Task Force To Examine So-Called ‘Custody For Care’ Controversy

|

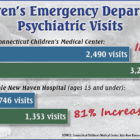

A task force created by state lawmakers will examine whether the Department of Children and Families (DCF) should be prohibited from requiring that parents give up custody of their children in order to access mental health and other services, under legislation signed by the governor. The newly formed panel, which is charged with reporting its recommendations by Feb. 1, 2018, will study whether state statutes should be amended to prohibit DCF from requiring or requesting that a parent or guardian of a youth admitted to DCF on a voluntary basis terminate his or parental rights or transfer custody in order to obtain services. The task force also will study ways of increasing families’ access to voluntary services without making parents relinquish custody of their children. The legislation creating the task force was prompted by recent stories by C-HIT that detailed a practice known as ‘trading custody for care,’ in which parents who cannot meet their children’s severe behavioral health needs in a home setting are subject to “uncared for” petitions that turn their children over to DCF custody.