I-Team In-Depth

Antipsychotic Use On The Decline In State Nursing Homes

|

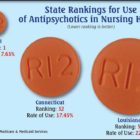

Connecticut still ranks high among states in the use of antipsychotic drugs for elderly nursing home residents, but its rate of use has dropped 33 percent since 2011 – a bigger decline than the national average — new government data show. The data released in June by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), show that nursing home residents in Connecticut, many with dementia, are still more likely to be given antipsychotics than their counterparts in 31 other states. But the state’s usage has fallen in the last 4 ½ years at a greater rate than the average drop of 27 percent, and it is now about the same as the national average — 17.4 percent. That’s down from 26 percent in 2011. CMS has been working with states for the past five years to address the overuse of antipsychotic medications in nursing homes.