As one of the wealthiest towns in the state, Darien has few residents who routinely go hungry. It’s also ranked in the bottom quartile of Connecticut when it comes to services for residents who may forgo a meal, according to a recent food accessibility survey.

With a median household income of $181,521, it ranked second in the state for “food security” – defined as ready access to affordable, nutritious food. It does not take part in the national school lunch or breakfast programs because town officials don’t see a need. But there are 145 residents enrolled in the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP).

“No demand, no program. It’s logic,” said David Knauf, the health director of Darien. “We are not going to provide a service that nobody needs.”

But that sentiment concerns Adam Rabinowitz and Jill Martin of The Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy and the cooperative extension program, both at the University of Connecticut.

They recently published a study examining the accessibility and affordability of food for Connecticut residents — and the availability of programs that help people in need.

“If you have at least one family that needs assistance, why not?’’ asks Martin. “The federal government will reimburse you, and you should make sure that all people who are eligible are getting these benefits.”

Darien, along with most towns in Fairfield County, shoreline towns such as Madison, and many outer suburbs of Hartford, including Glastonbury, ranked high in terms of food security in the study because most of their residents were always able to afford and access enough food.

On the other hand, cities such as Hartford, New Haven and New Britain ranked well in terms of food assistance because their governments provide citizens with several programs, such as the federally funded school meals and bus transportation to grocery stores.

After all the data was collected and analyzed, no town is at the top of both lists.

“If their ranking is low on food assistance, then even in a town…that ranks well for food security, there probably isn’t a recognition that there are people who need food assistance,” Martin said.

But Simsbury, which ranks tenth for food security and 162nd for food assistance, is trying to do just that.

Although relatively well off, Simsbury has 495 residents who are receiving SNAP, and 6.7 percent of its school children are eligible for the school lunch and breakfast programs.

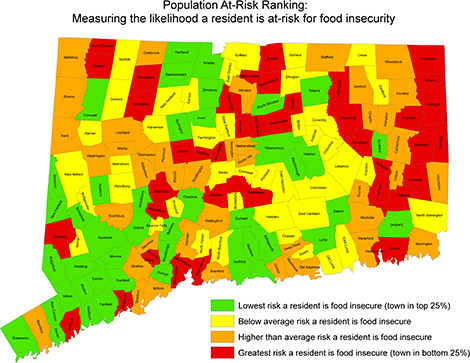

Zwick Center Graphic

There are many more residents who are eligible for these programs than are utilizing them.

“We are encouraging people to apply for SNAP,” Mickey Lecours-Beck, the director of social services in Simsbury, said. “We have volunteers that go around and pick up the applications to make it easier for people.”

Over the past several years, private organizations have recognized the problem of food insecurity in the town and have stepped up to help citizens.

“Gift of Love, a nonprofit organization, sends a weekend backpack full of food home with children that apply,” Lecours-Beck said.

In many communities, especially the more affluent, private organizations such as Gift of Love are the only way a family may get any food assistance.

“There is a lot of public and political will involved in food assistance,” Martin said. “It takes political will to get the school lunch program offered.”

To Martin, it makes sense that cities such as Hartford and New Haven, which rank 169 and 168 in terms of food security, are doing a great job with government-run programs such as the national school lunch program. “It is not surprising that New Haven and Hartford are where they are, because they have a lot of political will,” Martin said.

Smaller cities, such as Norwich, may not have as much political will as the state capitol, but the many non-profit organizations and the UNCAS Health District are working to help the more than 14 percent of the city’s population that lives at or below the federal poverty level, according to a January 2013 report by the Connecticut Association for Community Action.

Patrick McCormack, the health director for the UNCAS Health District, said he knows the difficulty of convincing the skeptics of the need for more food assistance programs.

“How you present the argument to people who believe that the poor should be working and providing for themselves is key,” McCormack said. “There is a cost to people not getting enough food that affects us all – emergency room visits and parents staying home from work because they have sick children. These put economic stress and burdens on the whole community.”

Even when programs such as summer meals are in place, or food pantries are available, making sure the food gets to the residents is yet another hurdle.

“This year, there will be 23 open sites for the summer meals in Norwich,” McCormack said. “Going to the location where the people are has helped a lot, although there is a lot more work and an extra cost involved in getting the food out to people in a healthful way.”

Nancy Rossi, the manager for the Gemma E. Moran Food Center for the United Way of Southeastern Connecticut, has also recognized the impediment of traveling to pantries that prevents many of her potential customers from receiving food.

“Last year, we started our mobile food truck,” Rossi said. “We deliver 5,000 pounds of fresh produce and lean protein each month.”

In September, the United Way will be delivering its vegetables, fruit, proteins, rice, pasta, and the occasional canned goods to 12 sites in New London County, three of which are in Norwich, Rossi said.

“Two hundred and twenty-two families come to the Norwich High School site, making it our largest site,” Rossi said.

Thousands of Connecticut residents, including some in wealthy towns, sometimes go hungry. “Wealthier communities have it more manageable than cities like Hartford, where 40 percent of the population is below the poverty line. But despite their resources, they aren’t doing nearly as much to help,” Martin said.

It isn’t about getting people to donate to large national or international organizations to stop world hunger, advocates said.

“Raising awareness and framing it in a way that makes sense to people is important,” McCormack said. “It doesn’t make sense to hear about something that happens somewhere else. Tell them about the poor and hungry in their community.”

To find your town’s ranking click here.

Julia Werth, a C-HIT intern, is a student at the University of Connecticut.