At the Fresh River Healthcare nursing home in East Windsor, the chance that a short-stay patient will end up back in the hospital within 30 days of arriving at the facility is less than eight percent.

Meanwhile, 12 miles away at the Greensprings Healthcare and Rehabilitation nursing home in East Hartford, more than a third of patients who came from hospitals will be readmitted in 30 days.

The wide swing in nursing home patients’ re-hospitalization rates has a lot to do with the condition patients are in when they are discharged from inpatient stays, as well as the planning that goes into the transition to other care. The federal government has been penalizing hospitals since 2012 for high rates of patients returning within 30 days of discharge.

But now, nursing homes (or skilled nursing facilities) also are being held accountable for hospital readmissions. The federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has started publicly reporting the rates at which nursing home patients return to the hospital – for any reason — within a month of admission.

Starting in October 2018, facilities with high re-hospitalization rates will be penalized, with CMS withholding two percent of Medicare reimbursements and redirecting some of those funds to higher-performing facilities.

The new measure is stirring concern among skilled nursing providers, who say their patients are being discharged from hospitals earlier, with more acute medical needs.

CMS officials, meanwhile, say nursing homes are being rated on the measure because high, costly readmissions may indicate that the facilities are not properly assessing or caring for residents who come from hospitals.

CMS officials, meanwhile, say nursing homes are being rated on the measure because high, costly readmissions may indicate that the facilities are not properly assessing or caring for residents who come from hospitals.

Matthew Barrett, president of the Connecticut Association of Health Care Facilities, said nursing homes have known that the readmission penalties were coming for several years and have been working with hospitals to improve communication around patient transitions.

But he noted that the focus on re-hospitalizations comes at a time when nursing homes are under increasing pressure from insurance payers to reduce lengths of stay.

“One big concern is, the pressure on length of stay and discharging people quickly works against the goal of preventing readmissions,” he said.

He noted that some facilities care for older, sicker, or more high-risk patients than others.

CMS officials said the reported readmission rates are adjusted for patient age and gender, principal diagnosis in the prior hospitalization, comorbidities and other health status variables.

Readmission data from 2015 is now recorded on CMS’ Nursing Home Compare website, which uses a “five-star” evaluation system to rate the quality of each nursing home.

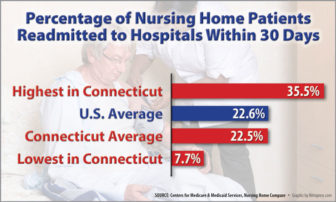

On average, the state’s homes reported a hospital readmission rate of 22.5 percent – almost equal to the national average of 22.6 percent.

The percentage of Connecticut nursing home patients successfully discharged to the community – meaning they went home within 100 days and remained there for at least 30 subsequent days — was 58.7, slightly higher than the national rate of 56.9 percent.

But the data show that while some homes rarely have residents readmitted to hospitals, others see a third of their residents return within 30 days. Seventeen Connecticut nursing homes had readmission rates of more than 30 percent in 2015, while 13 had rates lower than 15 percent.

The five homes with the lowest readmission rates were: Fresh River in East Windsor (7.7 percent); Portland Care & Rehabilitation Center (9.4); Watertown Convalarium (9.8); Fairview in Groton (10.5); and Bridgeport Health Care Center (10.5).

The homes with the highest rates were: Greensprings (35.5 percent); Apple Rehab West Haven (33.4); Miller Memorial Community in Meriden (32.9); Chesterfields Health Care Center in Chester (32.8); and Touchpoints at Farmington (32.8).

Patricia Quinn, who recently became administrator at Greensprings, said the facility is making myriad efforts to reduce avoidable re-hospitalizations, including adopting a national program called INTERACT (Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers). The state’s Medicare quality consultant, Qualidigm, has helped to train nursing homes in INTERACT, which is designed to improve the early identification and assessment of changes in residents’ health status.

Many of Greensprings’ patients have clinically complex conditions, or co-morbidities, including mental health disorders, Quinn said. Nurses and other staff are working to make sure those issues are identified early and monitored, so that patients are not sent back to the hospital for conditions that can be treated in-house, she said. Part of that effort involves educating families.

“Often with spouses and families, when there’s a change in condition, they want to send their loved one back to the hospital, not realizing that today’s skilled nursing staff can deal with that situation,” Quinn said.

She said the facility is working more closely with hospitals on care plans, and that staff conduct “root cause evaluations” when any patient is re-hospitalized for questionable reasons.

Ed Baker, newly named administrator of Miller Memorial, said that while he did not have detailed information on the home’s readmissions, nursing homes generally are dealing with patients with more serious medical needs.

“Where they used to stay in the hospital a week or 10 days, now hospitals are discharging patients much earlier, and they’re coming in with a whole host of medical issues,” he said. “We’re really in the position of providing sub-acute care.”

James Christofori, administrator at Fresh River, said the facility has worked hard to prevent avoidable readmissions by improving the post-acute nursing care it offers and adopting INTERACT. He said the home has expanded its use of physicians and APRNs (advanced practice registered nurses), focusing on infection prevention and careful antibiotic use.

“All this results in more timely and accurate assessments… and excellent resident outcomes,” he said.

Past studies have found that as many as two-third of re-hospitalizations are potentially avoidable, meaning residents’ conditions could be managed outside of a hospital. A 2016 study led by Florida Atlantic University found that one in five hospital transfers occurred within six days of nursing home admission, indicating “clinical instability” of the patient or inadequate communication. Only one-third of the transfers were preceded by an on-site evaluation by a physician, nurse or physician assistant. Family or patient insistence was a factor in 16 percent of readmissions.

Another recent study led by Indiana University noted that financial pressures have reduced the length of hospital stays and led to discharges of people with more acute medical conditions to nursing homes. It also suggested that adding penalties could “create perverse incentives for prolonged (nursing home) stays.”

Readmissions within the 30-day window are counted regardless of whether the patient is readmitted to the hospital directly from the nursing facility, or has returned home.

At the same time, a recent Yale School of Medicine study suggests that the readmission penalties imposed on hospitals are working. That study found that hospitals that were penalized with reductions in Medicare reimbursement had more significant decreases in readmissions than those weren’t cited. The study noted, however, that readmission reductions plateaued after initial sharp declines.

Nationally, 45 homes had re-hospitalization rates of less than five percent, while five homes – in Missouri, Kansas, North Carolina, Minnesota and Illinois – had rates topping 50 percent.

Policy makers have targeted re-hospitalization rates in recent years as a way to reduce Medicare costs. A 2013 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that one-quarter of all Medicare nursing home patients were admitted to hospitals in 2011, at a cost of $14.3 billion. Medicare spent an average of $11,255 per stay for a nursing home resident – 33 percent more than the average for all Medicare patients.

The OIG report found that for-profit facilities generally had higher hospitalization rates than non-profit or government-owned nursing homes.