The Community Health Center Inc. set up shop inside the Boys and Girls Club of Greater Waterbury on a Friday in mid-July. Armed with 24 doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, the team of six staff and volunteers sat ready for patients from 9 a.m. to 12 p.m.

Not one person showed up.

The turnout was not surprising, according to the vaccination site leader and nurses at the mobile clinic. Last month, new vaccinations across Connecticut fell to the lowest numbers since January, a predictable outcome when nearly 65% of the total state population has received at least one vaccine dose. But in Waterbury, only 46% of residents are fully vaccinated against the coronavirus.

Waterbury is not alone. The populations of fully vaccinated residents in Hartford, New Britain, Bridgeport, and New Haven are between 41% and 51%. These five cities share some similarities: a population that is at least 60% minority, a median household income below $47,000 a year, and a rank within the top 10 cities and towns with the highest cases and deaths from COVID-19, according to data from the state Department of Public Health and the U.S. Census Bureau.

Distribution Disparities

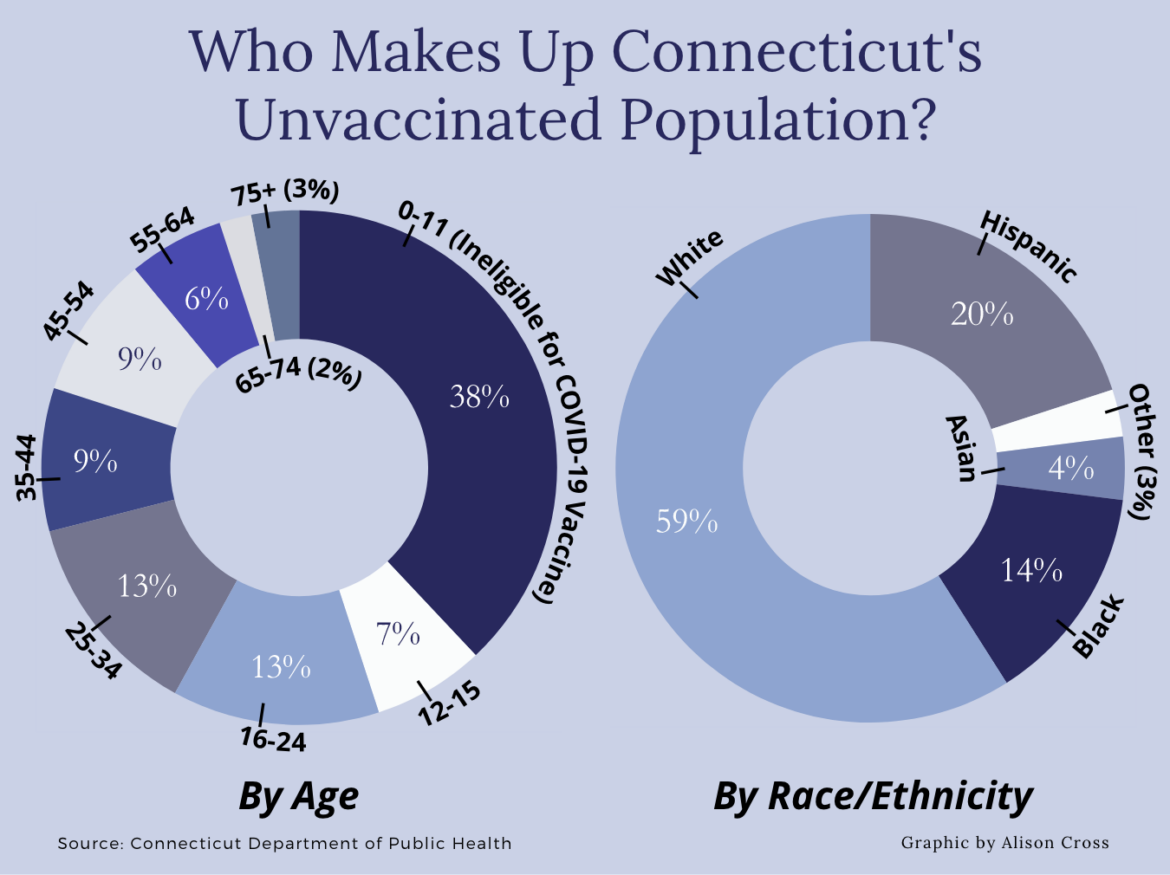

While differences in political ideologies have framed much of the vaccine conversation, the data shows that in Connecticut, the populations with the lowest vaccination rates are racial and ethnic minorities.

According to the DPH, 63% of whites and 65% of Asian/Pacific Islanders have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared to 52% of Native Americans, 52% of Hispanics, 43% of Blacks, and only 33% of multiracial residents in the state.

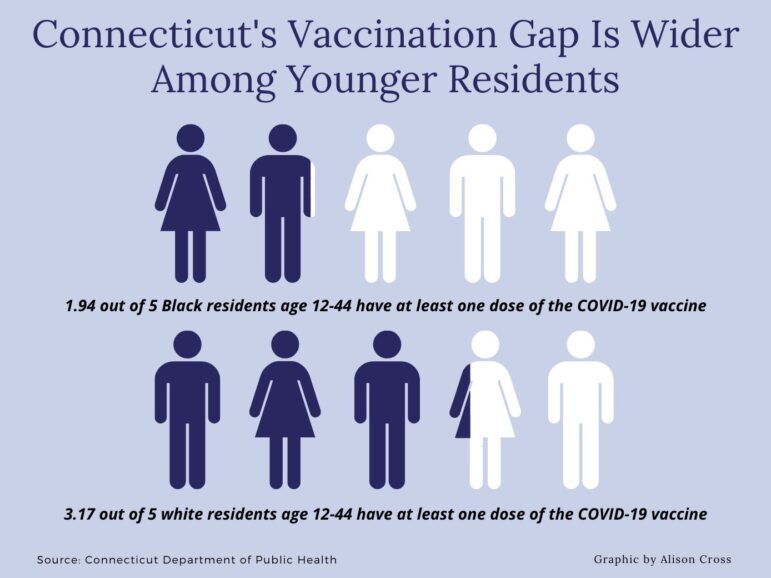

This racial vaccination gap widens among younger demographics. Blacks have a higher percentage of unvaccinated 12- to 34-year-olds than any other racial or ethnic minority in the state. Only 36% of Black residents in this age group have gotten at least one vaccine dose, compared to 62% of whites the same age, according to DPH data.

Dr. Cato T. Laurencin of UConn Health serves as the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. He was among the first to identify and publish a study on disproportionate rates of COVID-19-related infections and deaths among Blacks. Laurencin said that fear of side effects, misinformation, the scarcity of Black medical professionals and a lack of trust in the health care community has contributed to the high rate of vaccine hesitancy within Connecticut’s Black community.

Laurencin said he met with leaders at Facebook to discuss COVID-19 misinformation campaigns specifically targeted to Black social media users. One myth, which started during the nascent stages of the pandemic in Wuhan, stated that Black people were immune to the coronavirus. Laurencin feels this misinformation campaign had particular staying power and partially contributed to the belief shared by many Black individuals that they do not need to get vaccinated because their immune system will be strong enough to fight off the virus.

Laurencin said that the majority of unvaccinated Blacks have medical concerns about the vaccine and that they are carefully weighing the risks and benefits of vaccination with each piece of information they receive.

Laurencin hopes that full FDA approval of the Pfizer vaccine will allay fears within the Black community. However, Laurencin said that if the state truly wants to motivate its Black population, Connecticut must bring Black physicians, nurses and health professionals into the vaccination discussion.

“There’s a large group of Blacks, about 40%, who are not against getting vaccinated and in fact think at some point they will, but need more time and need more information. Blacks who are not getting the COVID-19 vaccine are in a group of individuals that under the proper circumstances, and with the proper discussion, I believe would, at least in Connecticut, be amenable.”

— Dr. Cato T. Laurencin

According to a survey by NRC Health, 40% of Blacks in Connecticut said that they will get the COVID-19 vaccine, but will wait to do so. An additional 10% said they were unsure. Only 9% said they would never get the vaccine, compared to 14% of Hispanics and 17% of Asians.

Laurencin noted that the proportion of Connecticut Blacks who want to wait to get vaccinated is much larger than in other states. For example, NRC Health found that in New York and Massachusetts, only 16% of Black residents said they were waiting to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

“If you look across the country at the trend that’s taking place in terms of vaccine hesitancy, there is something unique going on in Connecticut with the Black community,” Laurencin said. “It’s the largest number I’ve seen, scanning across the other states, 40% who are waiting to get the vaccine. And I think that reflects a sophistication. I think people have been thinking about this, they need to hear from more trusted voices, and I think if they do, they will respond and proceed with the vaccine.”

Laurencin said that Connecticut is in a pivotal position to fight racial disparities in vaccine distribution and that discussion with the Black community will be key.

“If we can’t address the issue of vaccination disparities in Connecticut, it’s going to be very difficult to do it elsewhere,” Laurencin said. “What we’re finding is we need more than education to take place, we need to have a discussion to take place… There’s a tremendous opportunity right now if the state of Connecticut decides to do the right thing and really enlist the trusted voices that can work with the Black community to make it happen.”

Delta Variant Fears

The second half of July saw a resurgence in COVID-19 infections as the Delta variant took hold in Connecticut. Between July 1 and Aug. 4, residents under age 40 made up nearly 65% of all new COVID-19 cases in Connecticut, according to data reported by the state DPH.

Across all races and ethnicities, Connecticut’s younger population is less likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine; 35% of residents age 12-44 are unvaccinated, compared to just 15% of residents older than 45, according to the DPH.

The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected minorities in Connecticut. Data collected by DPH found that while 6% of Connecticut’s white population contracted the disease, 8% of Blacks and 14% of Hispanics became sick with COVID. Ten percent of Hispanics infected with the disease died, compared to 3% of Blacks and 4% of whites.

The population experiencing the greatest rise in new cases in proportion to their population is the Black community. Between July and August, the cases per 100,000 Black individuals increased by more than 1,300, compared to the white case rate, which increased by 970, according to data from DPH.

The population experiencing the greatest rise in new cases in proportion to their population is the Black community. Between July and August, the cases per 100,000 Black individuals increased by more than 1,300, compared to the white case rate, which increased by 970, according to data from DPH.

The lowest-vaccinated cities of Hartford, New Britain, Bridgeport, Waterbury and New Haven, which were among the hardest hit by COVID-19, now rank among the top 10 cities with the highest increase in COVID cases since July.

The city with the highest case rate and total deaths during the pandemic? Waterbury.

Vaccinating Waterbury

“The influx of a disease like COVID, it pulls the rug out from under you … It hits a community like ours particularly hard because folks are stretched pretty thin,” Waterbury Public Health Director Aisling McGuckin said. “I think [Waterbury]’s sort of a perfect storm of populations that are at risk or who may quickly become at risk if circumstances change.”

Within the last three weeks McGuckin said that the city has seen a “tremendous” influx of vaccinations as fears of the Delta variant grow.

“It’s hitting a little closer to home than it has up until this point,” McGuckin said. “Knowing people who are getting sick despite being vaccinated, knowing people who are getting sick who haven’t gotten vaccinated and getting sick very quickly and very intensely, I think that’s impressing on those who haven’t been vaccinated that maybe now’s the time.”

Since the start of the pandemic, Waterbury has reported more than 17,000 COVID cases and 400 deaths as of Aug. 8, according to the Waterbury DPH. An estimated 16% of the city’s population contracted the disease. Now, less than 51% of Waterbury’s population has received at least one vaccine dose.

The “Brass City” is the fifth-largest in the state, with a population just above 107,500, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The racial/ethnic makeup is 38% white, 37% Hispanic, 22% Black, 2% Asian and less than 1% Native American. The median household income is just above $42,000 a year. Twenty percent of Waterbury’s adults over age 25 never graduated from high school, and more than 23% of residents live in poverty.

McGuckin said that much of the city’s vaccination efforts have focused on targeting the most vulnerable populations. She said that partnerships with cultural centers and churches have strengthened communication and deepened trust within the community.

“We benefited from having existing partners upon which we could rely for those inroads into communities that are highest on the social vulnerability index. We’ve had partners at Madre Latina, the Hispanic Coalition, the Greater Waterbury Health Partnership, the Grace Baptist Church and others, who have supplied us with trusted messengers to get out into census tracts where we know that there are young people and people of color who are historically, and with COVID, disproportionately impacted by poor health outcomes,” McGuckin said.

These partnership efforts include door-to-door canvassing in hard-hit neighborhoods to provide education, information and free transportation to and from vaccination centers. McGuckin explained that the public health department placed vaccination clinics in locations that would generate a lot of foot traffic: within government buildings and next to popular shopping areas. The department also brought pop-up vaccination tents to fairs, festivals and other community events that attract young people.

“We’re making ourselves available in the community to ensure that [vaccinations] happen,” McGuckin said. “When people are ready and they are comfortable with the vaccine, we’re here and ready to help them get it and make it as easy as possible.”

“This is a collective responsibility moment in our history, and there’s not going to be many of these. But this is your chance to do your part as a citizen and protect children in your community who can’t get vaccinated, [and] protect immunocompromised folks in your community who can’t get vaccinated,” McGuckin said. “You have the opportunity to help people in that very tangible way, just by getting vaccinated yourself.”