Melanie Stengel Photo.

Jay Katz, administrator, Leeway nursing facility in New Haven.

The coronavirus has decimated many of the nation’s nursing homes, where elderly, chronically ill residents account for 64% of Connecticut’s death toll of 4,201 and rising. They are roughly 100 times more likely to die of the virus than other people in the state.

So, the fact that some 41 of Connecticut’s 214 nursing homes have managed to keep out the virus, according to an analysis by C-HIT, is both remarkable and mystifying. Did they just get lucky?

Administrators at several COVID-19-free facilities use the word “fortunate” to describe a situation they acknowledge could change at any time.

“It’s really a day-by-day effort,” said Sue Peglow, administrator at the 120-bed Pendleton Health & Rehabilitation Center in Mystic, who said she supervises an “excellent staff” of 200. Early in the pandemic, residents who exhibited possible symptoms of the virus were isolated until test results showed they were not infected. After Gov. Ned Lamont prohibited most visitors to nursing homes, Pendleton kept in regular contact with residents’ families and has relied on telehealth appointments using video chats to reduce visits by outside medical providers. Their food suppliers leave deliveries at the back door instead of entering the building. And restaurant take-out orders are banned.

In her 28 years at Pendleton, Peglow has faced many challenges, she said, but none come close to matching COVID-19. “It’s ongoing and all-consuming.”

Leeway, Inc. in New Haven has also kept residents COVID-19 free, and Executive Director Jay Katz isn’t exactly sure why. But he does have some theories.

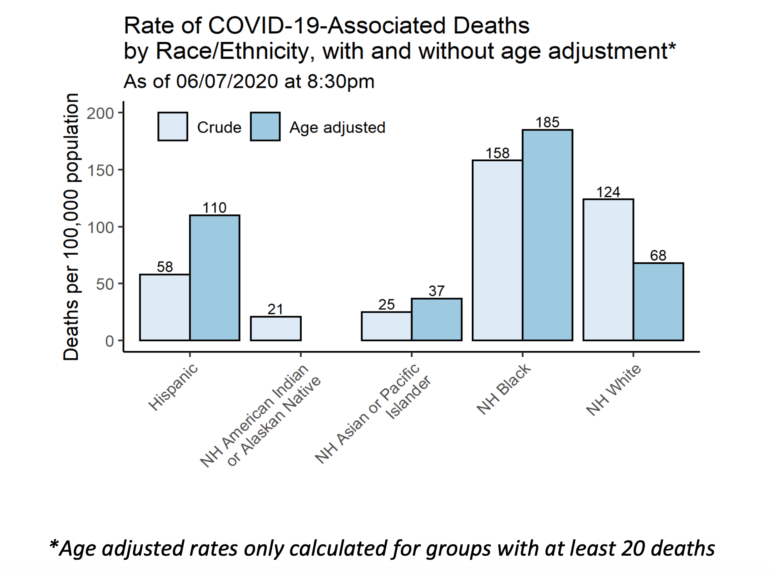

“We’re very fortunate that we’re so small, and our staff is great,” he said. Leeway has only 30 beds and currently 29 residents, predominantly black. In Connecticut, the virus has hit communities of color particularly hard, and living in a nursing home heightens that risk. Some nursing homes with the most deaths from COVID-19 as of June 10 also have higher percentages of minorities, according to a C-HIT review of state data.

Because of its size, Katz said, Leeway has limited interaction with the community and outside contractors, compared to a larger facility with more staff members and service providers going in and out.

Because of its size, Katz said, Leeway has limited interaction with the community and outside contractors, compared to a larger facility with more staff members and service providers going in and out.

Ironically, the facility may have benefited from a flu outbreak earlier this year, he said. Visitors have not been allowed since January. Leeway’s medical director also points out that residents each have their own room, which minimizes their potential exposure to the virus.

At the 44-bed Twin Maples Health Care Facility in Durham, administrator Amy Bentley said that getting an early start made a difference in fighting the virus. When there were conflicting or confusing recommendations at the beginning of the pandemic about how to protect residents and staff, the home didn’t hesitate.

“Our facility was very fast in our implementation of all measures,” she said, including ensuring that supplies and equipment were always available. “Twin Maples practiced under the belief that we were and/or could be affected by this virus at any time.” Just last week, one resident who displayed no symptoms tested positive for COVID-19, becoming the facility’s first case.

On June 8, Gov. Lamont ordered an independent review of how nursing homes and assisted living centers prepared for and responded to COVID-19 to find out why some were hit so hard. He wants answers before a possible second wave of the virus arrives in the fall.

On the same day, Deidre Gifford, acting commissioner of the Department of Public Health, issued another round of recommendations for facilities to test residents and isolate those who are infected, and strengthen infection control programs. Her memo also reminds nursing home administrators that the governor’s executive order requires weekly staff testing starting no later than June 14, and that, under federal guidance, previously negative residents should be re-tested until no new cases of COVID-19 are identified for 14 days.

While it’s still too soon to explain why some homes have fared better than others, one factor has emerged, said Matt Barrett, president and chief executive officer of the Connecticut Association of Health Care Facilities.

“If a facility is located in a highly populated area with a high prevalence of the virus in that community, research has shown there is a strong correlation to the COVID presence in that facility,” he said. This “very tricky and mysterious” virus is hidden by asymptomatic carriers—people who have no symptoms but can still infect others—and can enter a nursing home regardless of the facility’s staffing levels or past infection control violations, he said. Residents still contracted the virus in facilities earning high marks for overall performance under Medicare’s star rating system.

Of Connecticut’s COVID-19-free nursing homes rated by Medicare on its Nursing Home Compare website, a C-HIT analysis found 29 earned high overall marks: either four (“above average”) or five (“much above average”) stars, (full list at bottom of story). The homes were graded on staffing levels, quality of resident care, compliance with nursing home regulations, and other factors.

But completely blaming the virus lets nursing homes off the hook, said Toby Edelman, senior policy attorney at the Center for Medicare Advocacy based in Willimantic.

“The industry doesn’t take any responsibility for the fact that they have had inadequate staffing, poor infection control practices for years, and the enforcement system has been overly tolerant of infection control violations,” Edelman said. She noted that in a five-year period ending in 2017, 82% of nursing homes nationally had infection control deficiencies and half had multiple persistent problems, according to a study released last month by the Government Accountability Office, the independent investigative arm of Congress.

Map by Susan Jaffe. Sources: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Connecticut Department of Public Health

In Connecticut, about 67% of the state’s nursing homes were cited for infection-control violations between 2017 and 2019, a C-HIT analysis of federal data found in March. In April, state health inspectors, working with the National Guard, began inspecting all state nursing homes to check infection control procedures.

Inspectors found that even some nursing homes with high numbers of cases or deaths met inspection control procedures. Kimberly Hall North, where 45 residents have died, had no deficiencies during a DPH visit on May 30.

Other homes were cited for violations, including failure to separate COVID-19-positive residents from non-COVID-19 residents, improper use of personal protective equipment, and improper sanitation of equipment. Windsor Health and Rehabilitation Center, with 22 deaths, was recently fined $10,000 by DPH for infection-control violations.

Mairead Painter, the state’s Long-Term Care Ombudsman, who is a consumer advocate for nursing home residents, said the homes in urban areas like Hartford, Waterbury and Bridgeport were most affected by the virus early in the pandemic and “had to figure this out in the dark.” With such a high rate of infected individuals who didn’t appear to be sick, “there was no way they could’ve gotten ahead of this,” said Painter, who continues to hold live Facebook video chats three times a week with residents’ families about the impact of the virus.

Since the early days of the pandemic, DPH has been rolling out new steps for battling the virus, as federal health officials shared more information. Painter praised DPH for being transparent and for new protocols mandating face masks for staff (and residents who can tolerate them), plus “full house” virus testing and isolation of positive cases. But the battle is far from over.

“I think we are at the very beginning of actually understanding the effects of this virus and what happened,” she said. “Until our researchers get to go in and really drill down on these numbers, we’re not going to have a clear picture.”

A list of COVID-19-free nursing homes, as of June 10:

Loading...

Loading...

Contact Susan Jaffe at Jaffe.KHN@gmail.com, @susanjaffe