In 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, which abolished racial discrimination in the armed services. There was significant pushback – within and outside the military – but by the end of the Korean War, most of the armed services were desegregated.

We have not eliminated racism – not by a long shot – but Truman’s signature at least moved the ball down the field. And if the U.S. military wanted to, it could continue its tradition of being a leader of social change.

We have not eliminated racism – not by a long shot – but Truman’s signature at least moved the ball down the field. And if the U.S. military wanted to, it could continue its tradition of being a leader of social change.

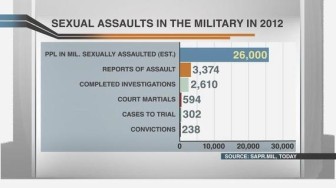

According to Department of Defense (DOD) estimates, more than 26,000 incidents of unwanted sexual contact occurred in the military in 2012, but just 238 incidents resulted in convictions.

Reporting falls far short of actual incidences. From October 2012 to last June, just 3,553 sexual assaults were reported to the DOD.

It is long past time to remove the chain of command from the prosecution of serious crimes – including sexual assault — committed by military personnel. The Military Justice Improvement Act of 2013 has the potential of ushering in a sea change in the way we deal with a social ill, with the military once again leading the way. That this piece of legislation hasn’t sailed through Congress is an indication of just how dysfunctional is the 113th.

Laura Cordes, executive director of the Connecticut Sexual Assault Crisis Services (CONNSACS), says that while sexual violence is not unique to the military, the military is “uniquely poised to address it.”

“Branches of our military operate in closed and controlled environments,” said Cordes, who in July co-authored with U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal an op-ed in favor of the act. “They are communities that embrace and promote high standards, discipline, honor and integrity. A real opportunity exists with the passage of the MJIA for all branches to blaze a trail by fully embracing a top down, zero tolerance for sexual violence, and providing victims with a way to safely report and receive support through an independent, objective and non-biased military justice system – a system worthy of the men and women in uniform.”

During legislative hearings, we’ve heard too many stories where a sexual assault – a rape – was met with indifference or worse by military commanders. People – men and women – who report sexual assaults “risk careers, the respect and support of their units, friendships, income and housing,” said Cordes.

The Justice Improvement act is an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act, and Connecticut’s other senator, Chris Murphy, supports it, as well.

“Twice Betrayed,” a recent report from the Center for American Progress, examined the authority military commanders have when a serious crime is committed by one of their troops. Unfortunately according to the report, 63 percent of the service members whose rapes were recorded in the annual (and exhaustive) Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members (WGRA) say they were raped by someone who outranked them.

The 2012 WGRA also says that the incident of unwanted sexual contact is “significantly statistically higher” in 2012 (6.1 percent) compared to 2010 (4.4 percent).

“Our heroic service men and women deserve better,” said Cordes.

Some of the discussion is reminiscent of earlier this year in what is usually a pro forma extension of the Violence Against Women Act – but not with the 113th, which has a vocal cohort that just doesn’t get it, particularly when it comes to women.

We hear platitudes about honoring veterans. Women make up roughly 15 percent of the active military. They are 200,000 strong, according to the Pentagon. November was Military Family Month.

What better way to honor than to protect them from the enemy that is often from within?