After honorable discharges from the Army in 1979, and the National Guard in 1983, Arnold Giammarco sunk into a pattern of substance abuse, shoplifting and jail before turning his life around, marrying in 2010, and becoming a father.

But the Italian-born Giammarco, 57 – one of thousands of legal residents who serve in the U.S. military, despite lacking citizenship – now counts the days away from his family in Sulmona, Italy, after immigration authorities abruptly took him from his Groton home to a detention facility in May 2011 and deported him to Italy last November. Today, (Nov. 12) Giammarco filed a lawsuit to compel the government to rule on his 1982 citizenship application, which he says was never processed.

Tony Bacewicz Photo

Sharon Giammarco and daughter Blair look at photos of their visit in Italy where they were reunited with Arnold.

Mark A. Reid of New Haven, 49, spent six years in the Army Reserve before his honorable discharge in 1990 and still speaks about being “willing to die for this country.” Now he sits in a Massachusetts jail, facing deportation to his native Jamaica because of four drug convictions including sale of narcotics and possession of heroin. Last November, immigration officers moved Reid – who came to the U.S. at age 14 — to Immigration Custody from the Brooklyn, CT jail where he was serving time for what he described as “a $30 drug sale.’’

The two men are among what veterans’ advocates say is a growing number of noncitizen military veterans who are being deported for crimes for which they served time years earlier.

Giammarco moved to the U.S. at age 4. His deportation came 16 years after his larceny convictions, nine years after his drug convictions; Reid’s came two years after his last conviction. Unlike citizen veterans who run afoul of the law, non-citizens’ punishments don’t always end with convictions and incarceration, and the military that once embraced them as equals does not always intervene on their behalf when immigration officials move to deport them.

“There’s a mismatch between the claims of the [Obama] administration in focusing on dangerous criminal aliens, and people who have been deported,” said Michael Wishnie, a Yale University law professor and supervising attorney of the Yale Law School clinics that are representing Giammarco and Reid pro bono.

“Our veterans should be celebrated and not arrested and deported, and particularly not for low-level offenses,” said Wishnie.

Since 1996, the list of crimes that make a noncitizen eligible for deportation has been expanded and includes minor offenses, Wishnie said.

While the federal government does not break down its criminal deportation statistics based on whether deportees are veterans, advocates such as Craig R. Shagin, a Philadelphia lawyer who specializes in immigration law and opposes deporting veterans, say the number “is likely in the thousands.”

Legal noncitizens, known as green card holders, have served in the military throughout American history.

Khaalid H. Walls, a spokesman for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which handles deportations, said the agency is “very deliberate in our review of cases involving veterans.” He added that “any action that may result in the removal of an alien with military service must be authorized by the senior leadership in a field office, following an evaluation by local counsel.’’ Walls said that ICE issued a memo in June 2011 citing U.S. military service as a positive factor that should be considered in determining if a case should go forward.

Members of Congress have raised concerns about veterans being deported, but there has been no action on the issue. U.S. Rep. Mike Thompson (D-CA), has been unsuccessful in two attempts to get a law passed that would require the approval of the Secretary of Homeland Security before a deportation process is initiated against any noncitizen veteran who served honorably.

During a Senate Judiciary Committee Immigration hearing earlier this year, U.S. Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.) told of longtime legal permanent residents with families, steady employment and honorable service in the armed forces being deported “for any of a litany of relatively minor offenses.”

Wishnie, the Yale law professor, called it “shameful’’ that Reid has been locked up by immigration since November 2012 and a “moral tragedy’’ that Giammarco was held for a year and a half and deported. “He was rehabilitated. He was a success story,’’ Wishnie said.

‘Punishment Does Not Fit The Crime’

Giammarco, born Arnaldo, grew up in Hartford. He owned a deli, and worked in meat departments of food stores. He served in the Army from 1976 to 1979, the National Guard from 1980 to 1983, and received honorable discharges.

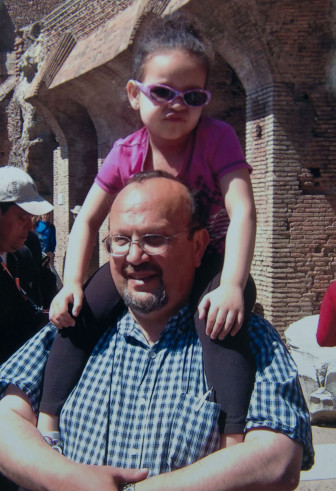

Arnold Giammarco and Blair in Italy.” credit=”

Married with a young daughter, he was taken from his Groton home to Immigration Detention where he remained for 18 months. His deportation was based on two 1997 larceny convictions, misdemeanors for which he served two simultaneous three-month sentences, and a 2004 drug conviction for possession of cocaine, for which he was not sentenced to jail.

“The punishment does not fit the crime,” Giammarco said of his deportation, which occurred years after he had reformed from being a homeless substance abuser, arrested for a string of nonviolent crimes, to a sober man with a steady job. He quit drugs, worked as a night manager at a McDonald’s, and took care of his daughter, while his wife, Sharon, went to school.

“I am asking for no special favors, just to be treated as an American who was willing to fight for his country,” he said in a statement conveyed by Sharon. “As far as I’m concerned, I’m still an American.”

Today, he lives in Sulmona, Italy in a villa owned by a distant cousin. He does landscape work on the property in return for reduced rent. He doesn’t speak Italian. He is shunned by other relatives in Italy and can’t get a job because people assume he must have committed a heinous crime for the U.S. to deport him.

Sharon works seven days a week as a case manager in mental health and alcohol and drug rehabilitation. She and their daughter, four-year-old Blair, now live with family in Niantic because she was struggling to pay rent while sending her husband money and saving to visit him in Italy. She and Blair visited him once. They Skype with him every night.

Giammarco’s parents, Lino, 91, and Elena, 84, who live in Rocky Hill, are ill and said their goodbyes to their son before he was flown out of the country, Sharon said.

Giammarco applied for citizenship in 1982, but said he never received a response. He considers his file still open. But the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service has maintained that the application wasn’t complete, according to a ruling of the Board of Immigration Appeals.

While in immigration jail, Giammarco appealed his deportation action and sought a pardon from the State Board of Pardons and Paroles. Both efforts were unsuccessful. He and his wife contacted Yale Law School for help during the summer. Students said they are researching and evaluating his legal options before deciding what action to take.

Reid Thought He Was A Citizen

Reid’s case is farther along. Yale lawyers have been working on it for the past year. It is now pending in U.S. Immigration Court in Hartford. Reid will remain in the U.S. at least until all court proceedings are exhausted, according to his attorneys.

The Yale lawyers also have filed a class-action habeas corpus suit in U.S. District Court in Springfield, MA, on behalf of Reid and all inmates being held without bond in immigration detention for at least six months, requesting that they be allowed to post bond. The suit argues that Reid’s legs, hands and feet were needlessly shackled at a hearing in Hartford Immigration Court, and asks that he not be shackled for any future hearings.

In a telephone interview from jail, Reid said that he was shocked by his deportation action because he thought he was a U.S. citizen. He said that when he joined the Army Reserve in 1984, the recruiter had told him his military service would result in automatic citizenship.

“President Obama said at his inauguration that the oath he was taking was the same oath soldiers take. So, if the oath is so important, why am I being deported from my own country?” Reid asked.

While Reid’s deportation action is based on four drug felony convictions, he has a criminal record for other non-violent misdemeanors and felonies that weren’t cited as the basis for deportation, his lawyers said.

Reid formerly owned four rental properties in New Haven, which he lost in foreclosure. While in jail, he completed a correspondence course to become a paralegal, and is taking classes in criminal and real estate law. He said if he prevails in his appeal, he wants to help others facing deportation.

“People in America are unaware of how devastating it is to be in immigration detention,” he said. “I will dedicate my life to this and bring light to what’s going on in immigration.”

Reid has a daughter who goes to a New Haven high school and a son who graduated from college and joined the Navy. His mother and sister live in Florida.

If released, Reid has been promised shelter in a New Haven halfway house and psychological services at the Connecticut Mental Health Center. The Rev. Joshua Pawelek, a Unitarian minister in Manchester, has written in support of Reid in an online blog and has helped pay for his correspondence courses.

“He did his time, he served his country — he had jobs, and has a child in the military,” Pawelek said. “It just seems like a big disconnect that even though he committed some crimes, you should deport him.’’

Pawelek acknowledged that some people are unsympathetic to Reid’s plight and responded to the online blog that Reid should be deported because “he’s a criminal and he doesn’t deserve to be here.”

But Pawelek said of Reid: “This possible deportation really, really woke him up and it’s terrified him. I think he really wants to do his life differently.”

Giammarco’s wife, Sharon, said the reaction to her husband’s plight has been positive. She has collected more than 3,000 signatures on a petition to state and federal officials, seeking his return. When she wrote about him on her Facebook page, she heard from people around the country in similar situations.

“It’s horrible. I never knew about it until it happened to me,” she said. “That’s what is so sad. It happens every day and no one knows about it.”