It’s a summer afternoon and parents with their young children have gathered to hear what a nutritionist with Women, Infants and Children (WIC) has to offer.

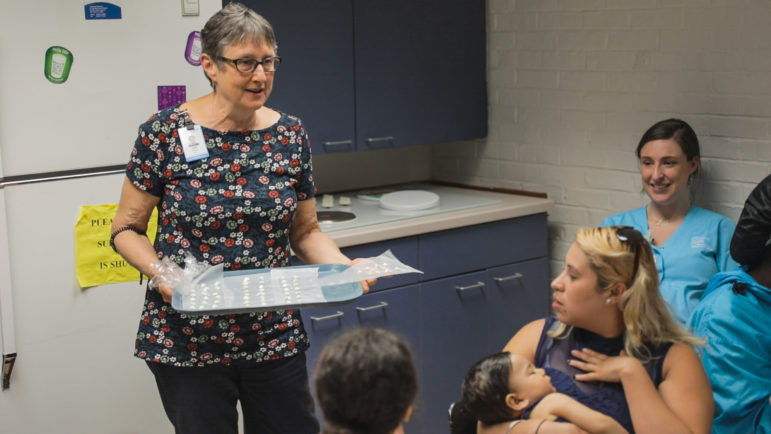

They watch with intrigue as Mary Paige demonstrates how to make yogurt dots from frozen Greek yogurt and French fries from roasted parsnips and carrots.

After a 10-minute demo in the WIC office at Yale New Haven Hospital’s Primary Care Center, Stephany Uriostegui of West Haven is sold. She can’t wait to try the recipes at home for her 10-month-old son and 5- and 7-year-old daughters.

“I always buy the [yogurt dots] from Walmart,” she said. “If I can make them myself, even better. And these will be good for teething.”

The five parents who attended the demo are participants in a pilot program that aims to combat childhood obesity. Launched last fall, the program integrates a healthy-eating curriculum into group well-child visits at the Primary Care Center. Leaders expect it to result in slower weight gain among infants as well as healthier mothers and families.

Introducing nutrition and a healthful mindset to new parents from the outset is crucial, said project leader Dr. Marjorie Rosenthal, associate professor of pediatrics and director of education at the Center for Research and Engagement at Yale University School of Medicine.

“Obesity is a big problem in our country,” she said. “It is such an issue of health disparity. The numbers are really far worse among people who are living in poverty. Healthy food is expensive, and food that is much more likely to lead to obesity is cheap and easy.”

That’s why the program is partnering with the WIC office, she said. WIC is the federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program that provides subsidies to low-income pregnant and postpartum women and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk.

In 2014, 9.5 percent of WIC-enrolled children in Connecticut between the ages of 3 months and 23 months had high weight for their length, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Racial disparities were evident, with a 10.6 percent obesity rate among Hispanic children in that age group, compared with 9.9 percent among blacks and 7.7 percent among whites.

Also in 2014, 15.3 percent of Connecticut WIC participants aged 2 to 4 were obese, according to the CDC. In that age group, 18.2 percent of Hispanics were obese, compared with 12.4 percent of blacks and 12.1 percent of whites. But the obesity rate among 2- to 4-year-olds marked a decrease from recent years, down from 17.1 percent in 2010.

Nationally, obesity rates declined among 2- to 4-year-olds, from 15.9 percent in 2010 to 14.5 percent in 2014, data show. Obesity rates fell in 31 states, including Connecticut.

In the Yale program, parents opt to participate in well-child visits as a group. The children are weighed, measured and vaccinated, Rosenthal said, and parents have access to a pediatrician.

Carl Jordan Castro Photo.

Mary Paige discusses healthy food choices with Stephany Uriostegui and other parents.

The nutrition component, including cooking demonstrations, is added at well visits, when babies are 3 months, 6 months, 9 months and 1 year old.

“This model is extremely unique,” said Deborah Diehl, manager of the WIC program at the hospital. “Nobody is really doing this in the whole state. Having the nutrition component is critical.”

“One of the goals is to empower families, especially because we’re dealing with people who often feel disempowered in other aspects of their lives,” Rosenthal said. “Thinking about [how to care for your child] and relating that to food made a lot of sense to us.”

When babies are 3 months old, for instance, the group focuses on how parents can eat well to be role models to their children, Paige said. When babies are 6 months, parents learn how to make homemade baby food; and when babies are 9 months old, parents learn how to know when babies are full or hungry, Paige said.

At a recent session for parents of 9-month-olds, the adults—mostly mothers but also a couple of fathers—learned how to introduce peanut butter to their babies by thinning it out with warm water to make it more palatable. They also learned how to read nutrition labels.

Yale’s Primary Care Center, which houses the WIC office, has offered group well-child visits for a decade but the focus on nutrition within the groups is new, Rosenthal said. The center serves only people who are on Medicaid or HUSKY, she said.

For Uriostegui, the process has been eye-opening. “It’s benefiting all of us,” she said. “Today I just learned a new vegetable [parsnip] I never heard of before. I’m gonna try it. We’re learning new ways to introduce babies to new foods.”

The pilot program is one of three initiatives statewide that recently received grants funded by the Children’s Fund of Connecticut, the Connecticut Health Foundation and Newman’s Own Foundation and administered by the Child Health and Development Institute.

In addition to Yale’s program, the University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity received $64,998 to study barriers to participation in the federal Child and Adult Care Food Program, and UConn’s Allied Health Sciences received $64,982 to develop a program for communicating with low-income parents in East Hartford about best practices for feeding toddlers.