Tameeka Coleman and six of her children lived on the streets before moving into a shelter in Fairfield. “We were together, so it was bearable,” said Coleman, 38. The hardest part was when her children cried for their home. “They wanted to know how we had lost our apartment,” said Coleman, who was evicted after she couldn’t pay the rent.

Living conditions play a key role in children’s well-being. Several studies show that parental income and their ability to invest in their offspring affect children well into adulthood. Access to health care, nutritious food and reliable transportation have a direct bearing on childhood outcomes.

Contributed Photo.

Standing outside her new condo is Tameeka Coleman surrounded by her children.

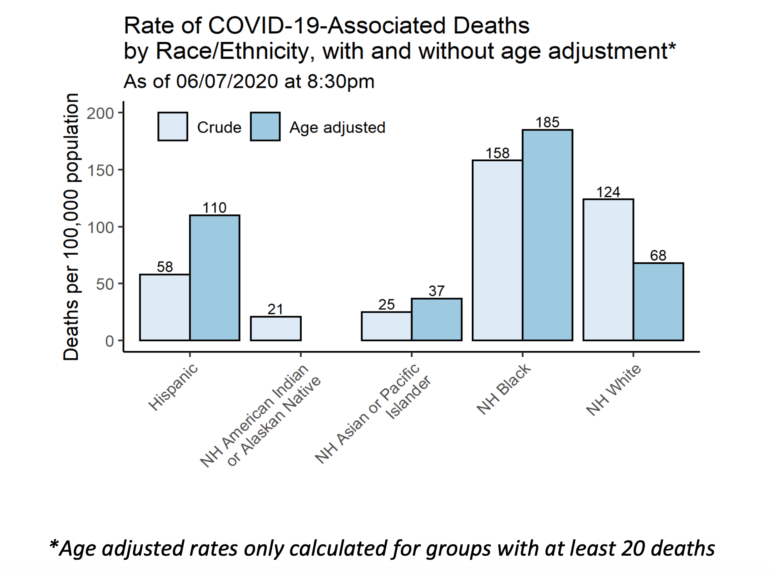

Now, new reports from the Fairfield-headquartered Save the Children (STC) and Brandeis University show that children who are already on the wrong side of the statistical divide are experiencing a higher burden from the coronavirus pandemic, which has affected blacks and Latinos disproportionately. The impact is far-reaching: from loss of shelter, household income, and access to food, to heightened stress during quarantine, and barriers to health care.

“When you talk about children, you’re talking about the adults, because children need the adults,” said Dr. Lucia Benzoni, a pediatrician with Hartford HealthCare in Litchfield. “If their parent or grandparent gets very sick and ends up in the hospital, where do the children end up? Who takes care of those children in that household?”

As with any pandemic—including tuberculosis and AIDS in the past—the stresses experienced by people of color are exacerbated and increase the risk for the most vulnerable children. The STC report, which examines how well states provide for children, shows that children living in New Haven and Hartford counties have a COVID-19 vulnerability index of 0.52 (with 1 being the highest), followed by Fairfield County with an index of 0.45. The remaining counties fared better, with Windham receiving a score of 0.42; New London, 0.36; Middlesex, 0.12; Litchfield, 0.08; and Tolland, 0.07.

“Coronavirus has a heart-wrenching impact on our nation, leaving kids further behind in communities across America,” said Betsy Zorio, vice president of U.S. Programs & Advocacy at Save the Children.

Margarita Alegria, chief of the Disparities Research Unit at the Mongan Institute, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “There’s no question that COVID is disproportionately affecting communities of color. We are seeing it in Latino communities, in Asian communities, and in black communities where they’re undergoing tremendous stress.”

Coleman, a single mother, now calls a three-bedroom condo in Bridgeport her home, which she managed to secure through the nonprofit Alpha Community Services, YMCA, Bridgeport. Currently unemployed and without a car, she takes her seven children, including her newborn, by bus and train to doctor appointments.

Contributed Photo.

Tameeka Coleman prepares dinner in her new condo.

“My mom was addicted to heroin, and I went to prison for selling drugs,” Coleman said, adding that she gave birth to her first child while she was incarcerated. Since then, she said, she has stayed on the straight path and is making efforts to get a job, while cutting hair on the side.

“I don’t have any income,” Coleman explained. “I receive food stamps, I receive medical, but I don’t receive cash.” Her rent is covered under the program for now. The uncertainty of employment, childcare and housing in the future is adding to her depression and anxiety, she said.

Coleman’s case manager, Grisselle Gonzalez, said that because of COVID-19, Coleman had been unable to see her psychiatrist. When things got too difficult, she recommended her client to a free behavioral telehealth service called Warm Lines.

To her relief, Coleman was recently able to get back to her regular psychiatrist over the phone. Meanwhile, her children receive mental health support at school when needed, Gonzalez said. Now that the kids are home, Coleman said she is their go-to person when they become stressed.

Coleman’s situation is by no means unique.

At least a third of the 1,400 women in need of assistance from the nonprofit Women & Family Life Center in Guilford have lost their jobs either temporarily or permanently as a result of the pandemic, said Meghan Scanlon, executive director.

“A lot of them were daycare workers, many were in the service industry, others were cleaning houses and buildings,” Scanlon said. “Some families have to choose between—what we’ve been trying to mitigate with our assistance—medical costs and food, or rent and food. These are individuals who are really hard-working but don’t have a lot of savings. And COVID-19 hit them really hard.”

Despite the safety nets such as the Alpha program and the Women & Life Family Center, black and Latino children in disadvantaged neighborhoods are disproportionately affected.

Despite the safety nets such as the Alpha program and the Women & Life Family Center, black and Latino children in disadvantaged neighborhoods are disproportionately affected.

A Brandeis University study concluded that children living in neighborhoods with very low Child Opportunity Scores in Bridgeport, Hartford and New Haven, had shorter life expectancies.

Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, director of the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis, explained how some children are faring worse in the pandemic, given the risk and struggles that their parents face.

In a column on DiversityDataKids.org, Acevedo-Garcia wrote, “We don’t yet have data to examine the relationship between child opportunity and the prevalence and mortality from COVID-19, but we suspect that if we could, we would see a high concentration of cases and deaths in very low-opportunity neighborhoods. We know that segregation and neighborhood inequities lead to an unfair concentration of health vulnerability in minority communities.”