When Ulysses B. Hammond was diagnosed with prostate cancer, his first thought was that he could wait to deal with it. After all, the doctor said it would spread slowly.

That reaction is typical for men – especially African Americans like Hammond — and it plays a role in explaining why they have the highest cancer death rate in the United States and in Connecticut.

“It’s not deemed very macho to actually admit or discuss physical frailties,” said Hammond, chair of the board at Lawrence & Memorial Hospital in New London.

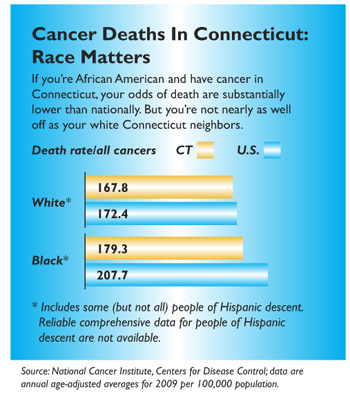

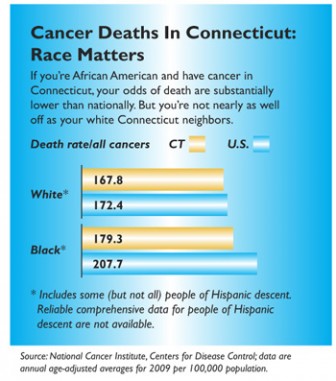

The death rate for African American men and women nationally – 207.7 per 100,000 people – is more than 20 percent higher than the rate for whites, according to 2009 data, the latest from the National Cancer Institute. Connecticut’s rate is 179.3 for blacks and 167.8 for whites.

WebKazoo Graphic

The numbers for African American men alone are even more striking. Nationally, their death rate is 274.7, compared to 209.8 for white men. In Connecticut, the rate is 230.9 for blacks and 204.3 for whites.

Narrowing gaps like this is a top priority for health policymakers here and nationally. Early efforts have seen some progress; deaths for many cancers have been falling.

“But we’re still seeing a wide range of disparities in almost every area,” said Elizabeth Krause of the Connecticut Health Foundation, which has invested almost $15 million in health equity since 1999. “We’ve really got to focus our efforts on advancing solutions.”

The motivation is more than altruism. It’s money.

When cancer patients don’t have health coverage, don’t trust physicians or won’t confront their own vulnerability, their diagnosis is late and treatment is expensive. Those delays added $230 billion to U.S. medical costs between 2003 and 2006, according to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. So the payoff for improving care – starting with prevention – could be enormous.

Policymakers, researchers and practitioners are only beginning to come to terms with the complex role that race, culture, education, income level and even biology play in determining whether a person gets cancer, how soon it’s detected and whether he or she will die.

The focus now is on strengthening public health and prevention: collaborating more effectively with community groups to break through cultural barriers, expanding health coverage, encouraging research and better data collection, and showing practitioners how their attitudes about differences affect the care their patients get.

Practitioners are looking for innovative ways to reach out to underserved people – whether it’s African American men who won’t talk about cancer, or transgendered women who don’t get routine screenings because they feel disrespected by their doctors.

“We are finally getting our act together and beginning to understand that we just can’t do things in the absence of bringing the community together at the same table. We need them. They are experts,” said Marie Spivey, vice president for health equity at the Connecticut Hospital Association and chair of the Connecticut Commission on Health Equity.

Disparities are complex. Some follow income lines that drive lifestyle choices, education and access to health care. Others are cultural. People speak different languages, have different attitudes toward health and wellness, and interact with health providers in different ways. And others are biological.

“It’s a very complicated kind of puzzle,” said Anees Chagpar, director of the Breast Center at Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale-New Haven Hospital. “All of these issues just kind of spin together.”

Why, for example, do African American women have a lower incidence of breast cancer than white women, but a higher death rate? The most recent Connecticut data show that the incidence is 118.9 per 100,000 for African American women and 139.7 for whites. The death rate, though, is 25.9 for African Americans and 21.4 for whites.

“African American women clearly have a history of issues with access to health care,” said Andrew Salner, director of the Helen & Harry Gray Cancer Center at Hartford Hospital and founding chair of the Connecticut Cancer Partnership. But there are also trust and cultural challenges when it comes to reaching African American women, he said. And they might be predisposed to a type of cancer that’s more aggressive.

But one thing is obvious, Chagpar said: insurance is a main driver of disparity. “At the most basic level, if we can provide health care evenly across the board, we have done a great service.”

Health officials say the Affordable Care Act will help by expanding coverage to more people, focusing greater attention on preventive health, and centering care on individual needs.

Health care is already moving in that direction. The William W. Backus Hospital in Norwich, for example, is matching low-income patients with primary care physicians for follow-up after they visit the Emergency Department or the hospital’s mobile care van. Another program with the NAACP brings breast cancer screenings to churches, temples, salons and senior centers.

“These kinds of collaborations and partnerships – getting people connected – those things really make a difference,” said James O’Dea, a vice president at Backus and administrator of the hospital’s cancer services program. “For the first time in my 25 years in health care, we are genuinely talking about a health care system, instead of a sick care system.”

Other examples from around the state include:

- Hartford Hospital is expanding its outreach to African American and West Indian men with a new wellness program this fall. A community leader is using his connections to build a more holistic awareness of what it means to be healthy.

- Yale researchers are analyzing how cancer develops in people of different ethnic backgrounds.

- A new community coalition is drafting a plan to reduce obesity in Bridgeport and Stratford, in part to prevent cancer. Bridgeport Hospital is coordinating the program with municipal and state agencies, community organizations and health care providers.

Despite the strides, progress can be frustratingly slow. For example, Hartford Hospital began an extensive breast cancer outreach program 20 years ago, including free mammograms for women without insurance. Only now are disparities in the stage of diagnosis and survival rate disappearing, Salner said.

Baker Salisbury, chair of the Health Equity Committee of the Connecticut Association of Directors of Health, said equity efforts must compete with discouraging socioeconomic trends. “The growing inequality of our society is hugely evident in Connecticut,” he said.

Hammond has seen the disparity issue as both a patient and health care leader. At L&M, he helped break ground in June for a $35 million cancer center in partnership with Boston’s Dana-Farber Institute. And as a cancer survivor, he’s talking openly about his experience. A vice president at Connecticut College, he opted for surgery after his initial hesitation and is doing well today.

He tries especially to reach out to fellow African Americans and Latinos because of the cultural challenges they face.

“They know that I get it,” he said. “We can communicate.”