On its website, the Tumble Bugs Day School in Norwalk boasts a “highly experienced, nurturing” staff who serve infants and toddlers in a “stimulating setting.”

But a review of state Department of Public Health records shows the child care center has had numerous complaints and citations in recent years for lapses in supervision that have injured and traumatized young children.

In 2010, the center failed to notify parents when a balancing board fell on a toddler. The same year, DPH cited the center for failing to take action against a staff member who restrained a toddler on a cot by “holding down his head and body” and then falsely reported that a scratch on the boy’s face was an accident.

Jordan Harrison Graphic

Then, in 2011, two children came forward to report that a preschool teacher had sexually abused them during naptime – an allegation that led to the April 2012 arrest of a 44-year-old Harold Meyers, who worked at the center in 2008 and 2009. DPH investigated the case last year, but determined that the center had made oversight changes and that no further action was needed.

Soon after, DPH was summoned again – this time on a complaint from parents that their 15-month-old son was bitten by other children on three separate occasions, without them being notified.

Despite the multiple safety violations, DPH has allowed Tumble Bugs to remain open, with minimal consequences.

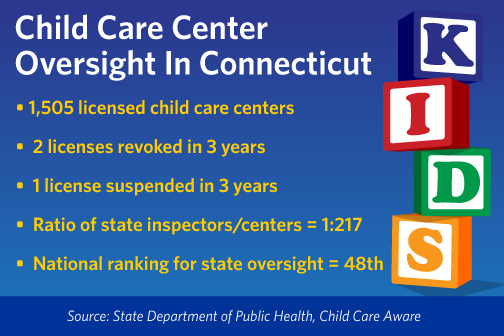

The situation is not unusual in Connecticut, where child care center license revocations are rare and oversight is lax. In the last three years, DPH has revoked only two center licenses out of the 1,505 centers in the state – a far lower rate than other states.

A review of two-dozen cases handled by DPH indicates that providers are routinely allowed to continue operating after repeated health and safety violations, including abuse.

The lack of strong enforcement is consistent with the findings in a 2013 national report that places Connecticut child care center oversight in the lowest five percent of states. Connecticut was ranked 42nd overall, and 48th in oversight, in a national ranking by Child Care Aware of America, a leading child care advocacy group. The rankings are based on benchmarks related to program requirements and oversight.

Connecticut is one of only nine states that do not conduct at least yearly inspections of child care centers; one of six states that do not require any initial health and safety training for providers; and one of four states that do not require program directors to have at least a high school diploma or GED.

Unlike 23 other states, Connecticut does not require that background checks of child care staff include a check of the sex-offender registry.

Even in an area where Connecticut meets national recommendations, concerns have been raised. A state audit in October found that the DPH was not verifying that the required criminal background checks were being done on all child care employees – posing a risk that children were coming into contact with “unsuitable individuals,” the auditors said.

While Connecticut has some of the best teacher-to-child ratios in the country, the approach to oversight has been “lackadaisical,” said state Sen. Beth Bye, D-West Hartford.

“We have these very good standards — but then we don’t monitor them,” said Bye, a longtime advocate for quality child care. While certain school readiness programs are held to high quality standards, she added: “If the average parent walked through a lot of day care centers, I don’t think they’d be thrilled.”

The DPH inspects child care centers once every two years – far less frequently than the Child Care Aware of America recommendation of quarterly inspections. The national report also shows that Connecticut’s inspection caseload is the third highest in the country: The ratio of one inspector to 217 cases is triple the caseload recommended by the National Association for Regulatory Administration (NARA), which directs a maximum average workload per inspector of 50 to 60 child care facilities.

While many states have increased inspections in recent years, Connecticut’s caseload has risen by 24 percent since 2011, data shows.

Although Connecticut ranks better in regulating smaller family daycare homes, a recent federal audit of 20 such homes found significant lapses in health and safety oversight of those licensees, as well.

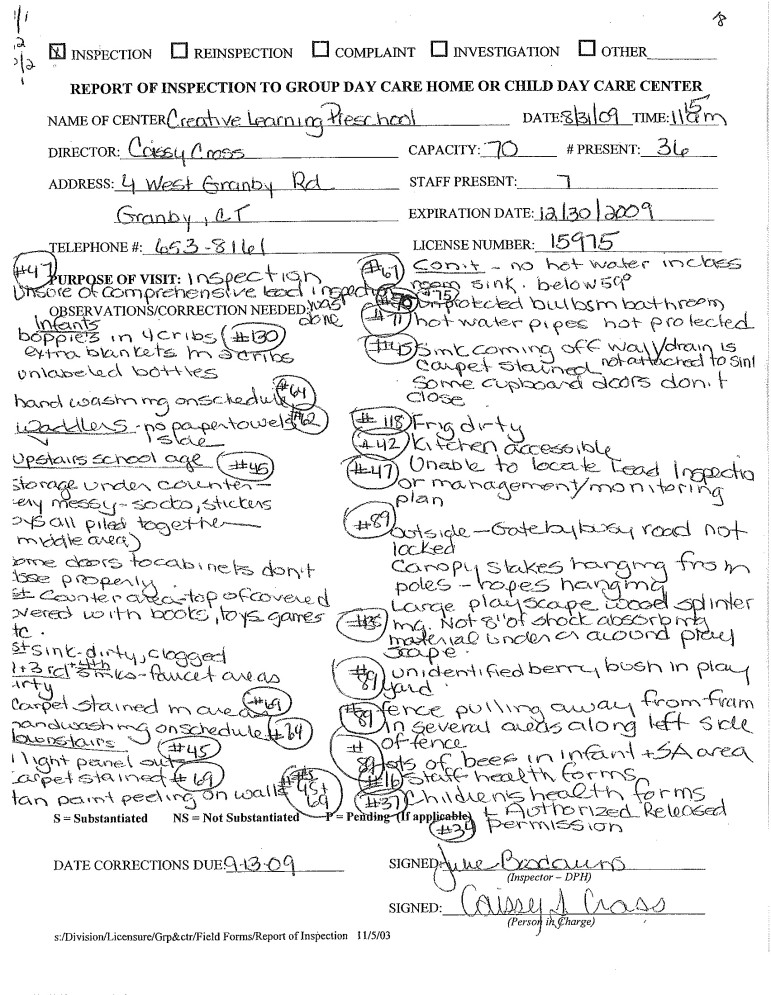

2009 Creative Learning Preschool and Child Care inspection report.

A review of Connecticut’s enforcement actions in the last three years shows that fewer than 1 percent of child care centers lost their licenses because of revocation, suspension or voluntary surrender, and less than 3 percent were subject to DPH consent orders, the strongest form of discipline, when violations were found. Only two of Connecticut’s 1,500 licensed centers (.13 percent) have had their licenses revoked in the three years; another 10 centers (.6 percent) voluntarily surrendered their licenses.

In contrast, Oklahoma’s Department of Human Services revoked 33 of 1,666 center licenses from 2010 to 2012 – 15 times the rate of Connecticut. Similarly, North Carolina revoked 37 center licenses and suspended seven others in the past three years – six times the rate in Connecticut. And the Florida Department of Children and Families revoked 44 of 4,700 child care facility licenses in just the last two fiscal years – or seven times Connecticut’s rate.

Oklahoma, which ranks 2nd nationally in child-care center oversight, has 104 field inspectors for child care; Connecticut has a total staff of 25 for a similar number of centers.

Nick Vucic, senior government affairs associate for Child Care Aware, said weak oversight guts strong program standards. In many states, oversight has been strengthened after a child care death or tragedy.

“It’s a reactive type of system. You leave it open for these incidents to occur — and when they do, that’s when you see states adopt changes,” he said.

Vucic said that while some oversight improvements cost money, many are simply policy decisions — such as requiring that providers be trained on topics such as child abuse and child development.

“It’s almost always more of a policy decision than a financial decision,” he said. “The states that do more usually have strong advocates in this area.”

Connecticut’s oversight system hasn’t changed since 2009, when a report by the Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut found an “alarming number of significant health and safety concerns” at child care centers, weak oversight and inconsistent reporting by inspectors. Of the state’s monitoring system, the report said, “It is uncertain what the criteria are for re-inspections and the extent to which remedies are put in place.”

State officials said they are working to strengthen both program quality and monitoring. A new Office of Early Childhood will take over the licensing of facilities from DPH next year.

The state was counting on a federal “Race to the Top” grant to fund improvements to child care quality and to launch a quality-rating system that would grade providers on a four-tiered scale. But Connecticut lost out on the grant last week. In its proposal, the state had proposed to add 16 more inspectors, increase inspections to once a year, and make unspecified “regulatory and policy changes to improve licensing requirements.”

The state still plans to pursue a quality-rating system, but similar systems in other states have taken years to develop.

Myra Jones-Taylor, director of the Office of Early Childhood, could not be reached for comment. But DPH officials said that for now, they are doing the best they can with the rules and resources they have.

“DPH supports increased monitoring of licensed child care programs to improve regulatory compliance … (and identify lapses) before children are negatively impacted,” said Bill Gerrish, a spokesman for the agency. Similarly, DPH supports increasing training and education for providers, which Gerrish said would require legislative action.

On enforcement, he said the agency uses a number of methods, such as consent orders and corrective action plans, to protect children and ensure compliance with regulations.

Enforcement Actions Rare

The two Connecticut child care centers that have had their licenses revoked were smaller centers – Cookie Club in Wallingford, a group daycare, and Colorful World Child Day Care in Bridgeport.

Cookie Club’s license was revoked in June 2012 after repeated DPH citations for lapses in supervision and safety, including hazards such as unlocked toxins and rusty swings, and inadequate record keeping.

DPH revoked Colorful World’s license in 2011 after finding violations deemed “threatening, neglectful…or frightening treatment” of children, including a young child who was left outside alone in the cold with no coat or shoes. Records show that DPH had given Colorful World’s operator conditional approval to open the center in August 2010, despite having revoked her family day care license in 2007 because of “numerous violations.”

Yet a review of records indicates that other centers with similar violations have been allowed to continue operating. Usually, DPH opts to impose fines and require centers to hire consultants and do training.

Tony Bacewicz Photo

Tumble Bugs Day School was cited multiple times for violations from 2007-10.

Tumble Bugs of Norwalk was cited multiple times by DPH from 2007 to 2010 for violations including inappropriate discipline, failure to report abuse, excess group sizes and indoor hazards. But DPH did not issue a consent order until February 2011. The order, which cited the center for the incidents including holding down the toddler and group size violations, carried a $4,000 fine and required that the center hire consultants and conduct staff training.

The owner of Tumble Bugs did not respond to requests for comment.

Other examples of centers with repeat violations include:

• Creative Learning Preschool and Child Care in Granby was cited repeatedly from 2003 to 2008 for violations including unsanitary and unsafe conditions, such as a “moldy” playhouse, and poor record-keeping. In 2009, DPH learned of an incident in which a staff member yelled and cursed at a group of toddlers, called them “little asses,” and slapped a child in the face, according to records. The same staffer pulled a chair out from under a toddler and caused the child to fall and hit his head. Parents were given false information about the injury. The staff member previously had kicked a child. Other violations included leaving an infant in a jumper seat, smelling of vomit, with no socks and cold, purple feet.

The center was allowed to keep operating under a 2010 consent order that carried a $1,500 fine and required training. But in 2011, DPH cited Creative Learning again for failing to complete all of the requisite training, as well as unclean and unsafe conditions in some areas.

Owner Jeff Swanson declined comment, saying the problems were old and that “we currently run a high quality program.”

• Kiddie Kampus in Niantic was cited for multiple problems from 2005-09, including ripped furniture, poor record-keeping and disciplinary lapses. Not until 2011 did DPH impose a consent order on the center, this time for failing to report suspected child abuse and neglect by a staff member. The staffer had “handled children roughly” and sworn at them—behaviors that had been observed by “multiple staff,” records say. The center was fined $1,200 and directed to improve training. Since then, the center has been cited twice, in August 2012 and September 2013, for “child protection” issues that have required the involvement of DCF. The owner could not be reached for comment.

• DPH cited Educational Playcare in Simsbury for dozens of violations in 2008 and 2009, ranging from filthy floors, to inadequate supervision, to staff yelling at children. Inspections and complaints in 2010 and 2011 found ongoing problems. In 2012, DPH imposed a consent order, citing a staff member who aggressively grabbed a toddler in anger; employees passing infants back and forth through an open window; improper staff-to-child ratios; and other violations. The center was fined $3,000 and directed to improve training and maintenance.

Center co-owner Jane Porterfield said, “Nothing is more important to us than the safety and well-being of the children entrusted in our care every day . . . To that end, all of the issues that were raised have been addressed and resolved, and our most recent inspection resulted in a very positive review and praise from the inspector.”

• KinderCare of Shelton was the subject of at least nine separate complaints related to health and safety since 2006, records show. DPH required the center to submit five corrective action plans and imposed three consent orders for a long list of violations. The most recent consent order, in 2011, cited instances of staff members being “rough with children” and “yell(ing) in children’s faces,” as well as failing to comply with earlier consent orders, in 2006 and 2007. The center paid a $5,000 fine and pledged to correct the problems – but then was cited again in 2012 for lacking an adequate child abuse and neglect policy.

Colleen Moran, a corporate spokeswoman for KinderCare, said the Shelton center made “several leadership changes” in 2011, retrained all staff and corrected all of the violations. “We work closely with state licensing officials in every state we operate in and regularly educate our staff about promptly reporting incidents of inappropriate behavior,” she said.

Montessori School was cited for multiple violations from 2006-10.

• DPH cited the Montessori School on Edgewood in New Haven for multiple violations from 2006 to 2010. In late 2010, the center was cited for failing to report two incidents of suspected abuse to the Department of Children and Families (DCF): a staff member who had “repeatedly used excessive force” with a two-year-old girl who was “fussing” during nap time, and a worker who forcefully grabbed a child’s hand. The staff member was arrested and others were disciplined; center officials acknowledged that “administration was lax.” In a January 2012 consent order – a year later — DPH fined the center $2,000 for the failure to report and ordered staff training.

Center director Linda Townsend-Maier said last week that she believed the DPH enforcement was “tougher than it should be,” given that the center took corrective action soon after the first incident. “We did all the things we were required to do (by DPH), and more,” she said.

• Sugar Plum Nursery School in Bridgeport was cited for “numerous repeat violations” from 2001 to 2011, DPH reports show, including poor physical conditions and inadequate staff training. But not until 2011 did DPH impose a consent order on the center, for violations ranging from leaving children alone unsupervised, to inadequate record-keeping. The center was cited again in late 2011 for violating the terms of the consent order and for not abating “toxic levels” of lead found in peeling paint and playground soil. In May 2012, DPH approved a “negotiated corrective action plan” to address the problems, allowing Sugar Plum to retain its license.

An administrator at the center said the owner could not be reached.

Training Standards, Family Home Oversight Lacking

Contributing to Connecticut’s 48th place ranking on oversight are its lax requirements for initial training of child-care providers.

The state is one of a few that require only an initial orientation of providers, but no training in health and safety, discipline or child development. It does require annual training, as most states do. Child Care Aware of America recommends a minimum of 40 hours of initial training.

Connecticut is not among the 31 states that post inspection reports online, nor the 40 states that require centers to have regular communication with parents. It also does not use licensing fees to directly support licensing oversight, as many other states do.

Judith Meyers, president and chief executive officer of the Child Health and Development Institute, said state monitoring “clearly is weak,” noting that a state study is underway to review Connecticut’s licensing policies.

In addition to licensed providers, she said, there are hundreds of unregulated home day cares in Connecticut that are “outside the licensing network.”

Gerry Pastor, president of the CT Child Care Association (CCCA), said the providers’ group has been working cooperatively with the state to improve the quality of programs and the licensing process. He said CCCA supports both the review of licensing policies and the planned quality-rating system, although questions remain about how the system will be used.

In addition to child care centers, the DPH licenses and inspects family day care homes. Nationally, Connecticut ranks 15th in program requirements and oversight of family homes — better than the ranking for childcare centers. But its ratio of inspectors to programs – 1:332 – is six times the recommended level, and the third highest in the country, according to a 2012 report by Child Care Aware of America.

The state inspects family homes just once every three years; does not check staff against the sex-offender registry; and requires only minimal initial training in first aid, instead of the 24 hours of recommended training in child development, health and safety.

U.S. Office of Inspector General Photo

Safety violations were found at this center.

A recent audit by the inspector general of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services highlighted lapses in oversight, with inspectors finding that all 20 of the Connecticut homes they reviewed failed to comply with licensing requirements related to health and safety, including a lack of regular background checks and unsanitary conditions, such as dog feces in play areas.

Because the state inspects family providers infrequently, “some health and safety violations may exist up to 3 years before a state licensing inspector discovers a problem that places children at risk,” the report found.

As with child care centers, enforcement actions against the state’s 2,472 family providers are rare, records show. About one percent (28) of family homes had licenses revoked or summarily suspended in the last three years, while another one percent (34) voluntarily surrendered licenses. Fewer than one percent of family homes were subject to consent orders.

A review of records shows that family providers with repeat violations often are allowed to continue operating. For example, the DPH substantiated that Patricia Rudolph of Monroe violated child protection and supervision rules in 2010, when two young children were left alone in her home day care for at least 10 minutes while she was at a doctor’s appointment.

She was directed to complete three hours of training and ordered to pay $800, and was allowed to keep her license.

C-HIT Intern Brittany Everett contributed to this story.

To search for information on child day care centers go to c-hit’s data mine.