Kimarra Thorbourne planned to restrict added sugar in her babies’ diet as long as possible, but the Windsor mother recently started giving her 7-month-old twins “Motts for Tots” juice “to introduce them to something new.” At their 6-month checkup, the babies’ pediatrician said nothing about avoiding fruit juice or sugar.

But research shows that the food and beverages babies and toddlers consume influences their taste preferences and eating habits throughout life.

For babies, human milk, formula and water are all they need to drink for the first year, pediatricians say.

Dr. Michelle Van Name, a pediatric endocrinologist with Yale Medicine, tells her patients that cow’s milk is the recommendation for toddlers—and it’s less expensive than juices. She said toddlers should be introduced to water at an early age so they develop a taste for it because if they get used to sweet drinks, they won’t like water.

iStock Photo.

The new guidelines say that human milk, formula and water are all babies need to drink for the first year.

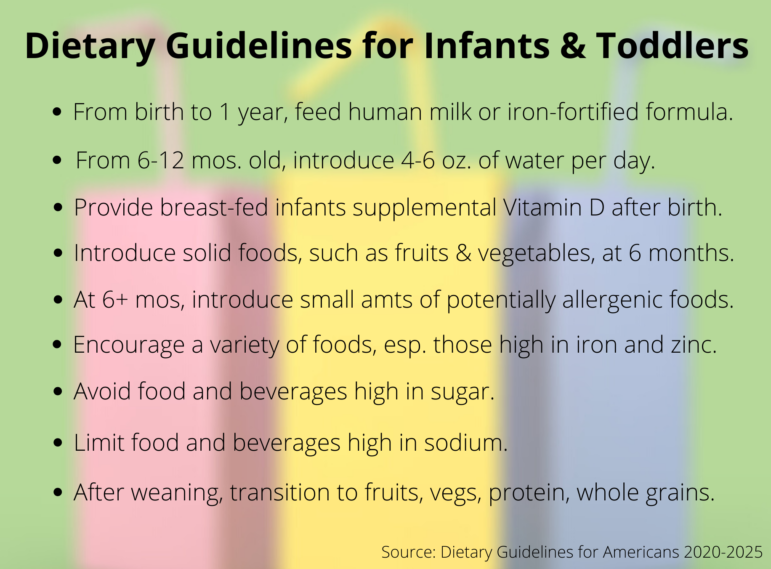

Now, for the first time, parents can find such research-based nutrition guidelines for babies and toddlers in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, produced by the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services.

According to the new federal guidelines, once babies start eating solids at about 6 months, they can have water with their meals to develop a taste for it. After age 1, all children need to drink for healthy development is water and cow’s milk, the guidelines recommend. To reduce the chance of childhood obesity, the guidelines advise avoiding fruit juice or food with added sugar before age 1 and eating fruit rather than drinking fruit juice after 1. Children under 2 should avoid added sugars, including beverages sold as “toddler milks” and “toddler drinks,” the guidelines say.

Marlene Schwartz, director of UConn’s Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity, said the federal dietary guidelines for birth to 2 years affirmed the center’s position that all that is needed is human milk, milk and water.

Marlene Schwartz

“One of the big controversies in the field right now is ‘toddler milks’ and ‘toddler drinks,’” Schwartz said. “The Rudd Center has done a lot of research, and we think they’re unnecessary. They’re being marketed in a very deceptive way,” she said. (The labels, written in English and Spanish, include wording suggesting the product supports brain development and immune systems.)

Growing childhood obesity rates drove many of the new recommendations: 14% of 2- to 5-year-olds have obesity; 18% of 6- to 11-year-olds have obesity; and 21% of 12- to 19-year-olds have obesity, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported in 2019. Among those 2 to 19, obesity prevalence reached 26% of Hispanics and 22% of Blacks, while 14% of whites and 11% of Asians, respectively, were obese, reports the CDC.

Schwartz would have preferred seeing the guidelines recommend avoiding even 100% fruit juice in the first two years of life, rather than saying that up to 4 ounces of 100% juice could be included in a healthy diet after age 1.

“I don’t love that,” she said. “It sounds like you should give your kids 100% juice.” Rudd Center-conducted studies found many parents thought some sugary drinks were healthy options because of how they’re marketed, she said.

It’s not the parents’ fault, she said. In the United States, food, beverage and restaurant companies spend nearly $14 billion per year on advertising, and more than 80% of the advertising promotes fast food, sugary drinks, candy and unhealthy snacks, according to the Rudd Center. This overshadows the $1 billion budget for all chronic disease prevention and health promotion produced by the CDC, the Rudd Center found.

“I would have liked to see a stronger statement [in the guidelines] about providing small amounts of plain water when introducing food. And be more explicit: Water should be the beverage of choice,” Schwartz said. The guidelines state that after 12 months, toddlers only need milk and water, a clarity she appreciated.

With more mothers breastfeeding, infant formula sales have decreased, “so the formula companies had to create a new product to sell,” Schwartz said. “We’ve been very vocally critical of these products. These take advantage of young mothers.”

Bonnie Phillips Graphic.

Yale’s Van Name agreed, adding, “Kids do not need juice. It’s more nutritious to eat a piece of fruit than drink it as juice.” Juice “could contribute to excess calorie consumption,” she said.

Alia Reynolds wasn’t exposed to added sugar until she was 4, so she’s planning to keep processed sugar out of her baby’s diet for as long as possible. Based on her reading, the West Hartford mother says she has not given her 10-month-old daughter, Vivienne, any juice and doesn’t plan to. Vivienne drinks water from a straw with her meals, which Reynolds started giving her at about 6 months, again based on her reading.

Schwartz, who has been studying obesity for 15 years, said water needs to be the default beverage from the start. When elementary-school-aged children are overweight and pediatricians advise them to stop drinking juice and soda, parents say their kids don’t like water, she said.

Van Name also recommends children avoid sports drinks, which were designed for elite athletes. Children playing on local soccer and basketball teams do not need anything but water, she said.

“It’s important to start early on,” Van Name said. “Most of what we recommend is eat real food.”