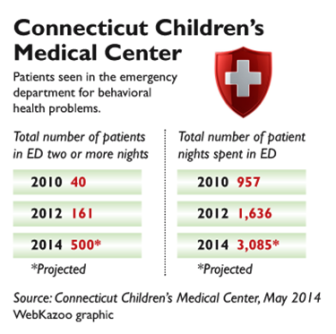

Just a few years ago, it was rare that children with mental health problems would spend two or more nights in the emergency room at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center. Only 40 children stayed that long in 2010.

So far this year, more than 250 children have spent multiple nights in the emergency department (ED) – a number expected to reach 500 by the end of the year.

As policy makers work to finalize a statewide children’s behavioral health plan, a report by the hospital, obtained by C-HIT, projects that children with mental health problems will spend a total of 3,085 nights in the ED – more than triple the number in 2010. The average stay is about 15 hours, with some children remaining in the ED for 10 days or more.

As policy makers work to finalize a statewide children’s behavioral health plan, a report by the hospital, obtained by C-HIT, projects that children with mental health problems will spend a total of 3,085 nights in the ED – more than triple the number in 2010. The average stay is about 15 hours, with some children remaining in the ED for 10 days or more.

Yale-New Haven Hospital also has seen a 10- to 15-percent increase in ED visits this year, as it has in each of the past several years, said Dr. Andres Martin, medical director of children’s psychiatric inpatient services.

Fueling the ED crunch is a shortage of placements for children who need intensive residential care, hospital officials said. They noted that the state Department of Children and Families (DCF) has cut funding for congregate or group homes and is steering children to remain with families — even when community-based support services are lacking, they said.

“The current DCF commissioner has been very opposed to congregate care, and wants to place children in home settings. It’s well-intentioned, but in my opinion, the pendulum has swung too far,” Martin said. He said some children bounce back to the ED “five or six times” in a year because their families cannot cope with their problems.

“We do struggle with some kids for whom we just don’t have an appropriate placement,” Martin said. In other cases, placements are found, but the state will not authorize care.

While Yale has its own pediatric psychiatric units – 36 beds for children ages 15 and under – CCMC does not. About 40 percent of CCMC’s emergency cases are referred to the Institute of Living’s six-bed “CARES” unit, opened in 2007 to alleviate ED overcrowding, or another small inpatient unit; the rest go home or “we struggle to find placements,” said Theresa Hendricksen, executive vice president and chief operating officer of CCMC.

She said the numbers of multi-night stays in the ED have risen largely because “it takes longer for a patient to be discharged when there is no place for them to go.”

A DCF official, Kristina Stevens, said the spike in longer ED stays is not related to the closing of group homes or a shortage of treatment programs, but instead mirrors a national trend driven by myriad factors. Stevens, DCF’s administrator for clinical and community consultation and support, said the statewide average length of stay for children with psychiatric problems has remained relatively consistent, at 1.5 days.

Still, she acknowledged, “It was a big spike this year . . . Nobody wants children sitting in the ED and not getting the services they need, “ she said. “We’re doing a deep dive into the numbers to see who this population is” and how they might be diverted to other services.

Still, she acknowledged, “It was a big spike this year . . . Nobody wants children sitting in the ED and not getting the services they need, “ she said. “We’re doing a deep dive into the numbers to see who this population is” and how they might be diverted to other services.

At CCMC, Hendricksen said the multiple-night stays are tough on both kids and staff.

“It’s awful. In a lot of cases, we’re talking about kids in a room with a mattress and someone just watching them, for days,” she said. “Other than keeping them safe, we’re not helping them get better. We don’t provide therapy — we provide stripped-down services. It’s hard on them, and it’s tough on our pediatric nurses.”

In May, the ED at the children’s hospital saw 367 children in mental health crisis – an all-time high, Hendricksen said. At one point, 21 of the 24 ED bays were filled with children in mental health crisis, while other patients with medical problems waited to be seen. The hospital adds staff to keep up with the volume, and is expanding its ED to add bays for psychiatric patients, she said.

The multi-day stays are mainly due to delays in finding treatment slots, Hendricksen said; “There are acute shortages of inpatient and outpatient programs.” Many inpatient programs also report a discharge backlog because of a lack of community-based options.

Both Hendricksen and Martin said ED visits climb during the school year, when school officials refer problem children, and then subside during the summer. At Yale-New Haven this school year, “We were bursting at the seams,” Martin said.

Greater awareness about children’s mental health and a “zero tolerance” policy in schools, especially after the Newtown school shootings, has contributed to the increase, they and others said.

As the hospitals grapple with the ED backlog, DCF is closing five group homes and reducing inpatient slots in other programs, including the Village for Families and Children in Hartford, which is losing funding for the residential component of its Intensive Community Program, touted as a model by DCF when it was launched in 2012.

Under DCF Commissioner Joette Katz, the agency has set as goals reducing the length of stay in residential treatment centers and dramatically limiting the number of children ages 12 and under who are served in non-family settings.

Stevens, of DCF, said the shift in Connecticut reflects a national move away from institutional care to family settings. But critics say the state does not have enough community services in place – yet — to support the policy shift to home-based care.

The five group homes that will close in August are located in Bridgeport, Bethlehem, Torrington and Lebanon, with a total of 27 beds.

DCF in October will present a statewide plan for improving behavioral health services to children, under legislation passed in 2013, after the Newtown shootings. Among ideas that have been proposed is an expansion of a statewide Emergency Mobile Psychiatric Services (EMPS) program, which has helped to divert ED calls from schools and families. Both CCMC and Yale-New Haven are working with EMPS to assess children and direct families to care.

Encouraging providers to add more inpatient psychiatric beds for children could be difficult because Medicaid reimbursement rates are low, advocates said.

Nationally, pediatric psychiatric ED visits increased from an estimated 491,000 in 2001 to 619,000 in 2010, according to a recent report in the journal Academic Emergency Medicine. Teenagers and publicly insured patients were at increased risk of landing in the ED.

For now, Hendricksen and other hospital officials brace for another wave of emergency room visits in September.

“We keep saying, ‘We hit 200 this month – it can’t get worse,’” Henricksen said. “And then it hits 250. And then 300 . . .

“We ask ourselves all the time, how much higher can it go?”