With physicians’ compensation from pharmaceutical and medical device companies under increasing scrutiny, payments to doctors in Connecticut for consultant work rose to $8.5 million in 2017, up from $8 million in 2016.

Payments for meals, travel and gifts also increased from $3.2 million in 2016 to $3.5 million in 2017, data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services show.

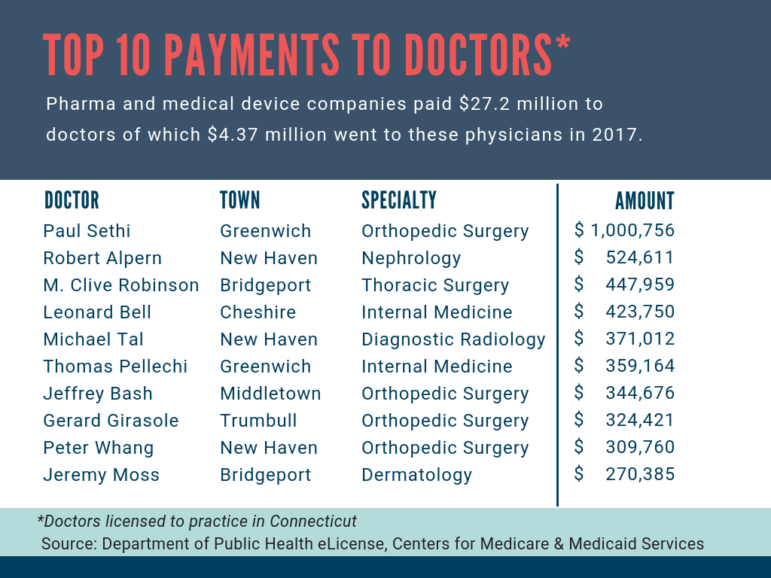

Of the total $27.2 million in payments, $4.37 million – or 16 percent – went to 10 doctors holding licenses in Connecticut.

The highest paid doctor was Dr. Paul Sethi, an orthopedic surgeon in Greenwich, who accepted slightly more than $1 million in 2017 in royalty fees, consulting work, and other services from several companies, including Arthrex Inc., and Pacira Pharmaceuticals Inc., maker of Exparel. The drug, Exparel, is marketed as an alternative to opioid painkillers post-surgery. Sethi frequently takes to Twitter to promote the use of a non-opioid alternative and is listed on the Pacira website in a case study. He did not respond to C-HIT’s request for an interview.

The highest paid doctor was Dr. Paul Sethi, an orthopedic surgeon in Greenwich, who accepted slightly more than $1 million in 2017 in royalty fees, consulting work, and other services from several companies, including Arthrex Inc., and Pacira Pharmaceuticals Inc., maker of Exparel. The drug, Exparel, is marketed as an alternative to opioid painkillers post-surgery. Sethi frequently takes to Twitter to promote the use of a non-opioid alternative and is listed on the Pacira website in a case study. He did not respond to C-HIT’s request for an interview.

Dr. Robert Alpern, dean of the Yale School of Medicine, received $524,611 for his work as a director on the boards of Abbott Laboratories and AbbVie Inc. Alpern said that he does not provide paid lectures, does not speak for the pharmaceutical companies, does not see patients or write prescriptions, and that his work on the boards is “fully disclosed to Yale University and Yale New Haven Hospital.”

“I recuse myself from any decisions related to either of these companies,” Alpern said.

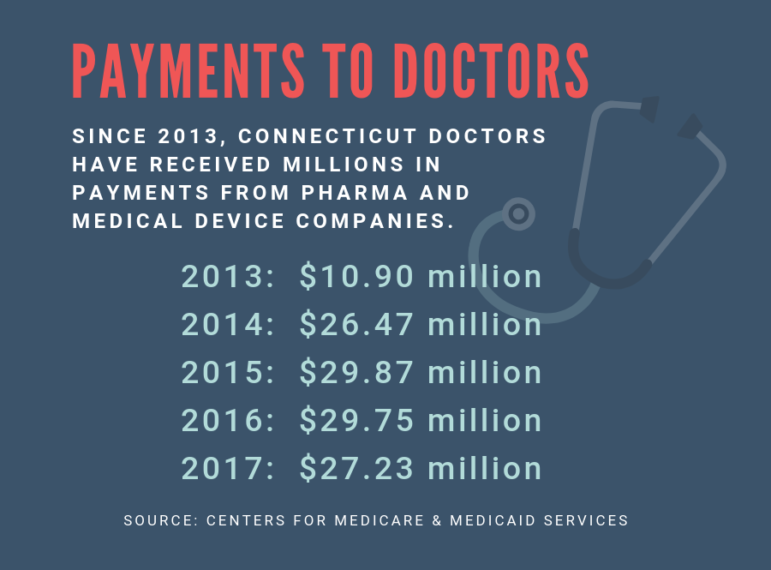

The financial relationships between pharmaceutical and medical device companies and doctors, as well as teaching hospitals, have been disclosed since 2013, under the Affordable Care Act. The law is intended to provide transparency into the business connections between health care providers and the industry.

The law is also driving some doctors—like infectious diseases specialist Dr. Roger Echols of Easton—to give up their license to practice medicine. “It’s why I did not revive mine last year,” he said, referring to 2016.

Echols was paid $526,881 in 2017 for his work as a consultant primarily for Japan-headquartered Shionogi & Co., best known as the maker of the cholesterol drug Crestor. Echols said he stopped seeing patients and prescribing medication years ago, when he transitioned to the pharmaceutical industry.

Even practicing doctors, Echols said, are now declining payment when they meet with him to discuss drug research. “They’ve gone so far that they won’t even allow us to provide a bagel or a cup of coffee at a meeting because that has to be reported.”

Overall, non-research payments to Connecticut doctors fell 8 percent from $29.7 million in 2016 to $27.2 million in 2017, the data show. Much of the decline occurred in royalty and license fees on sales of drugs and medical devices, charitable contributions, and ownership or investments in companies.

In research payments to Connecticut doctors, pharma and medical device companies paid $901,196 in 2017, down from $1.1 million in 2016, according to the data.

Nationally in 2017, doctors were paid $2.82 billion by 1,525 pharma and medical devices companies. Research payments totaled $4.66 billion.

Dual Role Of Doctors

The dual role of doctors as providers of health care to patients and marketers for drug and medical device companies has been scrutinized for several years and has been the subject of extensive research.

One report, published in a medical cancer journal that examined several studies concluded, “All the money and attention drug representatives shower on doctors has its intended effect: building relationships with doctors and ultimately changing how they prescribe.”

A study published in October 2017 by the U.S. Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; found that gifts from pharmaceutical companies result in higher drug costs: “More prescriptions per patient, more costly prescriptions, and a higher proportion of branded prescriptions.”

A study published in October 2017 by the U.S. Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; found that gifts from pharmaceutical companies result in higher drug costs: “More prescriptions per patient, more costly prescriptions, and a higher proportion of branded prescriptions.”

“There is strong evidence that pharma payments are associated with higher prescribing of the promoted medications, and with higher costs,” said Ellen Andrews, executive director of the Connecticut Health Policy Project.

Dr. Bruce E. Strober, a professor of dermatology at UConn Health, said, “Nearly all my colleagues—anybody who is a specialist in the field—do speak for drug companies, and I am compensated for my time, yes. Unequivocally, it does not alter my prescribing habits.”

Strober received $174,279 in 2017 primarily in consulting fees from Eli Lilly and Co., Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Sanofi Genzyme, Novartis Pharma AG and Amgen Inc., among others. In 2016, the latest year on record, Strober made out 61 prescriptions for Amgen’s Enbrel amounting to $239,996, according to a C-HIT analysis of Medicare Part D data. The same year, Amgen paid him $17,000.

Many doctors see their role as merely educating their peers, and being compensated for their time and expertise.

Dr. Mark Milner, an ophthalmologist in Hamden, received $186,125 in 2017 primarily in consulting and speaking fees from pharma companies specializing in dry eye, including Allergan Inc., maker of the blockbuster drug Restasis.

“There is nothing unethical if I am paid for my time. I give a comprehensive dry eye lecture whether I’m sponsored by Allergan, or Shire [North] or Bausch [formerly Valeant],” Milner said.

Dr. Steven Thornquist, a Waterbury-based ophthalmologist and former president of the Connecticut State Medical Society (CSMS), said, “The onus is on the individual physician to be ethical. I don’t think patients should give their doctor the third degree.”

It’s a fine line. Dr. Claudia Gruss, CSMS president, said physicians should decline a cash gift. “At the same time, there are certain physician experts that other physicians look up to, and educational events allow a very frank interchange between physicians in the field. We don’t want to decrease productive collaboration.” In 2017, Gruss received $120.94 in the general category – the category includes food and beverage at medical conferences.

Dr. Niranjan Sankaranarayanan, a nephrologist in Bloomfield, does not accept money for consulting and speaking engagements from pharma companies, though he did earlier in his career. “I was naïve. They invited me to talk about a medication that I was already prescribing, but after one or two talks, I didn’t feel comfortable,” he said. “This is a gray zone. They entice you with more and more, and there is no ceiling to this,” Sankaranarayanan said. He received $201.60 in general category in 2017.

Medical ethicists say the public must know that their physicians very often have complex interests. “Medicare has databases but more research needs to be done on incentives ad kickbacks,” said Dr. Howard Forman, a Yale professor of diagnostic radiology, economics and public health, who often speaks about medical ethics.

“We have to prove cause-causation rather than correlation. It’s pernicious how the money flows,” said Forman.

Marie K. Shanahan designed the graphics for this report.