concentrated sludge is the most efficient method. Sewage treatment “takes in wastewater and it separates the bad stuff from the water. It puts out clean water, and then you have tons and tons and tons of material that was separated from that wastewater. Most of the bad stuff in the wastewater treatment plant gets left behind in the sludge,” he said.

However they are found — whether in the water known as “influent” or the settled sludge — Peccia said he estimates that more than half of infectious diseases show up in waste.

He said testing sewage could transform how doctors recognize and treat diseases where diagnosis is difficult and not always accurate, such as Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses, and Eastern equine encephalitis and other mosquito-carried diseases.

Tracking substances like nicotine, alcohol, heroin and opioids in sewage sludge shows how drug uses changes on weekends. “Those pieces of information are hard to come by otherwise,” Peccia said.

These studies will provide information that will correlate with other studies of human illness and behavior. “If hospital prescriptions and disposals of fentanyl increase over the same period of time as fentanyl concentrations in sludge increase, we can start to put together a story,” Nason said.

“But if that is not the case, the sludge data could be a sign for public health officials that illegal use needs to be further investigated,” Nason continued. “Overall, the sludge findings are most valuable when they can be supported with data from other sources that relate them to public health.”