In theory, a do-it-yourself rape kit, where a victim of rape or sexual assault collects evidence in the privacy of his or her home, seems like a good idea.

![]() Going to the police or a hospital after a rape is immeasurably difficult for some. There’s a stigma, and victims may fear mistreatment at the hands of law enforcement or hospital personnel.

Going to the police or a hospital after a rape is immeasurably difficult for some. There’s a stigma, and victims may fear mistreatment at the hands of law enforcement or hospital personnel.

But advocates and others say newly introduced home rape kits are roughly as useless as the boxes they come in. There’s no guarantee self-collected evidence is admissible in court, and the kits aren’t nearly as comprehensive as those offered by the state.

In fact, earlier this month, Connecticut’s Attorney General, William Tong, joined other attorneys general and sent letters to two DIY rape kit companies, MeToo, which is based in Brooklyn, and New Jersey-based PRESERVEkit, to determine if the organizations violated Connecticut Unfair Trade Practices Act. That law, which was adopted nearly 50 years ago, could determine whether the kits can be sold in Connecticut. The companies have until Oct. 21 to answer questions about their products.

“We take this matter extremely seriously,” Tong said in a press release. “Efforts to profit off survivors’ trauma do a grave disservice to us all.”

In fact, commodifying others’ trauma and fear is big business—or it can be.

The MeToo kit isn’t yet on the market. A co-founder of PRESERVEkit, which was available on Amazon for $29.95 but has since been removed, insists on the company’s website that her organization never claimed evidence collected with their kit would be admissible in court. Nor does PRESERVEkit seek to replace nurses or doctors who are specially trained in evidence collection, she said.

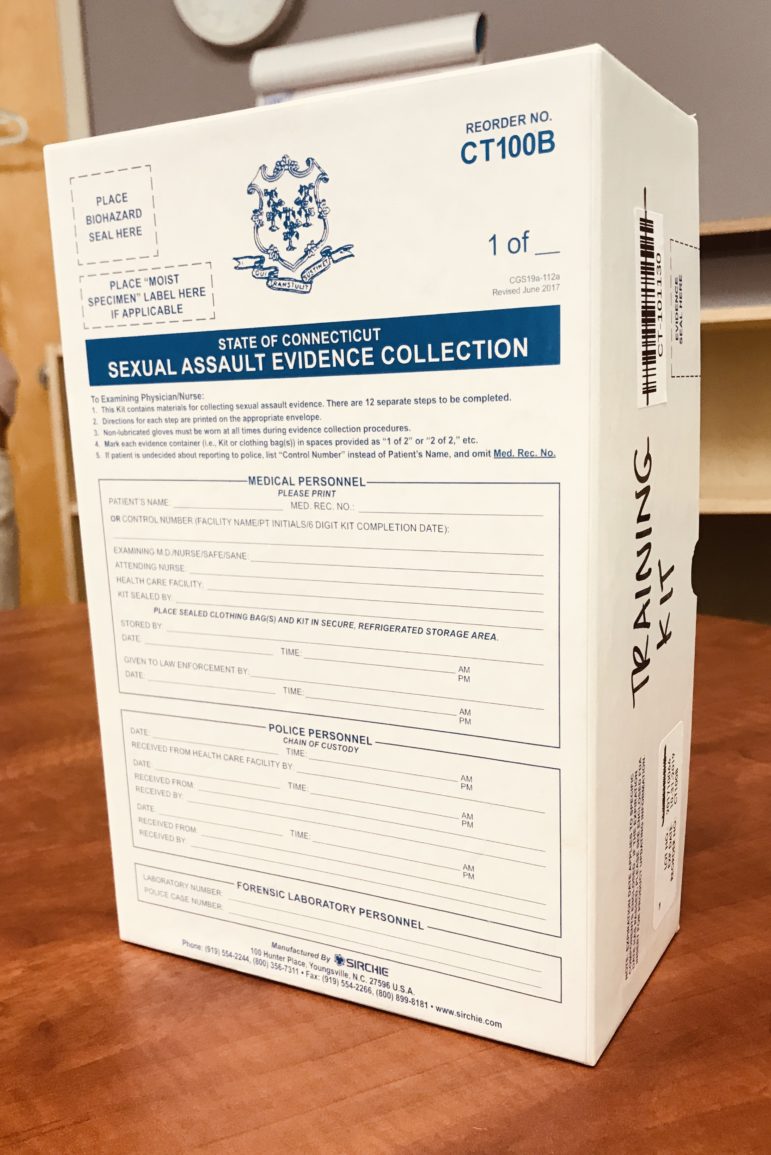

CT sexual assault evidence collection kit.

Rape kits provided free by the state involve a 12-step regimen that includes a detailed description of the event; a special mat the victim stands on to remove clothing, which is ultimately bagged and used for evidence; multiple swabs and a comb to collect pubic hairs for evidence, said Asia Nhatavong, justice involved advocacy coordinator at Connecticut Alliance to End Sexual Violence. Before evidence is collected, the victim must give consent. In fact, the victim gives consent (or not) at each step, said Nhatavong. And the specially trained doctor or nurse who collects the evidence does not leave the room until the exam is completed.

In addition, an advocate stays with the victim through the entire process, which can last five hours. Collecting evidence in private cuts the victim off from much-needed support and services.

“Victims are isolated already,” said Lucy Nolan, the Alliance’s director of policy and public relations. When a person comes in for a rape kit, advocates and others can help them with other resources, said Nhatavong.

By comparison, the DIY kits generally include two steps: swabs and spit tests.

The last time rape kits made the news in Connecticut was 2015. There was a shameful backlog of nearly 1,200 kits that had not been tested scattered around the state. That same year, legislators passed and then-Gov. Dannel P. Malloy signed a law that requires rape kits be sent to the state crime lab within 10 days of collection, and tested within two months. (Victims have five days after the assault to be tested with a rape kit.)

The result of that law is that now the state essentially has no backlog, said Nolan. And the rape kits the state uses are stamped with a barcode, said Nhatavong. That way the kits can be tracked.

In the DIY advertising, home rape kit companies say that their products are designed for the 77% of rape and sexual assault victims who do not report the crime to the authorities. The designer of the MeToo kit has even said that having a home kit on hand could serve as a deterrent against rape.

Nolan says no and points to the shoebox-sized state rape kit on a table in front of her.

“Look at this,” she said. “This is what we know can work in courts.”

If you have been sexually assaulted call the statewide sexual assault hotline at: 1-888-999-5545. For more information click here.

Susan Campbell is a distinguished lecturer at the University of New Haven. She can be reached at slcampbell417@gmail.com.