More Connecticut doctors, therapists and psychologists are turning to the practice of mindfulness to help treat depression, anxiety, chronic pain and even addiction.

The practice — which cultivates an awareness of the present moment and an acceptance of the feelings and emotions that come with it — has reached the mainstream and is being adopted by new fields.

Veterans groups are using mindfulness and yoga as a healing tool. Teachers in some Connecticut elementary schools have incorporated it into their classrooms to help students focus. And universities are offering mindfulness training to help students deal with stress.

Today, about 600 studies on mindfulness are published annually, according to Dr. Judson Brewer, the director of research at the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts. The Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awards millions of dollars in grants for mindfulness research. The Center’s total budget has more than doubled, to $124 million, since 1999.

In September, the NIH directed $4.7 million for studies at Brown and Harvard universities and UMass to gauge whether mindfulness interventions improve medical regimen adherence, including regimens for weight loss. Physicians at Yale University are studying the use of mindfulness meditation in chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia in adolescents.

Researchers analyzing findings of past studies have found small but consistent positive effects from mindfulness, which has its roots in Buddhist philosophy. Two recent meta-analyses—one published in 2013 by researchers in Israel, and one published in 2014 by Johns Hopkins University researchers—found benefits in pain management, anxiety and depression.

“It’s exciting that the science is catching up with all this, because this is the wisdom of the ages,” said Lisa Berzins, a Connecticut Valley Hospital psychologist who uses mindfulness to counsel clients who have been through trauma.

Connecticut has seen the emergence of new mindfulness centers and meditation groups. A group called New Haven Insight offers regular meditation meetings in New Haven and Hamden, and a new mindfulness center, Copper Beech Institute, opened in West Hartford in 2014.

In response to its growing popularity, the Capitol Region Education Council (CREC) and Central Connecticut State University hosted a Mindfulness Conference in December, bringing together more than 165 educators, psychologists, doctors and therapists.

“Mindfulness teaches a lot about attention, curiosity, attentiveness — all those things that are foundations to learning,” said Emily Rosen, an educational technology specialist at CREC who helped organize the conference.

Meditation session at Copper Beech.

The Science

Scientific, peer reviewed studies on mindfulness and its health effects started getting published in the early 1980s.

The continued practice of mindfulness meditation actually changes the parts of the brain that deal with attention, body awareness and emotional responses, according to a meta-analysis published in the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science in 2011. For example, people practicing mindfulness have more activity in an area of the brain associated with positive emotions.

Individual studies and trials on the topic vary. Some, such as one published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology in October, found that while mindfulness was helpful at preventing depression relapse in patients, it was no more effective than music therapy, physical activity and nutrition training was for those in a control group.

Brewer, who has been meditating since he started medical school, said he realized during his residency at Yale that mindfulness could help those with addiction.

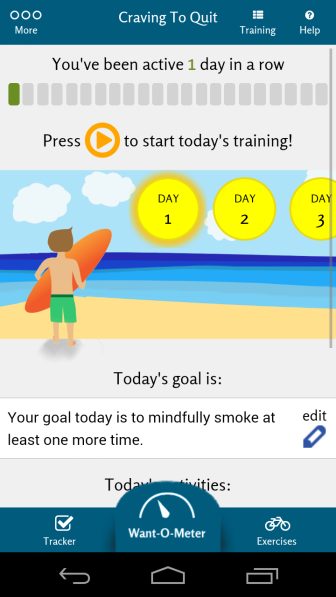

Brewer developed a smoking cessation app, Craving to Quit, in 2013, while an assistant professor of psychiatry in Yale’s School of Medicine, after his own research found that mindfulness training was more effective than other treatments in helping people overcome cocaine addiction.

“I wanted to see if we could use this to work with the hardest addiction,” Brewer said of his shift in focus from cocaine to cigarettes.

Brewer and other researchers at Yale conducted in-person trials comparing people trying to quit smoking using mindfulness techniques to those who used the standard American Lung Association smoking cessation program. The research, published in 2011 in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, found that those using mindfulness training had a greater rate of reducing smoking, and kept those gains for longer than those in the traditional program.

“It was five times as good as the gold standard a month later,” Brewer said. “That was eye opening to me.”

Craving To Quit app.

Now, Yale’s Student Wellness department is subsidizing the cost of Brewer’s mobile application Craving to Quit for all students looking to quit smoking, as the university transitions to a tobacco free campus. According to Lisa Kimmel, senior wellness manager at Being Well at Yale, 16 students have signed up since the initiative was announced in October.

Mindfulness In Action

Mindfulness can be practiced during everyday scenarios—such as when the Craving to Quit application asks users to mindfully smoke, accompanied by an audio recording guiding the process.

“Feel the texture, the weight of the cigarette,” a female voice says on the recording. “Look closely at the paper, the colors. Smell the cigarette. What does it smell like?”

At the University of Hartford, Peter Oliver, an associate professor of educational psychology, is using mindfulness in his Stress and Stress Management course, hoping to give students the skills of impulse control and the ability to respond appropriately to stress.

In one exercise, Oliver has students pile their cell phones in the center of the room with the volume turned up. Then they focus on their physical and emotional reactions as notifications start to chime without immediate access to check the phone.

“Being stressed is a very different experience than being aware that I’m stressed,” Oliver said. “Then with that awareness, I can begin to generate choices.”

Mindfulness also can be practiced as more formal meditations, as shown by 50 people who gathered for silent mindfulness meditation recently at the Copper Beech Institute.

Michael Riley, 59, of Bloomfield, regularly attends the Copper Beech meditations. An Air Force veteran suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Riley said his life has changed since he started using meditation to cope with the symptoms.

“I was afraid,” Riley said. “I was using my anger to cover my inability to deal with the fear.”

Riley said he is now able to control his impulse to respond to stressful situations with aggression, as he used to do.

“My whole world has changed now,” Riley said.

The Paradox

While the science suggests mindfulness can help with a variety of health issues, proponents say the goal is not to simply meditate away problems.

“What we learn in mindfulness is this paradoxical wisdom,” said Brandon Nappi, the executive director of Copper Beech. “We are much more able to manage our pain when we let go of this agenda of needing to manage this pain.”

Jodie Mozdzer Gil Photo.

Psychologist Lisa Berzins uses mindfulness to counsel clients.

Compassion is key to Berzins’ therapy group at Connecticut Valley Hospital, a state hospital for people with mental illness. Berzins leads a meditation in which clients focus on a situation that caused them distress, then pay close attention to their physical sensations, as well as their breathing.

Berzins then asks them to put their hands over their heart and repeat phrases of self-compassion, such as “May I be kind to myself.”

“It’s sort of instinctive that people want to push bad feelings away,” Berzins said. “Mindfulness and self compassion are sort of the exact opposite. All feelings are welcome, even the ones that really hurt.”

“Pain is inevitable in life,” Berzins said. “But suffering is pain plus resistance to it.”

C-HIT Writer Lisa Chedekel contributed to this report.