Joseph Deane had been drug free for months before he overdosed in the bathroom of a restaurant in New Haven last December. He couldn’t resist when his dealer offered drugs. Unfortunately, the dope turned out to be fentanyl.

Deane, just 23 years old, had been fighting addiction for years, but fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, took his life because it’s 50 to 100 times more powerful than heroin. After months without drugs, his body couldn’t handle it.

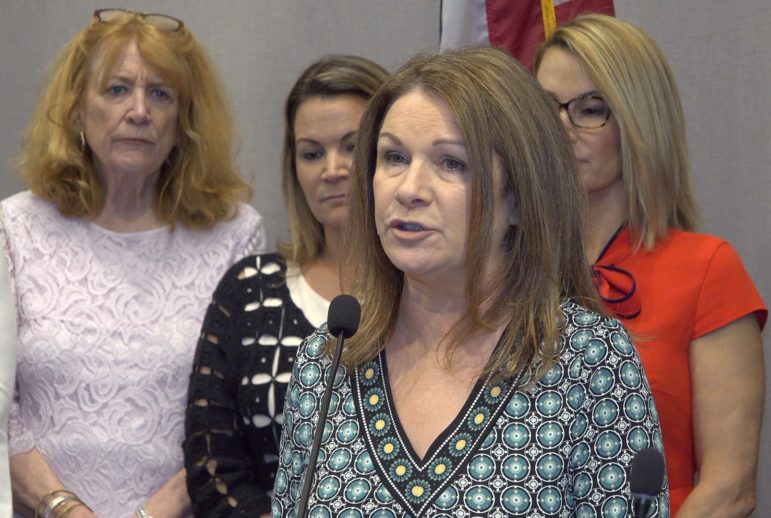

“Fentanyl is pure evil. We have to stop this,” says his mother, Lisa Deane. This spring she helped drive the passage of a new state law stiffening the penalties for selling illicit fentanyl. The measure was signed into law by Gov. Ned Lamont last Friday.

The Deanes are a white upper-class family in Madison, but fentanyl is an equal opportunity killer, affecting people of all types in cities, suburbs and rural areas. Five black men died from a mixture of cocaine and fentanyl in a 15-hour period in Hartford on June 3 and 4.

Those deaths came on top of a rapid increase in fentanyl-related deaths statewide over the past half-decade. Of 1,017 opioid deaths last year, 75% involved fentanyl. In 2012, it was just 4%. This year could be worse. As of June 10, Hartford had already recorded 45 opioid overdose deaths, compared to 24 at this time last year, according to police.

Political and health care leaders call this a full-blown health crisis. They say the rise of illegal fentanyl forces everybody to rethink their strategies.

Over the past few years, Connecticut has launched a slew of programs aimed at improving prevention and treatment for opioid use disorder. But now health care leaders say they need to expand programs more quickly, develop new ones and break down the barriers to treatment. That includes eliminating the stigma of drug dependency, which is the main reason people don’t seek care.

Among their priorities are educating people about the dangers of fentanyl; accelerating the distribution of the opioid antidote naloxone; and guiding people toward medications for opioid use disorder.

Methadone and buprenorphine satisfy cravings for opioids without making people high. They have been proven to keep individuals in treatment and reduce illicit drug use. “People can have all different kinds of ideas, but the science says this is the treatment that works,” says Dr. Gail D’Onofrio, physician-in-chief of emergency services at Yale New Haven Hospital.

A just-published study commissioned by the National Academies of Sciences, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives, concludes that people with opioid use disorder are up to 50% less likely to die when they are being treated long term with methadone or buprenorphine.

One of the challenges of fentanyl is that dealers mix it with heroin, cocaine and other drugs, and criminal suppliers manufacture counterfeit pain pills that contain fentanyl. In Connecticut’s wealthier communities, young people mix a variety of pills in bowls at parties and sample them without knowing what they’re getting, says Giovanna Mozzo, co-director of The Hub, a behavioral health organization serving southwestern Connecticut. They don’t know that they’re taking fentanyl—and that it can kill them.

While fentanyl is much more powerful than heroin, gram for gram, it’s also much cheaper. That’s because the drug is synthetic rather than produced from poppies. “It’s chemistry, not crops,” says Robert F. Lawlor Jr., drug intelligence officer for Connecticut with New England HIDTA (High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas).

China and Mexico are the primary sources of illegal fentanyl, but it’s also mixed in the United States. The drug can be ordered via the internet and shipped by traditional mail.

Wrap it all together and fentanyl requires much less time, labor and investment than heroin. “On the streets of New Britain, you can buy a bag of fentanyl for $3, and you can get a fatal dose for $6. It’s as cheap as a Happy Meal,” says Dr. Charles Atkins, medical director for Community Mental Health Affiliates, which provides addiction services across central Connecticut.

Steve Hamm Photo.

Lisa Deane lost her son Joe to a fentanyl overdose last December. She was speaking at the State Capitol in support of a bill that would reclassify fentanyl as a narcotic.

A top priority for opioid experts is supplying naloxone, the opioid antidote, not only to police, emergency rooms and EMTs, but also to people who abuse drugs. Outreach workers urge people to avoid taking drugs alone and to make sure there’s naloxone nearby, so they can be revived quickly if they overdose.

Some parents of overdose victims are also critical of abstinence programs. They say these approaches rarely succeed, and, as a result, many people delay getting the help they need. Dita Bhargava, who unsuccessfully ran for state treasurer in 2018, lost her son, Alex Pelletier, to a fentanyl overdose in a so-called “sober house.” She says the treatment provided for him there was not appropriate. “It’s gross negligence,” says Bhargava, who is now a Connecticut ambassador for Shatterproof, a national drug addiction advocacy organization.

Reflecting the urgency of the problem, U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal organized an emergency gathering in Hartford on June 10, summoning political, law enforcement and health care leaders from across the state. “We need public outrage and outcry,” he urged the group. “It’s time for action.”

TheHub.org Photo.

Giovanna Mozzo, co-director of The Hub, a behavioral health organization serving southwestern Connecticut.

Blumenthal is one of the co-sponsors of the bi-partisan bill the Comprehensive Addiction Resources Emergency Care Act, which would set aside $100 billion over the next 10 years to support opioid addiction programs. But he believes that amount isn’t nearly enough to counter fentanyl, which was developed by the pharmaceutical industry to deal with pain. “This country has to invest in solutions to the root causes of the problem—in prevention and treatment,” he says.

Here are some of the new initiatives aimed at dealing with the rise of fentanyl:

• The state has expanded medication-assisted treatments in jails and prisons, targeting people who are vulnerable to overdosing on fentanyl when they’re released from lockup.

• Federal authorities have warned of fentanyl’s risk during outreach to 50,000 Connecticut students in 164 high schools.

• Pilot programs have been launched that pair community outreach workers with doctors to provide care where people are rather than expecting them to go to a clinic.

One of those programs is in New London County. Ledge Light Health District teamed with Alliance for Living, a health services agency, and hired street-wise recovery navigators to help people with opioid use disorder. The district started with three part-timers last year, focusing on New London, and now it covers the entire county with five full-time navigators.

But they noticed a critical gap. It could take weeks to get an individual started on medication. So now they’re piloting a new approach. Dr. Paul Joudrey, an internist at Yale School of Medicine, drives out into the community with navigators: When someone agrees to begin treatment, Joudrey writes a prescription and the navigators take them to a pharmacy so they start right away.

One of the navigators, Trisha Rios, lost her best friend to a fentanyl overdose, so she’s determined to save lives. In May she revived a woman who had overdosed by administering naloxone. The woman refused further treatment from EMTs, but later she sought out Rios and asked for assistance. That gives Rios hope. “I work with people who are homeless and jobless. They’re so broken,” she says. “But we can help them.”

Resources:

How We Can Help: Brochure for a state program for individuals and families: https://www.ct.gov/dmhas/lib/dmhas/publications/how_can_we_help.pdf

The LiveLoud campaign: A state web site with in-depth information about opioid use disorder: https://liveloud.org/

The Women’s REACH program: Training women as recovery navigators: https://www.ct.gov/dmhas/cwp/view.asp?a=2902&q=607228

Steve Hamm, the writer of this article, is developing a feature-length documentary about fentanyl–its impact on individuals, families and society. If you or someone you know might be willing to participate, please contact Steve at stevehamm31@hotmail.com.